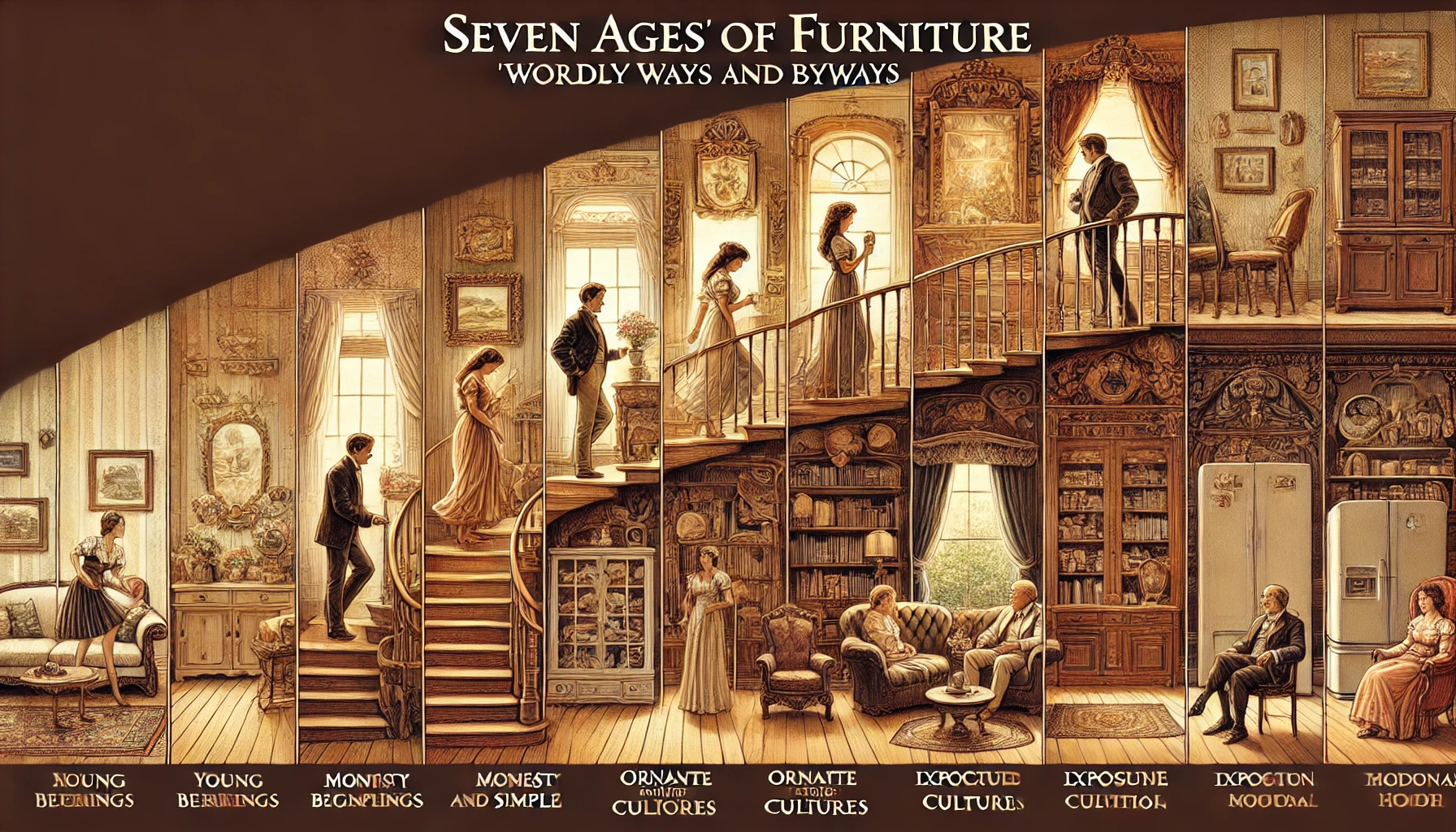

Chapter 12 — “Seven Ages” of Furniture

byChapter 12 – “Seven Ages” of Furniture opens with a humorous but sharp observation of how American couples evolve in their tastes for home décor, often without knowing exactly why. At the beginning of their married life, most young couples furnish their homes with mismatched items—gifts from relatives or leftover pieces with no aesthetic cohesion. These early arrangements feel more functional than intentional, reflecting a stage of life defined by practicality rather than taste. There is little room for artistic vision when furniture is inherited rather than selected. These bulky, outdated pieces fill the space, but they say more about the couple’s lack of agency than any sense of identity. It’s not just a lack of style—it’s the result of beginning adulthood under the shadow of other people’s choices.

Then moves into a more decorative, though equally unsteady, phase: the Japanese-inspired period. Here, the young wife takes her first real initiative in shaping the home, layering it with silk fans, bamboo tables, and gauzy curtains. While the effort reflects personal growth, it’s driven more by fads than an understanding of culture or design. Oriental trinkets and paper lanterns appear not as acts of curation but of imitation, nodding toward a distant culture without engaging its meaning. Her taste expands, but superficially—mirroring an aesthetic awakening that is earnest, yet premature. This shift, though flawed, marks the couple’s attempt to move beyond hand-me-downs and into a world of their own making. It’s a transitional stage of enthusiasm over expertise.

Financial prosperity invites the third phase: one of indulgence cloaked as refinement. Flush with money, the couple replaces their makeshift aesthetic with elaborate but unharmonious furniture, gilded mirrors, tufted satin, and over-designed interiors. Their home becomes a showroom of luxury, but not necessarily of good taste. Inlaid woods, mirrored cabinets, and carved consoles dominate rooms that feel heavy rather than elegant. The pursuit of beauty is sincere, but guided by catalogues, not comprehension. Every new purchase reflects a desire to prove they’ve arrived, yet the result is more chaotic than cultured. Wealth, instead of empowering thoughtful design, enables excess without restraint.

Later stages attempt to borrow sophistication through imitation. They try to emulate the somber grandeur of English country houses with dark wood, stained glass, and heavy drapery, producing what the author wryly calls an “ecclesiastical junk shop.” Their home begins to resemble a pastiche of religious symbolism and borrowed nostalgia, devoid of intimacy. When they eventually build a grander house, they swing toward French opulence—gilt-framed mirrors, brocade upholstery, and marble busts fill every corner. But instead of reflecting nobility, the design feels strained, like a costume worn without confidence. In both phases, the couple is chasing authenticity through replication, rather than discovering their own style. They want their home to speak fluently in the languages of aristocracy, but they’re still learning the grammar.

Eventually, disillusionment sets in. The expensive furniture no longer excites, the layered styles feel disjointed, and the couple begins to sense something hollow in their meticulously curated environment. They realize their journey through design hasn’t been one of artistic enlightenment, but of trend-following and misinterpretation. There’s a quiet humility in this realization—they finally acknowledge that genuine taste requires guidance, study, and emotional intelligence. The home is no longer just a social symbol; it becomes a mirror for their own growth. They begin to value restraint, balance, and meaning over flash and imitation. Their focus turns not to impressing others, but to creating a space that reflects who they are—not who they wanted to appear to be.

This chapter offers more than a satire of interior design—it critiques how culture is often consumed rather than understood. As the couple passes through each “age” of furniture, they represent broader societal trends where wealth substitutes for knowledge and decoration replaces depth. True artistry, the author suggests, is not found in what money can buy, but in how thoughtfully space is considered and lived in. The evolution of their home becomes a metaphor for the evolution of character—a slow, often misguided, but ultimately human pursuit of meaning through material expression. In recognizing their limitations, the couple opens the door to something more lasting: the possibility of taste shaped by truth rather than trend.