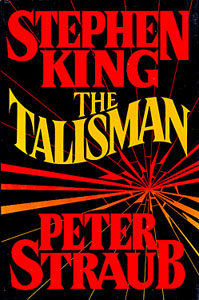

The Talisman: A Novel

Chapter 10: Jack in the Pitcher Plant

by King, StephenJack Sawyer, desperate and fearful, hides in the storeroom of the Oatley Tap, planning to escape after closing time. The repetitive thought “I was six” echoes in his mind, reflecting his growing terror and confusion. The bar is overcrowded and chaotic, with a loud band and rowdy patrons amplifying his sense of entrapment. Jack’s unease is compounded by Smokey Updike, the bar’s intimidating owner, who has an unsettling hold over him, making his situation feel increasingly inescapable.

As Jack struggles to move a heavy keg, he recalls a previous mishap where Smokey violently punished him for spilling beer. The memory reinforces his fear of Smokey’s unpredictable brutality and the grim realization that Smokey expects him to stay indefinitely. The physical labor and the threat of further violence heighten Jack’s desperation to flee, but the oppressive atmosphere of the bar and Smokey’s dominance make escape seem daunting.

The chapter vividly portrays Oatley as a nightmarish trap, likened to a pitcher plant—easy to enter but nearly impossible to leave. Jack’s encounters with unsettling figures, like the man resembling Randolph Scott with shifting eye colors, deepen his paranoia. The town itself feels malevolent, as if designed to ensnare him. The graffiti and hostile interactions in the bar’s hallway mirror the town’s underlying hostility, reinforcing Jack’s isolation and vulnerability.

Jack’s resolve to run away underscores his deteriorating mental state and the urgency of his predicament. The chapter builds tension through sensory details—the deafening noise, the stifling storeroom, and the looming threat of Smokey—painting a claustrophobic picture of Jack’s entrapment. His determination to escape, despite the overwhelming odds, sets the stage for a pivotal moment in his journey, highlighting his resilience amid escalating danger.

FAQs

1. How does the chapter establish Jack Sawyer’s psychological state, and what literary techniques are used to convey this?

Answer:

The chapter portrays Jack’s deteriorating mental state through internal monologue (“I was six, six, John B. Sawyer was six”), sensory overload (the vibrating walls, roaring crowd), and physical distress (sweating, back pain). The repetitive thought about being six functions as a psychological motif, suggesting trauma or regression under stress. King uses stream-of-consciousness writing (“round and round she goes”) and visceral imagery (gooseflesh, throbbing fingers) to immerse readers in Jack’s fear and disorientation. The contrast between his current desperation (“running away”) and his earlier resolve in the Oatley tunnel further underscores his unraveling.2. Analyze how Smokey Updike functions as an antagonist in this chapter. What makes him particularly threatening to Jack?

Answer:

Smokey embodies psychological and physical domination. His threats (“you never want to do that again”) imply long-term control, while his violence (the looping punch) demonstrates immediate brutality. The chapter emphasizes his unsettling traits: “violent brown eyes,” “funereal” dentures, and unpredictable anger over spilled beer. Most disturbingly, Smokey’s power stems from ambiguity—Jack doesn’t understand how he became “taken prisoner,” making the threat more existential. The economic coercion (withholding pay) and public humiliation (forcing Jack to handle kegs poorly) compound the menace, positioning Smokey as both a personal tormentor and symbol of Oatley’s inescapable trap.3. What symbolic significance does the pitcher plant metaphor hold for Jack’s situation in Oatley?

Answer:

The pitcher plant metaphor encapsulates Jack’s entrapment. Like insects lured by nectar, Jack entered Oatley voluntarily but now finds escape nearly impossible due to Smokey’s control, the town’s hostility (racist graffiti), and psychological fatigue. The plant’s digestive enzymes parallel Oatley’s corrosive environment—the “bilious green” hallway reeking of waste, the dehumanizing labor, and the predatory locals (“guys that’d fuck a pedal-steel”). This biological metaphor transforms the town into an active, consuming entity, suggesting Jack’s struggle isn’t just against people but against the very fabric of the place itself.4. How does the chapter use sensory details to create atmosphere, and what effect does this have on the reader?

