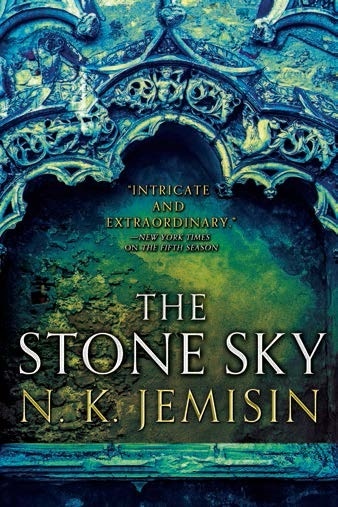

The Stone Sky

Chapter 19: SYL ANAGIST: ZERO

by Jemisin, N. K.The chapter opens with a poignant moment between two ancient beings, Houwha and Gaewha (also called Antimony), who share a complex history as siblings, rivals, and now cautious allies. Their dialogue reveals a sense of nostalgia and unresolved tension, as they reflect on their past names and actions. Gaewha questions whether Houwha regrets their choices, but the response is ambiguous, hinting at deeper layers of guilt and acceptance. The scene underscores their enduring connection amid the weight of millennia, as they prepare to face an uncertain future together.

The narrative then shifts to a reflection on Alabaster’s past, revealing his struggles with societal betrayal and the burden of forbidden knowledge. As a young man, Alabaster initially conformed to the oppressive system of the Fulcrum, but his encounter with an ancient lore cache shattered his complacency. The tablets exposed the cyclical nature of oppression and the lost history of Syl Anagist, leaving him overwhelmed and disillusioned. His temporary breakdown and subsequent punishment highlight the systemic cruelty faced by orogenes, even those of high status, and foreshadow his eventual rebellion.

The chapter further explores themes of awakening and resistance through Houwha’s perspective. After returning from a mission with Kelenli, Houwha’s perception of Syl Anagist’s beauty is tainted by the realization of its exploitative underpinnings. The city’s splendor is revealed as a facade for magical harvesting and control, mirroring the broader societal hypocrisy. When Conductor Stahnyn dismisses Houwha’s request to visit the garden, the interaction underscores the rigid constraints placed on their kind, fueling Houwha’s growing defiance and awareness of systemic oppression.

The chapter weaves together past and present, illustrating the cyclical nature of oppression and the slow, painful process of awakening to injustice. Through Alabaster’s and Houwha’s experiences, it emphasizes the emotional and psychological toll of resisting societal norms, as well as the fleeting moments of solidarity among those who dare to challenge the status quo. The narrative leaves readers with a sense of impending upheaval, as the characters grapple with their roles in a world built on exploitation and lies.

FAQs

1. How does the interaction between Houwha and Gaewha/Antimony reflect the themes of memory and identity in the chapter?

Answer:

The conversation between Houwha and Gaewha (also called Antimony) highlights the fragility and evolution of identity over time. Both characters struggle to recall their original names and past relationships, indicating how millennia have eroded their memories. Houwha notes they were once “siblings, friends, rivals, enemies, strangers, legends,” suggesting identity is fluid and shaped by context. Their exchange—”Was that my name?” “Close enough”—demonstrates how even core aspects of self can become ambiguous. This mirrors the chapter’s broader exploration of how societies and individuals reconstruct or suppress painful histories, as seen in the rewritten stonelore tablets and Alabaster’s crisis of identity.2. Analyze Alabaster’s pivotal discovery of the lore cache and its psychological impact. How does this moment represent a turning point in his character arc?

Answer:

The lore cache revelation shatters Alabaster’s worldview by exposing the cyclical nature of oppression: his people’s subjugation mirrors ancient Syl Anagist’s exploitation of orogenes. Learning that Tablet Three was repeatedly rewritten to erase this history forces him to confront society’s active perpetuation of lies. His flight symbolizes an inability to reconcile this truth with the Fulcrum’s demands, marking his transition from compliance to rebellion. The chapter frames this as a universal struggle—the “false starts” before one “demands the impossible.” Alabaster’s breakdown and temporary return to conformity (siring children, teaching) reflect the tension between resistance and survival, foreshadowing his later radical actions.3. Compare the methods of control used by Syl Anagist (e.g., biomagests, genegineered gardens) with the Fulcrum’s tactics described in Alabaster’s story. What do these systems reveal about power structures in their respective societies?

