Acknowledgments

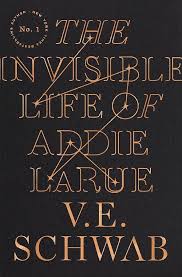

byThe acknowledgments section of this book reveals the author’s complex relationship with storytelling and the exhaustive process of bringing a narrative to life. The author shares a candid glimpse into their personal struggles, including the fear of forgetting those who have supported them along the way. Amidst these challenges, they highlight the integral role of their support system, particularly emphasizing their father’s contribution, who was a sounding board for the initial brainstorming sessions that took place during walks in East Nashville. This passage underscores the author’s apprehension towards the formal act of acknowledgment, driven by a fear of omission caused by a self-admitted poor memory linked to their immersion in the world of books. The author’s reflection on this process is tinged with irony, especially given the thematic focus of the book on memory and its frailties. They confess that writing serves as a means to capture fleeting ideas before they escape, an activity that paradoxically both contributes to and mitigates their forgetfulness. The author’s ambivalence towards acknowledgments, their struggle with memory, and the key support provided by their father, all serve to preface the narrative that follows, providing a glimpse into the personal challenges and influences that have shaped the creation of the book.