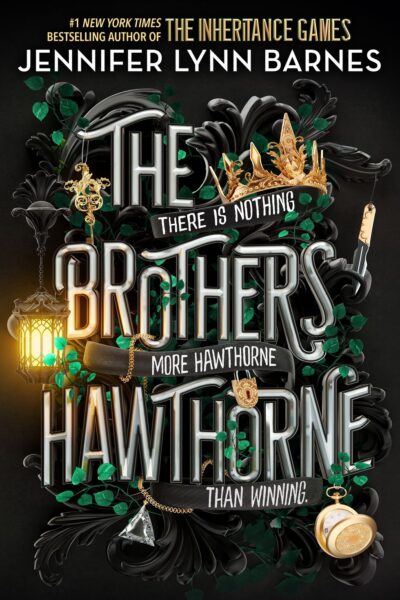

The Brothers Hawthorne

CHAPTER 25: JAMESON

by Barnes, Jennifer LynnJameson discovers that Rohan is not merely a messenger but the Factotum, the right-hand man of the mysterious Proprietor of the Devil’s Mercy. The chapter opens with Jameson recalling Ian’s cryptic words about the Proprietor’s succession and the organization’s hidden workings. Avery confronts Rohan about the unethical use of child labor, to which Rohan responds with a chilling justification, hinting at his own traumatic past. The tension escalates as Rohan unlocks a hidden door, inviting them into a secretive world with a foreboding warning: “The house always wins.”

The setting inside the Devil’s Mercy is opulent yet ominous, featuring a domed Roman-style room with five grand arches, each representing a deadly sin. Jameson notes the intricate design, including marble arches, black curtains, and a central infinity symbol made of onyx and agate. Rohan’s disembodied voice demonstrates the room’s acoustic tricks, adding to the surreal atmosphere. As Jameson and Avery explore, Rohan reveals the purpose of each archway, starting with Sloth (massage and relaxation) and Gluttony (gourmet food and drinks), all while maintaining a playful yet threatening demeanor.

The tour continues with Lust, where private chambers hint at illicit activities, and Rohan issues a stark warning against non-consensual actions. The fourth archway reveals Wrath, a boxing ring where members gamble on brutal fights. Rohan’s description of the violence and his ambiguous history with the ring suggest a darker underbelly to the Mercy’s operations. Jameson’s curiosity and competitive nature are piqued, but the underlying danger is palpable, reinforcing the theme of risk and consequence that permeates the chapter.

Throughout the chapter, Jameson’s strategic mind analyzes every detail, drawing parallels between the Mercy’s labyrinthine design and his own family’s secrets. The dynamic between him, Avery, and Rohan is charged with unspoken threats and power plays. The chapter culminates in a sense of anticipation as Jameson prepares to navigate this treacherous world, where every choice could lead to victory or ruin. The Devil’s Mercy emerges as a place where desire and danger intertwine, and Jameson’s resolve to outplay the house is put to the test.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of Rohan’s true identity as the Factotum, and how does this revelation impact Jameson’s understanding of the situation?

Answer:

The revelation that Rohan isn’t just a messenger but the Factotum—the right-hand man and potential successor to the Proprietor—reshapes Jameson’s understanding of the power dynamics at play. Earlier, Ian had hinted that Jameson needed the Proprietor’s attention, not his subordinate’s, suggesting Rohan holds substantial influence. This realization forces Jameson to recalibrate his approach, recognizing Rohan as a key player in the Devil’s Mercy hierarchy. The chapter implies Rohan’s childhood connection to the organization (“those it does save rarely regret it”) further cements his authority, making him both a gatekeeper and a potential threat in Jameson’s strategic calculations.

2. Analyze the symbolic elements in the domed room’s design. How do they reflect the themes and purpose of the Devil’s Mercy?