Answer:

Both systems weaponize beauty and utility to mask exploitation. Syl Anagist’s “sacred, lucrative” gardens—powered by magic-extracting biomagests—parallel the Fulcrum’s manipulation of orogenes’ abilities under the guise of order. The Fulcrum’s “different techniques for highringers” (like psychological manipulation via Guardian Leshet) mirror Syl Anagist’s subtle surveillance (sensors, cameras). However, Syl Anagist’s control is more insidious, embedding oppression in aesthetics (star-flowers winking via magic) and genetics (Stahnyn’s “genocide-failed” features). Both systems commodify life, but Syl Anagist’s integration of oppression into daily life reflects a more advanced, institutionalized form of dehumanization, as noted in Houwha’s newfound awareness of the garden’s true purpose.4. Houwha remarks, “Life is sacred in Syl Anagist—sacred, and lucrative, and useful.” How does this statement encapsulate the chapter’s critique of societal hypocrisy?

Answer:

This line exposes the contradiction between Syl Anagist’s ideals and practices. By framing life as simultaneously “sacred” (moral value) and “lucrative” (economic value), Houwha reveals how systems moralize exploitation. The purple garden, initially beautiful, becomes grotesque once Houwha recognizes its function as a magic-harvesting tool—akin to how orogenes are revered yet enslaved. This parallels Alabaster’s realization that Sanze rewrote stonelore to obscure how society depends on oppression. The chapter argues that such hypocrisy sustains power structures: Syl Anagist’s genegineers and the Fulcrum’s Guardians both weaponize morality (“sacred” life, “order”) to justify extracting value from the subjugated.5. The chapter alternates between Houwha’s present-day reflections and Alabaster’s backstory. How does this structure deepen the narrative’s exploration of cyclical oppression?

Answer:

The juxtaposition creates a thematic echo across time. Houwha’s awakening to Syl Anagist’s exploitation mirrors Alabaster’s discovery of historical lies, emphasizing that oppression reinvents itself. Alabaster’s story shows how systems suppress dissent (rewriting tablets, manipulating highringers), while Houwha’s surveillance (“sensors, cameras”) illustrates how control evolves technologically. Both characters experience disillusionment through education—Alabaster via the lore cache, Houwha via Kelenli’s influence—suggesting awareness is the first step in breaking cycles. The structure implies that resistance is iterative, as seen in Antimony and Houwha’s uneasy alliance, which parallels Alabaster’s eventual rebellion despite his “false starts.”

Quotes

1. “All of us regret that day, in different ways and for different reasons. But I say, ‘No.’”

This exchange between Houwha and Gaewha/Antimony captures the complex legacy of their shared past. The quote reveals how individuals process collective trauma differently, with Houwha’s defiant “No” suggesting a refusal to be defined by regret despite acknowledging its universal presence among their kind.

2. “Some accept their fate. Swallow their pride, forget the real truth, embrace the falsehood for all they’re worth—because, they decide, they cannot be worth much.”

This powerful statement articulates the psychological impact of systemic oppression. It frames a key theme in the chapter about how oppressed people internalize societal falsehoods, serving as a prelude to Alabaster’s personal story of awakening and resistance.

3. “No one really wants to face the fact that the world is the way it is because some arrogant, self-absorbed people tried to put a leash on the rusting planet.”

This indictment of historical power structures reveals the book’s central premise about humanity’s destructive attempts to control nature. The vivid metaphor of “a leash on the rusting planet” encapsulates the chapter’s critique of technological hubris and its lasting consequences.

4. “Life is sacred in Syl Anagist—sacred, and lucrative, and useful.”

This cynical observation marks Houwha’s moment of disillusionment with her society. The triple descriptor exposes the hypocrisy of a civilization that commodifies life under the guise of reverence, showing how economic and magical exploitation corrupts even beautiful things.

5. “They keep such lax security on us, I have noticed. Sensors to monitor our vitals, cameras to monitor our movements, microphones to record our sounds.”

This realization about surveillance underscores the chapter’s themes of control and resistance. The apparent contradiction between “lax security” and comprehensive monitoring reveals how power operates through both visible and invisible means in Syl Anagist.