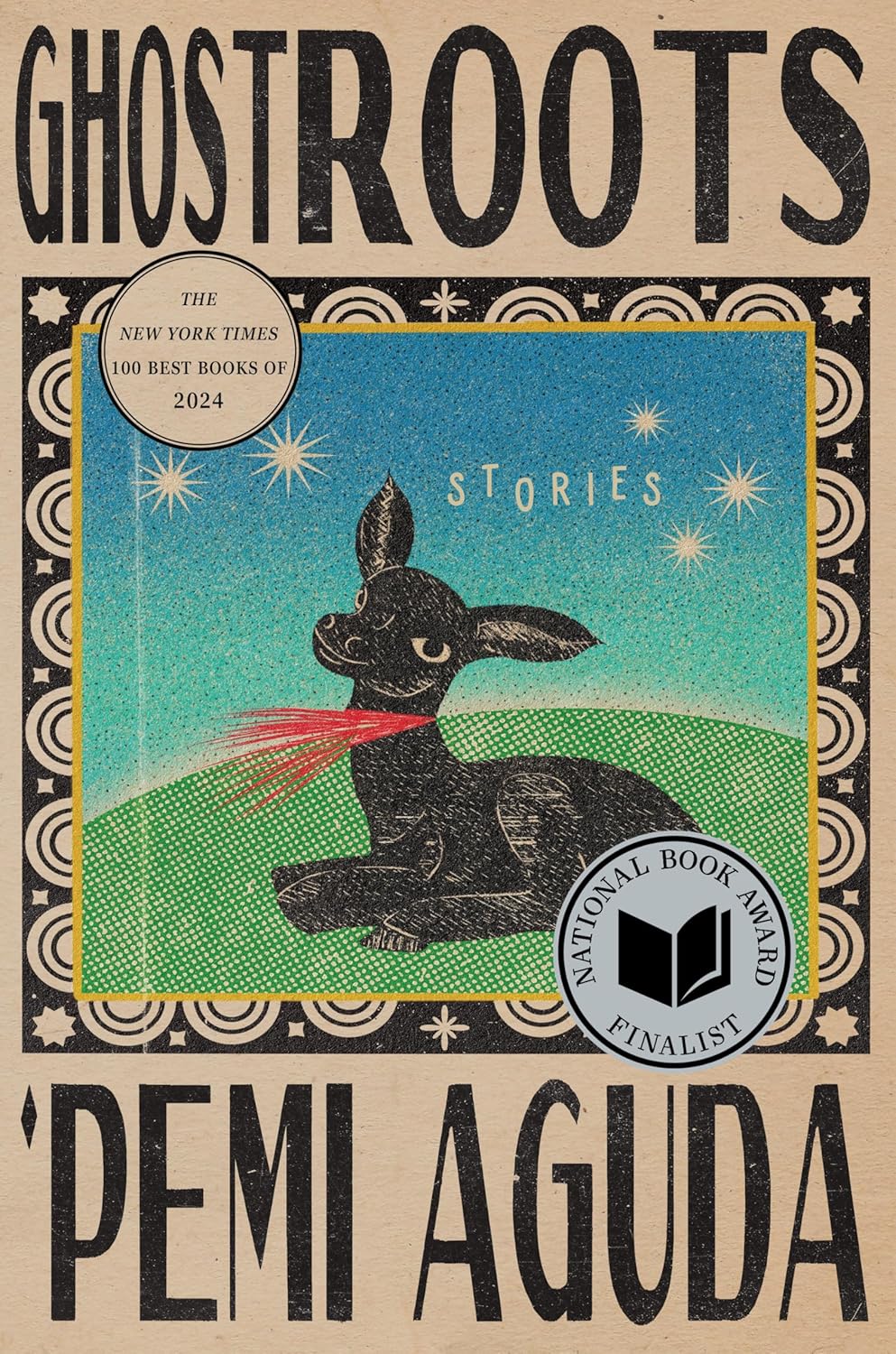

Ghostroots

Contributions

by Aguda, ‘PemiThe chapter describes a tight-knit group of women who practice “esusu,” a traditional rotating savings system where members contribute money monthly, and each takes turns receiving the pooled funds. The system relies on strict rules and mutual trust, with severe consequences for those who fail to meet their obligations. The women pride themselves on self-sufficiency, rejecting banks and loans, and enforcing order through collective discipline. Past incidents, such as seizing a generator or temporarily taking a member’s daughter, illustrate their uncompromising approach to maintaining the system’s integrity.

When a new woman joins the group, she initially adheres to the rules, participating in meetings and paying her contributions on time. However, she soon begins to struggle financially, pleading for extensions. The group, following their established protocol, seizes her husband and later her mother as collateral, but both prove ineffective—her husband is lazy and disruptive, while her mother transforms into animals and escapes. Frustrated, the group demands alternative forms of repayment, leading the woman to offer her body parts piece by piece.

