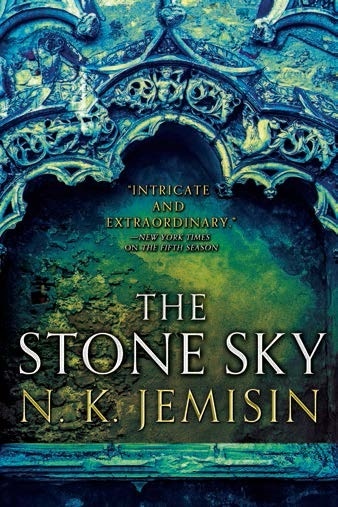

The Stone Sky

Chapter 15: NASSUN, THROUGH THE FIRE

by Jemisin, N. K.The chapter follows Nassun and Schaffa as they board a mysterious pearlescent vehicle called a “vehimal,” which transports them through the earth toward Corepoint. The vehimal’s interior is adorned with elegant gold-like designs and strangely comfortable shell-shaped seats, leaving Nassun in awe of its unknown materials and origins. A disembodied female voice speaks in an unfamiliar yet oddly rhythmic language, which Schaffa partially translates, revealing details about their journey. Nassun is both fascinated and unsettled by the vehimal’s sentient-like behavior, questioning whether it is alive or merely an advanced creation of its long-lost builders.

Schaffa exhibits uncharacteristic restlessness, pacing the vehimal and grappling with fragmented memories of having been there before. His agitation unsettles Nassun, as he struggles to recall the context of his familiarity with the vehicle and its language. His distress hints at deeper, suppressed trauma, contrasting with his usual composed demeanor. Nassun tries to comfort him, but the vehimal interrupts with another announcement, this time directly addressing them and offering to show them something during their transit. The voice’s sudden switch to fragments of their language unnerves Nassun further.

The vehimal transforms part of its wall into a transparent window, revealing a dark tunnel illuminated by rectangular lights. Nassun observes the rough-hewn walls, surprised by their lack of the seamless perfection typical of the obelisk-builders’ technology. The vehimal moves steadily but slowly, leaving Nassun both intrigued and impatient about the six-hour journey. She wonders how such a pace could possibly cover the distance to the other side of the world, and the monotony of the ride begins to weigh on her.

The chapter blends wonder with unease, as Nassun and Schaffa navigate the vehimal’s alien environment. Nassun’s curiosity about the advanced technology is tempered by her fear of its unknown nature, while Schaffa’s fractured memories add a layer of mystery to their journey. The vehimal’s sentient-like interactions and the eerie tunnel visuals create a sense of anticipation, leaving the reader questioning the true purpose of their destination, Corepoint, and the secrets it may hold.

FAQs

1. How does the vehimal’s design reflect the advanced technology of its creators, and what aspects of it unsettle Nassun?

Answer:

The vehimal showcases the obelisk-builders’ technological sophistication through features like self-adjusting shell-shaped chairs with inexplicably soft cushions, golden inlaid designs that may serve functional purposes, and a living, responsive interface that communicates in multiple languages. The vehicle’s organic-mechanical hybrid nature—such as lichen-like carpeting and its ability to transform walls into transparent windows—demonstrates a blurring of boundaries between living creatures and constructed objects. These elements unsettle Nassun because they defy her understanding of nature and technology. The disembodied voice, lack of visible mechanisms, and the vehimal’s apparent autonomy (e.g., translating her unspoken questions) provoke unease, as she cannot reconcile its behavior with familiar systems (e.g., her surprise at hearing Sanze-mat words from a “mouthless” entity).2. Analyze Schaffa’s reaction to the vehimal. What does his fragmented memory suggest about his past and the broader world’s history?

Answer:

Schaffa’s agitation—pacing, touching the golden veins, and recalling fragments of the vehimal’s language—implies he has encountered this technology before, likely during his pre-Fulcrum life. His distress stems from recognizing elements (e.g., the term “vehimal” or the announcement’s structure) but lacking contextual memory, highlighting the damage inflicted by the silver. This suggests the obelisk-builders’ civilization was accessible to humans like Schaffa in the past, either directly or through preserved artifacts. His inability to fully remember underscores themes of lost history and suppressed knowledge in the novel, hinting that the Fulcrum or other powers may have deliberately erased humanity’s connection to this advanced technology to maintain control.3. Why might the author choose to depict the vehimal’s journey as initially slow and mundane, despite its extraordinary capabilities?

