Chapter 11: Deafness as a Choice

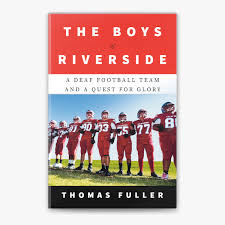

byChapter 11 “Deafness as a Choice”, As summer turned to fall, the Cubs had gained confidence in their skills and their teamwork. They were winning. On the last day of September, halfway through the regular season, the Cubs played another small Christian school, Lutheran High School from La Verne, a city on the eastern edge of Los Angeles County. It was a lopsided game, and at halftime the Cubs were already ahead, 46–0. As the third quarter began, the coaches put in a player who had just joined the team. His name was Dominic Turner, and he stood a little taller than six feet and weighed around 240 pounds, a good deal of it pandemic weight. He had a well-proportioned jawline and brown hair kept in a tight, Ivy League haircut. He had transferred to CSDR a few weeks into the school year and had immediately caught the eye of Keith Adams. Adams wasted no time to make his move.

“You’re kind of a big guy; you would be a good lineman,” Dominic remembers Adams telling him. Dominic told Coach Adams he didn’t like football much. He hadn’t grown up watching it—his grandmother who raised him never had it on—and his previous experience trying to play at hearing schools had been an exercise in alienation.

Keith’s second son, Kaden, the backup quarterback, was also in the gym class, and he joined in the recruitment effort. Pretty soon, the entire gym class was trying to persuade Dominic to join the team. And it worked. Dominic fired off a text to his grandmother: “Pick me up at 6:00 p.m. I’ve joined the football team.”

Dominic had attended seven different schools in his fifteen years of life, but none had quite worked out. He was a good student, generally getting As and Bs, but as a deaf boy in hearing schools he found his social life frustrating. In elementary school he was rarely invited to parties or birthdays or to friends’ homes after school. He was teased because of his deafness.

“They would ask me to say stuff, and then, when I couldn’t say it right, when I couldn’t produce the words right, that was funny to them and they would laugh,” Dominic said. He found himself watching as classmates chatted and played. “I felt so alone. No one was communicating with me at all.”

The best word he found to describe how he felt in those schools was “foreigner.” It was a powerful sentiment considering that he was anything but foreign to Southern California. Born in Riverside, he spent his childhood there and in Mission Viejo, a city not far from the ocean in Orange County.

In the fall of 2021, after California schools had emerged from their COVID lockdowns, Dominic had made the last-minute decision to try CSDR. It would be his second time: he had attended the school as an infant and kindergarten student. Now he was returning, abruptly, desperate to find a place where he felt more at home. He was leaving his hearing school even as his sophomore year was already under way.

In the game against Lutheran, Dominic took his place on the defensive line, crouched down, and put one hand on the turf, set for his first play. It was a pitch to Lutheran’s running back, and as soon as the ball was snapped, Dominic drove the center out of the way and with the help of his fellow lineman Alfredo Baltazar tackled the runner for a loss. Not bad for his very first play in a CSDR uniform. The Cubs went on to win the game, 68–0, and their record improved to 5–0.

After years of searching, Dominic had found his place. Finally, he had this coach and this team where communication wasn’t a problem. The pandemic was still raging in the fall of 2021, and the mood in California was one of frustration. But when a visitor asked Dominic how he was enjoying his football season, he did not hesitate. “Very fun,” he said. “Very, very fun.” He was a “foreigner” in California no more.

Dominic was born profoundly deaf. But later in life his deafness came with an asterisk. At five years old, he underwent an operation to install, under the skin behind his ear, an electronic device known as a cochlear implant. Distinct from hearing aids, which are a set of tiny microphones and speakers that amplify sounds and pipe them into the ear at higher volumes, cochlear implants communicate directly with the brain. They are basically bionic ears. They translate sounds into electrical impulses that stimulate the nerve that connects to the brain stem. The stuff of science fiction only a few decades ago, they allow most deaf people who undergo the operation to hear in varying degrees. For Dominic, whose mother tongue is ASL, which he learned as an infant, the implant gave him a facsimile of hearing and put him in an unusual position. He could switch between the hearing and the deaf worlds at will. He could wake up in the morning and decide whether to have five senses or four. It was something unimaginable to generations before him: it was up to him whether he wanted to hear—or not.