Answer:

The domed room is rich with symbolism that mirrors the Devil’s Mercy’s dual nature of allure and danger. The five arches represent the five deadly sins (Sloth, Gluttony, Lust, Wrath, Envy/Pride), framing the club’s offerings as temptations. The lemniscate (infinity symbol) in black onyx and white agate suggests endless cycles of risk and reward, while the floating lilies—often symbols of purity—ironically contrast with the venue’s decadence. The multiple hidden doors and echoing acoustics create an atmosphere of illusion and surveillance, reinforcing Rohan’s warning: “the house always wins.” These elements collectively paint the Mercy as a carefully crafted trap masquerading as paradise.

3. How does Rohan’s warning about consent in the Lust archway complicate the reader’s perception of the Devil’s Mercy’s moral code?

Answer:

Rohan’s stark threat—”lay a hand on anyone who does not want a hand there… and I cannot guarantee you will still have a hand”—introduces a paradoxical moral boundary within an otherwise lawless space. While the Mercy profits from vice, this rule suggests it enforces brutal consequences for violating personal autonomy. This contradiction hints at an internal hierarchy of sins: exploitative violence is punishable, while consensual indulgence is commodified. It also positions Rohan as an ambiguous figure—both a protector (of vulnerable staff) and an enabler of corruption—deepening the tension between the club’s glamorous facade and its underlying brutality.

4. Compare Jameson’s reaction to the Mercy’s challenges with Avery’s. What does their dynamic reveal about their respective characters?

Answer:

Jameson immediately engages with the Mercy as a puzzle to solve, noting architectural details (hidden doors, materials) and testing Rohan with quips (“Lust?”). His focus on strategy and his competitive glare when Avery takes Rohan’s arm reveal his calculative, possessive nature. Avery, meanwhile, confronts Rohan directly about ethics (“Child labor? That can’t be legal”), showcasing her moral clarity and boldness. Their dynamic highlights Jameson’s comfort with ambiguity and gamesmanship versus Avery’s instinct to challenge injustice. Yet both share fearlessness—Jameson strides in without hesitation, and Avery demands answers—suggesting their complementary strengths could either clash or synergize in later confrontations.

5. Why might the author have chosen to structure the Devil’s Mercy around the five deadly sins? Discuss the narrative and thematic implications.

Answer:

The five-sins framework serves both narrative and thematic purposes. Structurally, it organizes the club’s offerings into distinct, escalating tiers of temptation (from passive Sloth to violent Wrath), allowing gradual revelation of its depravity. Thematically, it mirrors the characters’ moral descent: each archway represents a potential test for Jameson and Avery, foreshadowing future choices. Historically, the sins also evoke the Faustian bargain central to the club’s name (“Devil’s Mercy”), suggesting membership requires soulful compromise. By modernizing these ancient vices in a lavish setting, the author critiques how power systems repackage corruption as exclusivity—a theme resonant with the Hawthorne family’s own conflicts with privilege and morality.

Quotes

1. “Rohan didn’t work for the Factotum. Rohan was the Factotum. Not just a messenger.”

This revelation about Rohan’s true identity as the Factotum (not merely an employee) establishes his power and significance in the Devil’s Mercy organization, setting the stage for his authoritative role throughout the chapter.

2. “A certain type of child knows how to keep secrets better than adults. The Mercy can’t save every child it finds in a horrific situation, but those it does save rarely regret it in the end.”

This morally ambiguous statement about child labor in the organization reveals the Mercy’s dark recruitment practices and Rohan’s personal history, hinting at the complex ethics of the underground world.

3. “Where angels fear to tread, have your fun instead. But be warned: The house always wins.”

Rohan’s chilling welcome encapsulates the Devil’s Mercy’s philosophy - a playground for vices where participants are ultimately at the mercy (pun intended) of the establishment’s control.

4. “Each area is dedicated to a deadly sin. We are, after all, the Devil’s Mercy.”

This explanation of the five archways’ symbolism reveals the thematic organization of the Mercy’s offerings, directly tying the establishment’s structure to its sinful, devilish identity.

5. “If you end up in a disagreement with another player at the tables, however, you’re welcome to take the disagreement to the ring. Wrath? Envy? Pride? People end up in the ring for all kinds of reasons.”

This description of the boxing ring area demonstrates how the Mercy channels and monetizes human vices and conflicts, with violence serving as both entertainment and conflict resolution.