Chapter 21 — The beasts of Tarzan

byChapter 21 – The beasts of Tarzan opens with a growing sense of urgency and strain among Tarzan’s group as they labor to complete a skiff needed for escape. The tension in the camp is palpable. Mugambi remains loyal and steadfast, but the same cannot be said of everyone. Schneider, a man already marked by suspicion, abandons his assigned tasks under the pretense of hunting. When he returns, he appears regretful, claiming to have spotted a herd of small deer in the jungle. This seemingly innocent news distracts Tarzan, who decides to take advantage of the opportunity to gather fresh meat. What Tarzan doesn’t know is that this momentary diversion is all part of a more sinister plan. Schneider’s real goal is not to hunt but to manipulate Tarzan into leaving the camp unguarded so that an abduction can be carried out without resistance.

As Tarzan disappears into the dense forest with his bow and instincts, the camp’s safety crumbles. Schneider quickly sends Mugambi away on a fabricated errand, reducing the number of defenders. This leaves Jane and the Mosula woman vulnerable. Meanwhile, Gust, a man with his own personal history tied to the villains, lurks in the shadows. He secretly follows Kai Shang and others, hoping to undermine their plans as part of his revenge. While his motivations are selfish, they intersect with justice at this moment. Gust discovers the conspiracy in motion—Jane is to be kidnapped, her protectors misled, and the captors will use the “Cowrie” to sail away. Without hesitation, Gust rushes to find Tarzan, knowing he must act quickly or all will be lost.

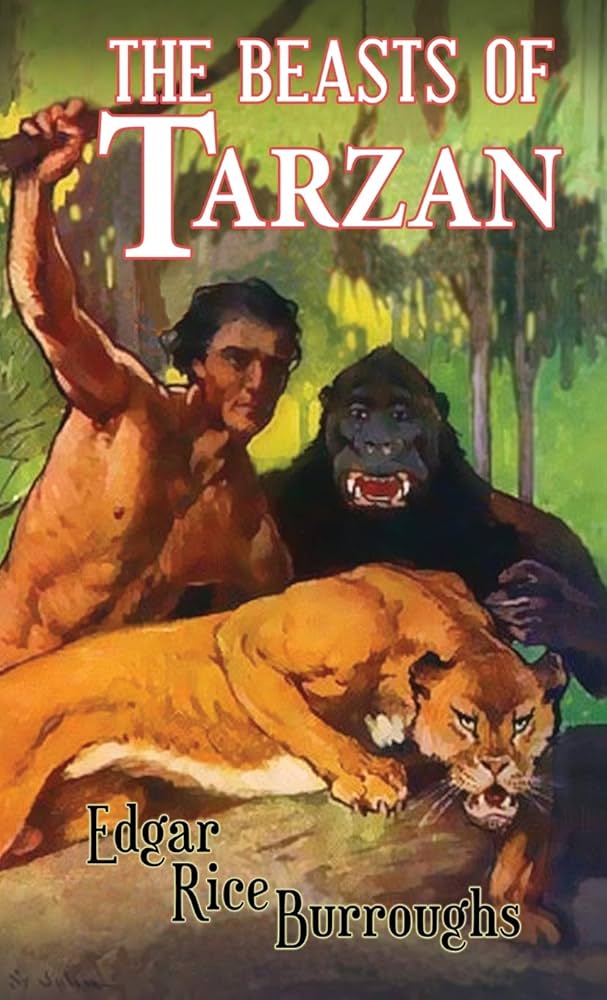

Tarzan, returning from the hunt with a growing sense of unease, finds the camp abandoned and silent. He instantly recognizes that Jane’s absence is not voluntary. Observing the ground, he notes signs of a hurried departure toward the coast. Before long, Gust emerges and confirms Tarzan’s suspicions. With fury building, Tarzan wastes no time in gathering a rescue party. He doesn’t call on men alone. With a deep bellow, he summons his jungle allies—beasts who trust him, follow him, and will fight for him without question. Sheeta, the sleek and deadly panther, appears from the underbrush, and Akut’s apes move through the trees like silent shadows. Together, they follow Tarzan into battle, their loyalty forged through shared struggles and respect.

Approaching the “Cowrie,” Tarzan launches a surprise assault. The jungle explodes with life as his animals overwhelm the crew. Screams echo across the beach as claws meet steel and apes seize their targets with unmatched ferocity. Amid the chaos, Tarzan fights his way through the fray, rescuing Jane and the Mosula woman. In this storm of violence and justice, no mercy is shown to the guilty. Schneider tries to escape but is dragged before Tarzan. There is no trial. Tarzan, burned by previous betrayals, delivers a swift and final punishment. The jungle offers no second chances when loyalty is broken.

With order restored, Tarzan takes command of the “Cowrie.” Those who had sided with the traitors are forced to serve under strict supervision, their lives hanging by a thread. The ship is redirected to Jungle Island, where Tarzan thanks his animal allies and sets them free. Their roles complete, the beasts disappear into the green, reminders of the bond Tarzan shares with the wild. Shortly after, a passing steamer offers communication with the outside world. From this, Tarzan learns that his son, Jack, is alive and safe in England. A web of deception spun by Rokoff and Paulvitch is finally exposed. Their plot failed, but only narrowly.

The reunion between Tarzan and Jane is bittersweet. Relief floods their hearts, but the pain of near loss lingers. Their son’s safety, ensured by luck and courage, marks the true end of their ordeal. Back in civilization, they reflect on everything they’ve endured—betrayal, danger, survival. The jungle tested them, and they emerged stronger. Tarzan’s sense of justice is clear: wrongdoers are punished, and those he loves are protected at any cost. The island is left behind, the beasts vanish into legend once more, and peace returns. But the memory of this chapter, shaped by instinct, bravery, and retribution, becomes yet another defining story in the life of the jungle’s greatest protector.