Often, he chose not.

The cochlear implant, a device that would rock the deaf world, was a California invention pioneered by the son of a dentist, William House. House grew up on a ranch in Whittier, a city in Los Angeles County halfway between the coast and Riverside. He attended both dentistry and medical school and was an inveterate tinkerer who seemed to enjoy bucking the medical establishment. He performed one of his first innovations, an experimental surgery to treat the inner-ear affliction called Ménière’s disease, on Alan Shepard, the navy test pilot who in 1961 became the first American in space. Ménière’s can lead to debilitating vertigo, and Shepard’s career had been threatened by bouts of dizziness, tinnitus, and vomiting. When other treatments failed, Shepard secretly traveled to Los Angeles to be treated by House, who at the time was a relatively obscure dentist and researcher publishing papers on his experiments. The surgery was successful, and Shepard went on to join the Apollo 14 mission that lifted off from Cape Canaveral on January 31, 1971, and rocketed to the moon. Shepard became famous for whacking a golf ball using a makeshift six iron in the thin atmosphere on the moon. From space, he spoke to House, who was a guest at Mission Control in Houston. “I’m talking to you through the ear that you operated on!” Shepard said from 230,000 miles away.

At the time of the moon mission, House, already deep into his experiments with cochlear implants, was on the receiving end of heavy criticism. Some doctors believed that sending pulses of electricity through the inner ear could cause irreparable damage. Others simply said the device would not work. One pediatric ear expert was quoted saying there was no “moral justification for an invasive electrode for children.” But House persisted, and in 1984 the Food and Drug Administration approved the sale of his device. It was a crude version of what would come later. Patients reported being able to hear doorbells and car horns and muffled speech, sounds like “that of a radio not completely tuned in,” House said on the day the FDA announced the approval of the implant. But even in its more primitive form, there was a sense that history was being made with this new product. “For the first time, a device can, to a degree, replace an organ of the human senses,” the deputy director of the FDA, Mark Novitch, said at a news conference in Washington when House’s invention was introduced. “Soon a device like this may produce an understanding of speech to many for whom even crude sound would have been considered hopeless just a few years ago.”

Four decades later, implants have to some extent achieved that goal. Richard K. Gurgel, one of the leading researchers in the field of cochlear implants, estimates that around 95 percent of deaf people are candidates for implants and that the technology employed in the devices has improved by leaps and bounds. In many countries, including Sweden and France, deaf children receive cochlear implants almost as a matter of course. Implants can now be equipped with Bluetooth technology so a person can listen to a podcast or receive a phone call that is directly transmitted through the implant to the brain. Although most devices today consist of two pieces—the part that is embedded under the skin and a part that attaches, by magnet, on top of the skin—future models will be fully implanted and thus invisible to other people.

Crucially, however, cochlear devices do not produce what would generally be considered normal hearing. Ann Geers, a developmental psychologist who has been studying cochlear implants for four decades, says a user might hear sounds that are somewhat “muddy” or “underwater.” Users can have difficulties discerning between male and female voices and detecting the nuances of emotion or sarcasm. What a user hears varies enormously from person to person. One objective measurement, distinguishing notes on a piano, illustrated the variability of the implants’ success: In a 2012 study, four out of eleven children with cochlear implants were able to distinguish between a C and a C‑sharp. But one child could not tell a C from an F, and two others heard no difference between a C and an E.

The effectiveness of cochlear implants also depends very much on the setting. Using them in noisy places, like a cocktail party, can be challenging. In 2020, a group of Australian researchers published a scientific review, a meta-analysis of research on the effectiveness of implants in adults. The study found that the quality of the sound that patients were able to hear varied considerably, as did their ability to understand speech. After surgery, patients on average understood 74 percent of sentences read to them in a quiet setting and 50 percent in a noisy environment.

Cochlear implants are clearly imperfect. But thousands of profoundly deaf people use them to interact with the hearing world, whether at jobs or socially. As of 2019, around 740,000 cochlear devices had been implanted worldwide, according to the FDA. In the United States, 65,000 children were fitted with the devices, with each operation typically costing in the neighborhood of $30,000 to $50,000.

