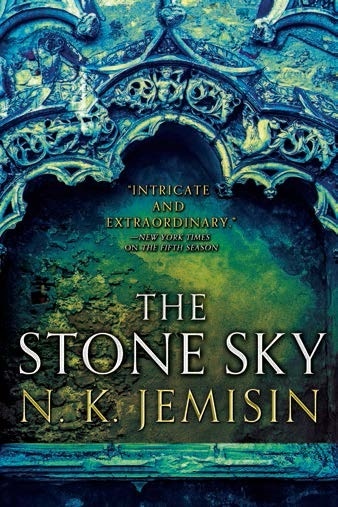

The Stone Sky

Chapter 1: PROLOGUE: ME, WHEN I WAS I

by Jemisin, N. K.The prologue, “Me, When I Was I,” opens with a reflective and fragmented recollection of the past, comparing memories to insects trapped in amber—partial and blurred. The narrator, who feels both connected and disconnected from their former self, describes a world vastly different from the present “Stillness.” This earlier era, called Syl Anagist, is depicted as a thriving, interconnected civilization where the land and climate were unrecognizable compared to the future. The narrator emphasizes the impermanence of change, noting that while the world transforms, it never truly “ends,” only evolves.

Syl Anagist is portrayed as a sprawling, technologically advanced city-nation, its boundaries fluid and its infrastructure interconnected like mold spreading through veins. The cities share culture, resources, and ambitions, functioning as a single entity. The narrator contrasts this unity with the fragmented future of the Stillness, where survival breeds isolation. Syl Anagist’s mastery over nature, architecture, and energy is highlighted, with buildings fused with organic life and vehicles defying conventional physics. The city’s vibrancy and innovation underscore a world unconstrained by scarcity or fear.

Central to Syl Anagist is the amethyst obelisk, a precursor to the garnet obelisk seen in the Stillness. It pulses with energy, anchoring a network of 256 such structures across the land. The narrator describes a hexagonal complex surrounding the obelisk, where a seemingly idyllic prison holds a boy—later revealed to be the narrator’s younger self. The building’s design is deceptive, with beauty masking control, as the inhabitants are conditioned to comply without overt coercion. The sterile, white interior contrasts sharply with the vibrant world outside, symbolizing isolation within a thriving society.

The chapter closes with a focus on the boy, Houwha, who gazes at a garden bathed in the obelisk’s purple light. His colorless appearance mirrors the room’s sterility, yet his presence signifies life amidst artificial constraint. The narrator’s fragmented identity and the boy’s silent observation hint at a deeper story of transformation and loss. The prologue sets the stage for exploring how Syl Anagist’s grandeur gave way to the Stillness, framing the narrative as a meditation on memory, change, and the cost of progress.

FAQs

1. How does the narrator describe their memories, and what does this reveal about their perspective on identity and time?

Answer:

The narrator compares their memories to “insects fossilized in amber,” fragmented and incomplete, with only partial details preserved. This metaphor suggests that while the memories belong to them, they feel disconnected from the person who originally experienced them—”me, and yet not.” This highlights a theme of identity transformation over time, where the narrator acknowledges continuity with their past self but also a profound sense of change. The blurred, jagged nature of the memories also reflects the vast temporal distance between “then” (the era of Syl Anagist) and “now” (the Stillness), emphasizing how time distorts and obscures the past.2. What are the key differences between the world of Syl Anagist and the future Stillness, as described in the prologue?

Answer:

Syl Anagist is portrayed as a thriving, interconnected mega-city with advanced technology (e.g., floating vehicles, living buildings) and boundless ambition, while the Stillness is implied to be a fractured, survival-focused world. Key differences include: (1) Geography—Syl Anagist’s three lands are warmer, with fertile polar regions, whereas the Stillness has expanded ice caps. (2) Sociopolitical structure—Syl Anagist is a unified, expansive civilization, while the Stillness is fragmented into “paranoid city-states.” (3) Technological decay—Syl Anagist’s innovations (e.g., obelisks) are later degraded (e.g., the dying garnet in Allia). The narrator frames this as a decline from grandeur to “miserly dreams” due to the catastrophic Seasons.3. Analyze the significance of the obelisks in Syl Anagist. How might their portrayal foreshadow events in the broader narrative?

Answer:

The obelisks (like the amethyst one described) are central to Syl Anagist’s infrastructure, acting as power sources for its cities. Their “healthy pulse” contrasts with the damaged garnet obelisk mentioned in Allia, hinting at a future decline or corruption of these systems. The fact that they “feed each city and being fed in turn” suggests a symbiotic relationship that could be vulnerable to disruption. Given the narrator’s ominous tone (“if the similarity makes you shiver”), the obelisks likely play a pivotal role in the world’s eventual collapse, possibly tied to the “Seasons” that ravage the Stillness. Their current vitality underscores the tragedy of their later degradation.4. How does the description of the boy (Houwha) and his environment reflect the themes of control and illusion in Syl Anagist?

Answer:

Houwha’s sterile, white prison cell is disguised as a luxurious space with beautiful views, mirroring Syl Anagist’s broader facade of harmony. The lack of guards and the nematocyst-laced windows reveal a society that prioritizes subtle control over overt force—”no need for guards when you can convince people to collaborate in their own internment.” Houwha’s colorless appearance contrasts with the vibrant purple light outside, symbolizing his isolation from the world’s richness. This duality reflects Syl Anagist’s ethos: a utopia built on hidden oppression, where life is “sacred” yet commodified or confined.5. Why might the narrator choose to end the prologue by introducing Houwha, and how does this connect to the chapter’s title, “me, when I was I”?

Answer:

Houwha’s introduction personalizes the narrative shift from world-building to character history, grounding the abstract discussion of Syl Anagist in a specific identity. The title’s paradox (“me, when I was I”) echoes Houwha’s duality—he is the narrator’s past self, yet fundamentally different. By ending with him, the narrator emphasizes the theme of fractured identity across time. Houwha’s trapped existence in Syl Anagist also foreshadows a transformative journey, suggesting that the “end of the world” is intertwined with his personal evolution. This sets up a central question: How does the boy in the white room become the narrator recounting this history?

Quotes

1. “TIME GROWS SHORT, MY LOVE. Let’s end with the beginning of the world, shall we? Yes. We shall.”

This opening line sets the contemplative and urgent tone of the chapter, framing the narrative as both a love letter and a reckoning with time. It introduces the theme of cyclical history and the impending end that permeates the story.

2. “My memories are like insects fossilized in amber. They are rarely intact, these frozen, long-lost lives.”

This vivid metaphor captures the narrator’s fragmented relationship with their past self and the imperfect nature of memory. It establishes the chapter’s exploration of identity and transformation across time.

3. “When we say that ‘the world has ended,’ remember—it is usually a lie. The planet is just fine.”

This powerful statement challenges apocalyptic narratives, emphasizing planetary resilience over human-centric perspectives. It introduces a key philosophical argument about change versus true destruction.

4. “No need for guards when you can convince people to collaborate in their own internment.”

This chilling observation reveals the sophisticated systems of control in Syl Anagist, foreshadowing themes of power and compliance that will develop throughout the story. It’s a profound commentary on institutional manipulation.

5. “Within this sterile space, in the reflected purple light of the outside, only the boy is obviously alive.”

This striking visual contrast between the sterile environment and the living protagonist (the narrator’s past self) encapsulates themes of isolation and the tension between artificial structures and organic life.