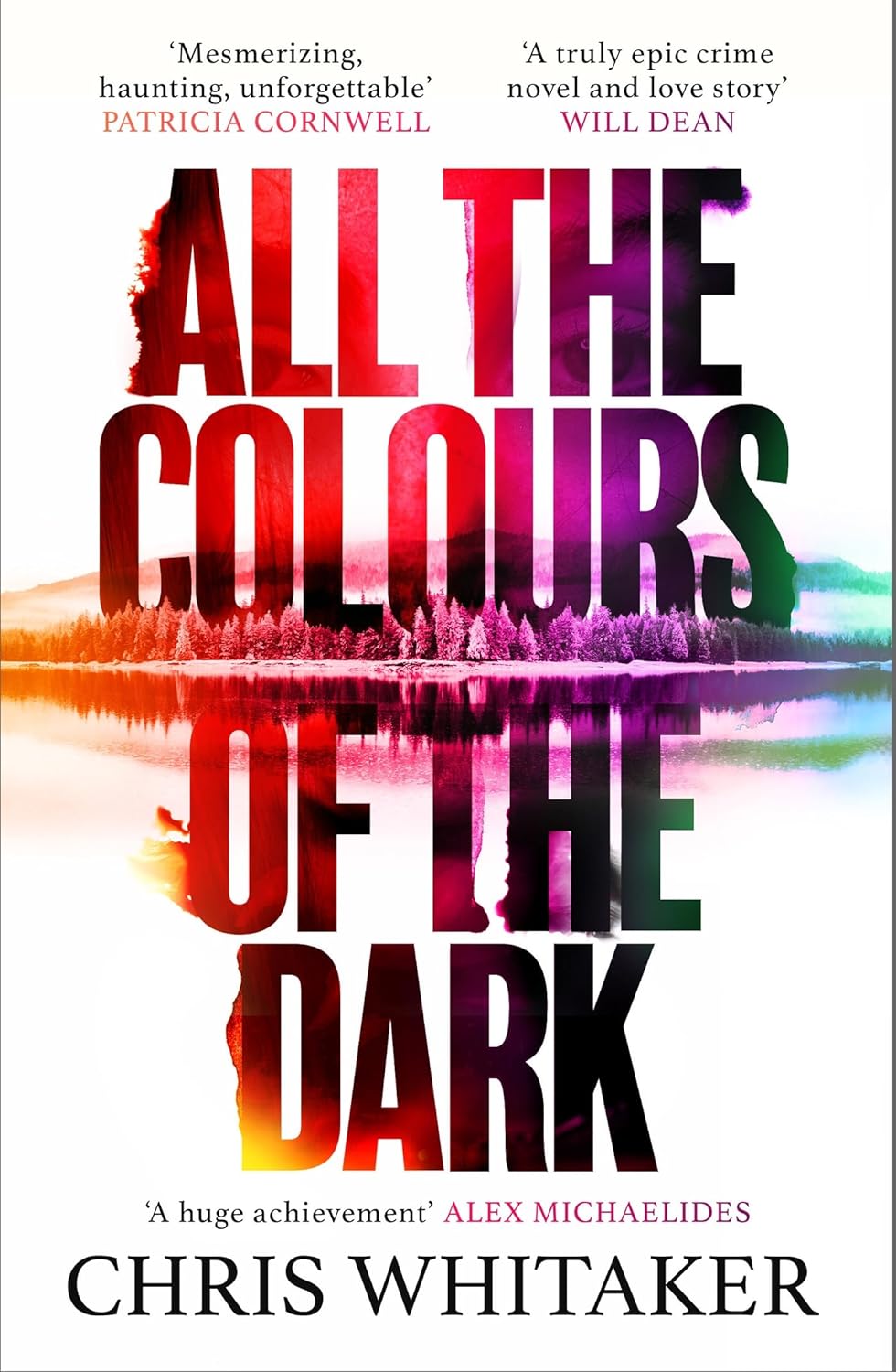

All the Colors of the Dark

Chapter 70

byChapter 70 opens with Patch hunched over a book on a quiet bus ride. The small-town library in Pecaut had offered him a modest collection—Modern Art, Cityscapes, and Realizing Portrait. He flips pages slowly, absorbing the brush techniques and tonal principles with a kind of devotion, each word a tiny key to unlocking a face he cannot forget. On every bus, he studies under the hum of flickering lights, looking for hints on how to better capture emotion, loss, and memory on canvas. The books become companions, even mentors, in a journey that’s becoming more spiritual than logistical.

When he reaches Lewisville, a town stitched together with cracked sidewalks and brick storefronts, Patch walks the streets with a quiet mission. Posters in hand, he tapes one onto a streetlamp, then moves toward a weathered barber shop. A cop stops him with suspicion. But when he sees the artwork—a girl rendered in soft graphite lines, looking just over her shoulder with haunted eyes—the officer’s demeanor changes. Patch explains it’s not a missing person poster in the usual sense, though it lists a contact for the Monta Clare Police Department. Chief Nix, later overwhelmed by crank calls triggered by these flyers, doesn’t share Patch’s quiet optimism.

He moves from town to town—Le Masco, Afton, Saddlers Clay, and Lenard Creek. Many of these places are more memory than map, barely marked by highway signs or open shops. Along the way, Patch makes a brief stop to see Norma, who offers him a ride and mentions her granddaughter. Norma’s eyes hint at deeper concern. She tells him the girl has been skipping school, haunted by something unspoken. At Loess Hills, where the bus veers from its usual route, Norma asserts herself with calm authority, brushing off an older man’s complaints with practiced indifference. The world they pass seems to blur, but for Patch, each town holds the potential of a new clue, or a new memory rediscovered.

Darby Falls feels both familiar and alien as Patch approaches the Montrose home. Richie Montrose, weathered by time and sorrow, answers the door with the soft shuffle of someone expecting nothing. The house smells faintly of beer and dust. The living room is in disarray, littered with empty cans and the static buzz of a baseball game on an old TV. Richie’s voice is low, hesitant. He asks why Patch is there. The name “Callie” hangs in the air between them. Patch doesn’t claim certainty—only a deep, aching hope.

Richie finally lets Patch into Callie’s old room. It’s untouched. The room feels paused in time, as if Callie might walk back in at any moment. There are posters on the wall, notes scribbled and stuck to a mirror, and a stuffed bear on the edge of the bed. Patch moves slowly through the space, taking it all in. Every item is a breadcrumb, and he follows them with care, looking for echoes of the girl who once laughed there. He asks Richie small questions—what music Callie liked, who her closest friends were—but Richie’s answers are fogged by grief.

Downstairs, a Johnny Cash record starts spinning on an old turntable. Patch hears the first few lines and stops. The sound cuts through him like memory often does—soft at first, then full of weight. He stands there, listening, absorbing the music like it’s another clue. In that voice, he hears everything he can’t say out loud—loss, longing, and a quiet determination to keep going. Patch closes his eyes briefly. He can almost see Grace’s face again, not in the posters or paintings, but in the fragments of emotion that rise unexpectedly.

By the end of Chapter 70, Patch doesn’t find a resolution. But what he gains is something more subtle—a quiet affirmation that his path, however winding, matters. Each poster, each knock on a stranger’s door, adds weight to the invisible thread that binds the missing and those still searching. Even in the silence that follows the music, Patch finds resolve. He steps back onto the porch, into the gray afternoon light, carrying Callie’s memory with him like one more color on his palette. His work, though incomplete, is far from over.

0 Comments