For the deaf community worldwide, implants have been a point of debate and controversy. In the early days of their adoption many deaf people were wary of them. They feared the devices would buttress the idea that deaf people needed to be “cured” and that technology could do it. Deafness was not cancer, they argued, not something that needed treatment in the same way a deadly disease does. With sign language, members of the community were fully able to communicate with one another. The prospect of “fixing” deaf children raised questions about the future of an entire culture, of Deaf Culture. For more than a century deaf people had battled for the right to sign-language instruction. They worried what would happen to their language, and to the entire way of life that came with it, if children were urged to accept implants. What if Basque speakers or Navajo speakers were told they were better off getting a device implanted in their brain because their language was too obscure?

In the United States, enrollment in deaf schools, the heart of deaf communities across the country, was falling for a variety of reasons, and the deaf community saw implants as hastening their decline.

The technology bitterly divided families over whether parents should have their deaf children implanted, a tension captured in the 2000 documentary film Sound and Fury, where a deaf couple, Peter and Nita Artinian, decide against providing a cochlear device for their five-year-old daughter, Heather. At one point in the film, Peter Artinian lashes out, “Hearing people think that deafness is limiting, that we can’t succeed. I say, no way!”

Two decades later, the suspicions toward implants have by no means disappeared in the deaf community. But attitudes have softened somewhat. The availability of implants coincided with hard-fought victories for deaf activists in other areas: greater acknowledgment of ASL as a language like any other; the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, which mandated sign-language interpreting for places like hospitals. Technologies like closed-captioned television and the iPhone bridged some of the gap between hearing and deaf communities.

In one measure of the reduced wariness toward implants, five years after Sound and Fury was made, Heather, the girl whose parents had vehemently rejected the device, received one, along with her mother and other deaf relatives. “I just wanted to be able to communicate with the majority of people who live in this world who are hearing,” Heather told a publication at Harvard Law School, where she graduated in 2018.

In a moving speech at Georgetown University, which Heather attended as an undergraduate, she discussed how difficult it was to learn how to speak. After receiving the implant, she had speech therapy classes every day after school, and at first her classmates did not understand her. She sometimes had to rely on sign-language interpreters. But she continued to refine her speech. “I was willing to put in the work and I saw the results,” she said in the Georgetown talk. “I had a wonderful family who supported me through all this,” she said. Some words like “Maryland” and “things” and “human beings” are muffled in her Georgetown speech. For people unfamiliar with her story, it might have been challenging to follow. She spoke about how her roommates asked her to repeat herself “all the time” because they didn’t understand her. But Heather, like Dominic Turner, had forged this uncommon path. They didn’t have to reside exclusively in the hearing world. Or in the deaf world. They just stay in the “middle,” as Heather Artinian called it.

Dominic Turner’s early years with the cochlear implant are testament to the hard work of learning to speak. It was a painstaking journey, and one that left him uncertain for years where he fit in. At the same time, it was a wondrous process that hearing people take for granted. Gaining hearing when he was five years old meant that he had to consciously learn the sounds that he was hearing. His grandmother Joanie Jackson, who raised him, would point out sounds throughout the day.

“Listen! That’s the sound of water,” she would tell Dominic. How else would he know what the trickle of liquid sounded like if it wasn’t pointed out to him? “And that’s a bird. Did you hear it?”

“It was constantly identifying sounds,” Jackson remembered.

For years, this process would require, for Dominic, the concerted study of sound. Even as a teenager, a decade after he received his implant, he found that he needed to concentrate on speech to ascertain it.

“English is a foreign language to me,” Dominic said.

Dominic Turner lives in a world that hearing people might find hard to imagine.

He tunes in to the hearing world when he wants to: At the beach, he likes hearing the sounds of waves. He wears his implants to the movies. He enjoys the roar of certain car engines. But he removes his implant and enters a world without hearing when he is around noises that he finds unpleasant. He dislikes high-pitched voices and people who laugh too loudly. He finds the sounds of traffic rushing past distracting, and in those settings he prefers to hear nothing at all.

At school and on the football field, he keeps the implant off and thrives in the world that he is most comfortable in, signing with his friends and teachers.

Dominic is convinced that when he gets married, it will be to a deaf woman.

Communicating with deaf friends is faster and “more effortless.”

“I just feel that it’s more fun,” he said.