Answer:

The slow, almost tedious depiction of the vehimal’s movement through the tunnel serves two narrative purposes. First, it contrasts with Nassun’s awe at the idea of crossing the world in six hours, grounding the fantastical in a relatable human experience (anticipation vs. reality). Second, it builds tension by delaying the reveal of the vehimal’s true speed or purpose, mirroring Schaffa’s fragmented memories and Nassun’s unease. This pacing forces readers to sit with the characters’ discomfort, emphasizing the alien nature of the technology. The mundane details (e.g., the rough-hewn tunnel walls) also subtly critique the obelisk-builders’ priorities—their seamless obelisks coexist with utilitarian infrastructure, complicating Nassun’s assumptions about their perfection.4. How does Nassun’s reaction to the vehimal’s voice differ from Schaffa’s, and what does this reveal about their characters?

Answer:

Nassun reacts with visceral shock and fear when the voice switches to Sanze-mat, instinctively recoiling (e.g., drawing up her feet, imagining insect-like cilia) because she perceives the vehimal as an unknowable, possibly hostile entity. Her orogeny twitching reflexively underscores her youth and conditioned wariness. Schaffa, meanwhile, engages analytically, attempting translation and recalling fragments of language, though his agitation reveals deeper trauma. Their differences highlight Nassun’s inexperience with ancient technologies versus Schaffa’s buried familiarity, as well as their coping mechanisms: Nassun seeks physical comfort (offering Schaffa the chair), while Schaffa grasps for logical understanding despite his pain.5. What thematic significance does the vehimal’s blended organic/mechanical design hold for the novel’s exploration of power and control?

Answer:

The vehimal embodies the obelisk-builders’ mastery over nature and artifice, mirroring the novel’s exploration of how power corrupts through synthesis (e.g., orogeny’s fusion with human bodies). Its “biomagestric storage” and living components suggest a society that harnessed life itself as a resource, paralleling the Fulcrum’s exploitation of orogenes. The vehimal’s polite but detached voice—capable of translation yet indifferent to passengers’ fear—reflects the dehumanizing effects of such control systems. By making Nassun uncomfortable with its ambiguity (is it alive? a machine?), the narrative questions whether advanced power inevitably erodes empathy, a theme echoed in Schaffa’s conditioning and the systemic oppression of orogenes.

Quotes

1. “ALL OF THIS HAPPENS IN the earth. It is mine to know, and to share with you. It is hers to suffer. I’m sorry.”

This opening line sets the haunting, omniscient tone for Nassun’s journey, framing her experiences as both profound and painful. The narrator’s apology foreshadows the hardship to come while establishing a sense of inevitability.

2. “I remember this language… That this … Thing. It’s called a vehimal.”

Schaffa’s fragmented recollection of the ancient vehimal’s language reveals his mysterious connection to the lost civilization that built these structures. This moment highlights the tension between memory and identity that permeates their journey.

3. “I’m not certain the distinction between living creature and lifeless object matters to the people who built this place.”

This philosophical observation captures the chapter’s exploration of advanced technology that blurs the line between organic and mechanical. Schaffa’s remark underscores the alien nature of the obelisk-builders’ creations that Nassun must navigate.

4. “Nassun jumps in pure shock, her orogeny twitching in a way that would have earned her a shout from Essun.”

This visceral reaction reveals Nassun’s lingering trauma from her mother’s harsh training, even as she encounters the vehimal’s unsettling intelligence. The moment connects her past with her present challenges in a single, powerful image.

5. “She finds herself simultaneously fascinated and a little bored, if that is possible.”

This paradoxical observation perfectly captures Nassun’s childlike perspective amid extraordinary circumstances. The line reflects how even world-altering journeys can contain mundane moments, grounding the fantastical elements in human experience.