Bloody Sunday

byOn Bloody Sunday, April 14, 1861, the weather was warm and bright, setting the stage for one of the most pivotal moments in American history—the evacuation of Fort Sumter. The anticipation was palpable as the Palmetto Guard, led by Edmund Ruffin, boarded a steamer, joining a large crowd of spectators who had gathered along the harbor to witness the departure of Major Anderson and his garrison. The originally planned 9 a.m. evacuation was delayed, extending the wait into the afternoon. As the clock ticked, Major Anderson boarded the Catawba, preparing to transfer his men to the Isabel, which would then take them to the awaiting Baltic. As Anderson prepared to leave, questions arose about a cannon salute to mark the occasion. Responding emotionally, Anderson stated, “No, it is one hundred, and those are scarcely enough,” before succumbing to tears. His words, full of regret and sorrow, underscored the emotional toll of the day and the profound loss felt by the Union as they relinquished control of Fort Sumter.

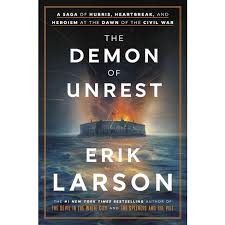

During the wait, Ruffin took note of the fort’s resilience, observing how it had survived the intense bombardment largely unscathed. Despite the heavy cannon fire directed at the fort, there was little damage, which contrasted sharply with the heavy emotional weight of the moment. By nearly 3 p.m., the first of the expected hundred cannons rang out, marking the official end of Anderson’s time at the fort. The noise echoed across the harbor, a fitting yet somber tribute to the conclusion of the standoff. The atmosphere shifted from one of tension to quiet contemplation as the cannon’s sound faded away. Meanwhile, Captain Doubleday organized the Union soldiers into their final formation, preparing for the lowering of the flag. As planned, the cannon salute began, but tragedy struck when a misfire occurred, resulting in the death of Private Daniel Hough, who was hit by the blast. The salute was halted immediately, and a hurried burial took place in the midst of the somber moment. The presence of both Confederate and Union soldiers during this act of respect emphasized the human cost of the conflict that was about to unfold.

After the burial of Private Hough, the salute resumed, though it was reduced to fifty rounds in honor of the fallen soldier. The mood remained somber as the Union soldiers prepared to leave the fort. By 4 p.m., Major Anderson led his men away from the fort, accompanied by the tunes of “Yankee Doodle,” a song that resonated with the Union soldiers despite the difficult circumstances. As the procession moved toward their departure, the atmosphere in the harbor became more charged with emotion. In Charleston, celebrations erupted with fireworks lighting up the night sky, signifying the Confederate victory and the beginning of a new chapter for the South. The Confederate victory, achieved without a single loss of life during the bombardment, was perceived as a triumph. This moment symbolized Southern strength and resolve, signaling the start of a fierce and uncertain future. However, the irony of the day lay in the fact that despite the countless cannonballs exchanged during the bombardment, no one had died in the conflict itself. This peaceful yet emotionally charged surrender marked the beginning of a civil war that would soon escalate, claiming the lives of hundreds of thousands and altering the course of American history forever. Bloody Sunday, therefore, was a day of dual meanings: a symbol of both triumph and tragedy that foreshadowed the devastation that would come in the years ahead. The day itself set the stage for the war’s deep divisions and the violent conflict that would eventually define the nation’s future.