The woman surrenders her arms, legs, torso, and eventually her head, each part serving a practical purpose in the group’s daily lives—chopping vegetables, comforting children, or providing emotional support. Yet, despite her sacrifices, she remains unable to fulfill her financial obligations. The group continues taking her body parts, only realizing too late the consequences of their actions. The woman’s voice grows increasingly faint as she diminishes, leaving the group to confront the unsettling reality of their relentless enforcement.

In the end, the chapter highlights the dangers of rigid systems that prioritize rules over humanity. The women’s unwavering adherence to their collective savings scheme leads them to dehumanize the new member, stripping her of her body and identity. The narrative serves as a critique of unchecked power and the moral costs of absolute discipline, leaving the group to grapple with the unsettling outcome of their actions.

FAQs

1. What is the esusu system described in the chapter, and how does it function within the women’s group?

Answer:

The esusu system is a traditional rotating savings scheme where each member contributes a fixed amount of naira monthly. Names are listed in random order, and each month, the next person on the list collects the pooled funds. This cycle repeats until all members have received their turn. The system relies on strict adherence to rules—defaulters face consequences like property seizure or temporary loss of family members (e.g., Iya Ibeji’s generator or Mrs. B’s daughter). The chapter emphasizes its self-sufficiency (“We don’t need your banks”) and the importance of maintaining order to prevent collapse.2. How does the group enforce compliance when members fail to meet their contributions, and what does this reveal about their values?

Answer:

The group enforces compliance through punitive measures that target defaulters’ assets or loved ones, such as seizing a frozen food store’s generator or temporarily taking a daughter to perform domestic labor. These actions reflect their prioritization of collective trust and systemic stability over individual compassion. As stated, “If we show pity even once, our structure will collapse.” The extreme measures—like seizing the new woman’s body parts—highlight their rigid adherence to rules and the lengths they’ll go to preserve the system, even at the cost of humanity or practicality.3. Analyze the symbolic significance of the new woman’s transformation and the group’s reaction to her “contributions.”

Answer:

The new woman’s gradual surrender of her body parts (arms, legs, torso, head) symbolizes the dehumanizing consequences of financial desperation and systemic rigidity. Her voice grows “airier” with each loss, suggesting diminishing agency. The group’s initial practicality (using her arms for chores) shifts to absurdity as they accept useless parts like her “heavy head,” revealing their blind adherence to rules over reason. The surreal outcome—where they realize “what she had done” too late—critiques systems that prioritize mechanics over morality, leaving both parties diminished.4. How does the chapter explore themes of power and vulnerability through the esusu system?

Answer:

Power dynamics are central: the group wields collective authority to enforce rules, while members (especially defaulters) face vulnerability. The system empowers women economically (“We can take care of ourselves”) but also exposes them to exploitation, as seen with the new woman’s extreme sacrifices. The seizure of family members (husband, mother) and body parts underscores how financial systems can commodify human relationships and autonomy. The group’s insistence on “no leniency” reveals how marginalized communities might replicate oppressive structures to protect their fragile stability.5. What cultural and social commentary does the chapter offer through its portrayal of the esusu system?

Answer:

The chapter critiques both traditional and modern financial systems. The esusu system is portrayed as a resilient, community-based alternative to banks, yet its brutality mirrors the impersonal harshness of institutional lending. The group’s rejection of “stupid leniency” reflects a survival mindset born from systemic exclusion (“the gutters”). Meanwhile, the new woman’s plight—and her mother’s metamorphosis into animals—satirizes how financial obligations can distort humanity. Ultimately, the chapter questions whether any system, no matter how communal, can escape corruption when driven by scarcity and fear.

Quotes

1. “We don’t need your banks; we don’t need your loans. We can take care of ourselves.”

This quote encapsulates the self-reliant ethos of the esusu system, a traditional rotating savings scheme. It highlights the women’s pride in their collective financial independence and their rejection of formal banking institutions.

2. “If we show pity even once, our structure will collapse on itself, so we seized Mrs. B’s daughter.”

This demonstrates the harsh but necessary enforcement mechanisms of the esusu system. The quote reveals how the women maintain order through extreme measures, prioritizing the system’s survival over individual compassion.

3. “We’ve worked too hard to allow any stupid leniency that could risk sending us back to the gutters.”

This powerful statement explains the women’s uncompromising attitude toward newcomers. It reflects their collective trauma and determination to maintain their hard-won financial security at all costs.

4. “He looked at us and reminded us of the expanse of our hips, the heft of our breasts; reminded us of the ways our bodies take up space.”

This poetic yet unsettling observation occurs when the group seizes the new member’s husband. It reveals how the women become uncomfortably aware of their own physicality through this unusual enforcement tactic.

5. “We took and we took and we took. It wasn’t until we had all her body parts that we saw what she had done.”

This climactic quote shows the shocking culmination of the system’s enforcement measures. The gradual dismantling of the woman’s body serves as a powerful metaphor for both the system’s brutality and its eventual revelation of some deeper truth.