Chapter 8 — The beasts of Tarzan

byChapter 8 – The Beasts of Tarzan transports readers into the heart of the equatorial jungle, where danger and defiance collide under a shroud of darkness. A panther prowls with instinctual grace, drawn not by hunger but by something deeper—perhaps loyalty, perhaps vengeance. Its path cuts through thick foliage, eyes glinting under sparse moonlight. Far ahead, the flicker of firelight and the rhythmic beat of drums signal a village preparing for a grim celebration. In one of its huts lies Tarzan, bruised and bound, wrestling not only with ropes but with the thought of his wife and son. The fear isn’t for himself, but for the innocent lives threatened by the malice of Rokoff, whose cruelty knows no restraint.

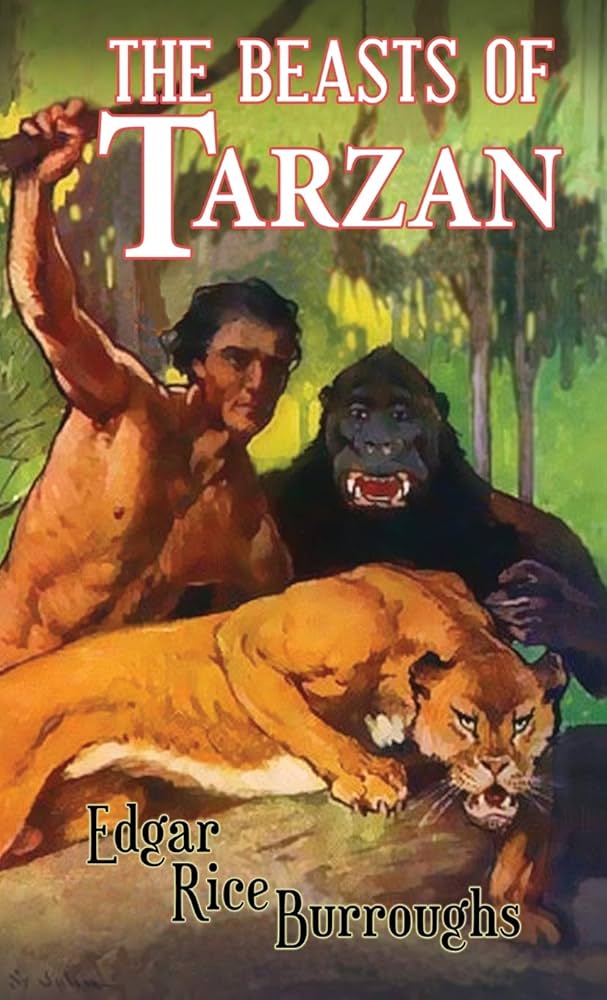

Tarzan’s strength is more than physical; it resides in his unshaken will. Rokoff enters, sneering and smug, flinging cruel words as weapons. He paints vivid images of Jane in peril, feeding Tarzan’s rage and helplessness. Still, Tarzan watches carefully, noting every movement, every mistake. He studies the hut’s structure, the guard’s laziness, and Rokoff’s overconfidence. Despair tempts him, but it never settles. Outside, the jungle holds its breath, waiting for a shift, a sign, a spark. That spark comes when Sheeta, the panther, enters like a shadow made flesh.

The animal does not free Tarzan but kills a native intruder with terrifying ease. Blood stains the earth, and with it, fear blooms among the villagers. Sheeta stands near Tarzan, alert and unmovable. The scene is surreal: a bound man, silent and strong, flanked by a wild beast who chooses to stay rather than flee. This moment of terror halts the sacrifice preparations. Warriors pause, uncertain if they face a man or a myth. Even Rokoff falters, if only briefly, as the illusion of control slips from his grip. The jungle’s primal force has spoken, and it speaks for Tarzan.

As dawn nears, the village stirs with tension instead of triumph. Sheeta’s presence, more powerful than any weapon, keeps the villagers from advancing. Rokoff, desperate to regain authority, urges them forward, but doubt has infected their courage. Tarzan, though still a prisoner, no longer appears defeated. Sheeta’s loyalty reflects a deeper truth—that Tarzan’s connection with the wild is profound, something even the fiercest warriors fear to test. The ritual ceases. Spears lower. The fire crackles in awkward silence. Survival, it seems, may yet favor the man who walks among beasts.

That day, the jungle does not just save Tarzan; it reaffirms the invisible line that divides him from ordinary men. The bond he shares with Sheeta and other wild creatures isn’t born from domination, but mutual respect. Nature responds to Tarzan not as a master, but as kin. This relationship with the untamed world stands in stark contrast to Rokoff’s reliance on manipulation and force. Where Tarzan inspires loyalty, Rokoff commands fear. This chapter subtly explores those differences, making it clear that strength without honor means little in the wilderness.

For readers, this encounter is more than action—it is symbolic. It illustrates how primal forces, when aligned with empathy and instinct, can transcend cruelty and calculated control. In many indigenous cultures, animals are seen as guardians or spirits. Here, Sheeta embodies that belief, not as a mere predator but as an agent of balance. The jungle may be harsh, but it answers to codes more ancient and honest than the schemes of men like Rokoff. In trusting those rhythms, Tarzan becomes more than a man; he becomes a force of nature itself.

This chapter captures the essence of suspense, tapping into themes of loyalty, survival, and the unspoken understanding between man and beast. It teaches that sometimes, rescue doesn’t come in the form of weapons or armies, but through bonds forged in silence and shared struggle. Readers are reminded that power can lie in stillness, and that fear can be broken by presence alone. As Tarzan rises from his lowest point, the narrative swells with renewed energy, propelling him forward toward the battles still to come.