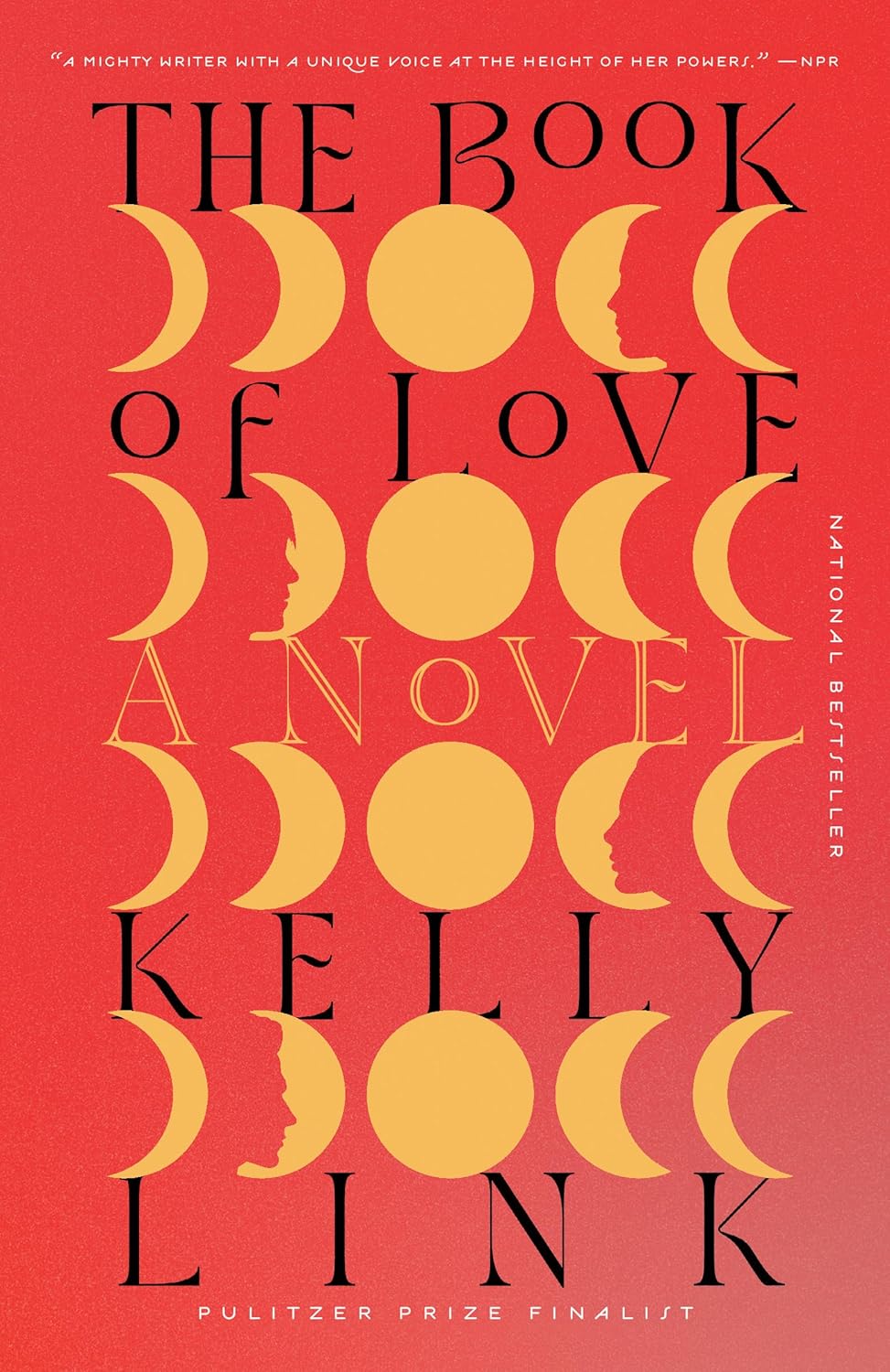

The Book of Love

The Book of Mo 2

by Link, KellyThe chapter opens with Mo returning to his grandmother’s house, feeling emotionally drained and physically hungry after a long absence. The departure of Mr. Anabin’s car marks a moment of solitude for Mo, who longs to rest and perhaps cry, overwhelmed by the harsh realities of bodily needs and emotional pain. Despite his exhaustion, the presence of his grandmother’s legacy and the memories tied to her home create a poignant backdrop for his return, emphasizing the deep connection between family, loss, and the passage of time.

Visitors inspired by Caitlynn Hightower’s romance novels, written under a pseudonym, frequent the town of Lovesend and the local bookstore, drawn by the charm of her signed works and the lavender theme. These readers, particularly young Black women and girls, find solace and encouragement in her stories and her generosity. Caitlynn’s willingness to nurture aspiring writers, offering advice on craft and encouragement, contrasts with Mo’s more cynical view of romance literature, highlighting themes of love, inclusion, and creative mentorship.

The narrative then reveals the harsh realities behind the idyllic image of Caitlynn’s books and her life. Mo reflects on his grandmother’s death and the impermanence of love, likening it to the fleeting freshness of pastries left on her porch, which were routinely discarded. The emotional weight of loss and the practical absence of Mo during his grandmother’s final days deepen his grief, underscoring the complexity of familial love and the loneliness that accompanies it.