Answer:

King employs overwhelming sensory input to mirror Jack’s distress. Auditory details dominate: the jukebox’s “Saturn rocket” volume, the crowd’s “wave of sound,” and Lori’s shouts piercing through noise. Tactile elements (chilly storeroom, kegs grinding on cement) emphasize physical strain, while olfactory cues (urine, TidyBowl) reinforce disgust. Visual grotesquerie—Smokey’s dentures, the “swinging gut” of a patron—heightens unease. This multisensory barrage immerses readers in Jack’s claustrophobic experience, making Oatley feel viscerally real and inescapable. The contrast between the taproom’s chaotic energy and the storeroom’s damp isolation further underscores Jack’s alienation.5. What does the graffiti in the hallway reveal about Oatley’s societal dynamics, and how does this contribute to the chapter’s themes?

Answer:

The racist, antisemitic graffiti (“SEND ALL AMERICAN NIGGERS AND JEWS TO IRAN”) exposes Oatley’s bigotry and scapegoating mentality. Its “dull and objectless fury” reflects communal frustration channeled into hatred rather than addressing systemic issues (likely economic, given the textile/rubber factory workers). This environment of intolerance mirrors Jack’s persecution—both are outsiders targeted without reason. The public nature of the graffiti (in a high-traffic area) suggests such views are normalized, deepening the chapter’s themes of entrapment and dehumanization. It positions Oatley not just as physically dangerous but morally corrosive, amplifying Jack’s need to escape.

Quotes

1. “Not quite sixty hours later a Jack Sawyer who was in a very different frame of mind from that of the Jack Sawyer who had ventured into the Oatley tunnel on Wednesday was in the chilly storeroom of the Oatley Tap, hiding his pack behind the kegs of Busch which sat in the room’s far corner like aluminum bowling pins in a giant’s alley.”

This opening line establishes Jack’s transformed mental state and desperate situation, comparing his current trapped existence to his earlier freedom. The bowling pin simile underscores his vulnerability in this hostile environment.

2. “Oatley, New York, deep in the heart of Genny County, seemed now to be a horrible trap that had been laid for him… a kind of municipal pitcher plant. One of nature’s real marvels, the pitcher plant. Easy to get in. Almost impossible to get out.”

This powerful metaphor captures the chapter’s central theme of entrapment, comparing the town to a carnivorous plant that ensnares its prey. It reflects Jack’s growing realization of Oatley’s sinister nature and his dwindling hope of escape.

3. “What chilled Jack most about that phrase you never want to do that again was what it assumed: that there would be lots of opportunities for him to do that again; as if Smokey Updike expected him to be here a long, long time.”

This insight reveals the psychological terror of Jack’s captivity, showing how Smokey’s casual threat implies an endless future of servitude. It marks a turning point in Jack’s understanding of his predicament.

4. “The dead phone that had finally spoken, seeming to encase him in a capsule of dark ice… that had been bad. Randolph Scott was worse… Smokey Updike was perhaps worse still… although Jack was no longer sure of that.”

This escalating list of horrors demonstrates Jack’s deteriorating mental state and the cumulative psychological weight of his experiences in Oatley. The “capsule of dark ice” image particularly stands out as a visceral metaphor for terror.

5. “SEND ALL AMERICAN NIGGERS AND JEWS TO IRAN, it read. The noise from the taproom was loud in the storeroom; out here it was a great wave of sound which never seemed to break.”

This shocking graffiti coupled with the relentless noise creates a powerful atmosphere of oppressive hostility, representing the town’s underlying bigotry and the constant psychological assault Jack endures.