The chapter closes with Mo’s encounter with Jenny Ping, his grandmother’s secretary, who has been vigilantly awaiting his return. Their interaction blends concern, humor, and emotional support, as Jenny gently admonishes Mo for his reckless behavior and offers comfort through tea and companionship. This moment highlights the themes of guardianship, resilience, and the tentative steps toward healing after loss, setting a tone of cautious hope amidst sorrow.

FAQs

1. How does Mo’s emotional state at the beginning of the chapter reflect his experience of loss and physical needs?

Answer:

At the start of the chapter, Mo is emotionally drained and physically hungry, highlighting a complex interplay between grief and bodily demands. He is no longer crying but desires to lie down and sleep, which suggests exhaustion from emotional pain. His hunger is a stark reminder of the physical body’s needs, which contrast with his emotional turmoil. This duality emphasizes how grief affects both mind and body, showing that despite deep sadness, basic survival needs persist. The text states, “No sooner did you have a body again than, hooray, you were reminded of the undignified demands the body places upon you,” underscoring the tension between his emotional state and physical reality.2. What role does Caitlynn Hightower’s character and her Lavender Glass books play in the community of Lovesend?

Answer:

Caitlynn Hightower, Mo’s grandmother, is a beloved figure in Lovesend, with her Lavender Glass books fostering a sense of community and connection. Her readers visit the town, the local bookshop, and her home, leaving gifts and seeking her company. She supports young Black women readers and writers, encouraging them to keep writing even when her own books do not fully represent their experiences. This dynamic illustrates her role as a mentor and a bridge between different generations and identities within the literary community. The chapter highlights how her presence and work create a welcoming space, despite the limitations of her romance novels, which sometimes exclude certain voices.3. Analyze the significance of the imagery related to Mo’s grandmother’s house and the items left on the porch. What does this reveal about her character and Mo’s feelings?

Answer:

The imagery of the grandmother’s house and the porch items reveals themes of love, loss, and memory. The baked goods left on the porch, which Maryanne Gorch’s Rule dictates must be discarded, symbolize both care and betrayal—the “treachery” in the Lavender Glass books mirrors the complexities of love and relationships. Mo’s hunger and longing for these simple comforts reflect his deeper yearning for connection and the presence of his grandmother. The mention of parcels of lavender and shortbread on her grave further evokes a poignant blend of remembrance and sorrow, showing Mo’s struggle to reconcile the permanence of death with the enduring nature of love.4. How does the interaction between Mo and Jenny Ping deepen our understanding of Mo’s situation and emotional state?

Answer:

The interaction with Jenny Ping provides insight into Mo’s vulnerability and the practical support system around him. Jenny’s surprise and concern—evident in her sarcastic greeting and insistence that Mo keep his phone on—highlight the precariousness of his situation and her role as a guardian. Her casual demeanor, contrasted with genuine care, offers Mo a semblance of stability and comfort amid his grief. The dialogue reveals Mo’s resistance and emotional fragility, especially when he begins to tremble and cannot speak. Jenny’s empathy and offer of tea and snacks acknowledge both his emotional and physical needs, emphasizing the importance of community care in healing.5. Reflect on the theme of guardianship as presented through Jenny’s role and her conversation with Mo. How might this theme develop in the story?

Answer:

Guardianship emerges as a central theme through Jenny’s role as Mo’s appointed protector after his grandmother’s death. Jenny’s admonitions and caring attitude illustrate the responsibilities and challenges inherent in guardianship, especially for someone like Mo who is struggling emotionally. She emphasizes the need for communication, safety, and boundaries, suggesting that guardianship involves both care and authority. This theme likely develops to explore how Mo navigates his grief while adapting to new support systems and how Jenny balances firmness with compassion. It also raises questions about autonomy, trust, and the complexities of caring for someone in transition, setting the stage for character growth and relational dynamics.

Quotes

1. “No sooner did you have a body again than, hooray, you were reminded of the undignified demands the body places upon you.”

This quote poignantly captures Mo’s conflicted state as he returns to life, highlighting the often overlooked physical realities that accompany existence, setting a somber tone for the chapter’s exploration of grief and bodily needs.

2. “Love only lasts so long. Sometimes only slightly longer than pastries and shortbread. Though hadn’t Mo’s grandmother loved Mo all of his life?”

Here, the narrative reflects on the transient nature of love contrasted with the enduring love between Mo and his grandmother, underscoring the bittersweet reality of human relationships and loss central to the chapter’s emotional core.

3. “Jenny said, ‘Never mind. I don’t want to know. Just, next time you go for a stroll in the middle of the night, would you please take your phone with you? And keep it turned on? I get we haven’t talked much about how all this is going to work, but if I’m going to do this guardian thing, then you need to at least pretend I get to tell you what to do once in a while.’”

This quote introduces the dynamic between Mo and Jenny, revealing themes of care, responsibility, and the negotiation of boundaries amid difficult circumstances, marking a turning point toward support and connection in the chapter.

4. “‘Me, when I’m feeling awful, I eat until it doesn’t hurt anymore. Store-brand vanilla ice cream. Or frozen peas. Or tuna. Right out of the can. I’m not particular.’”

Jenny’s candid admission offers a relatable insight into coping mechanisms for emotional pain, humanizing her character while emphasizing the raw, unvarnished ways people manage grief and distress, a subtle but meaningful moment in the chapter.