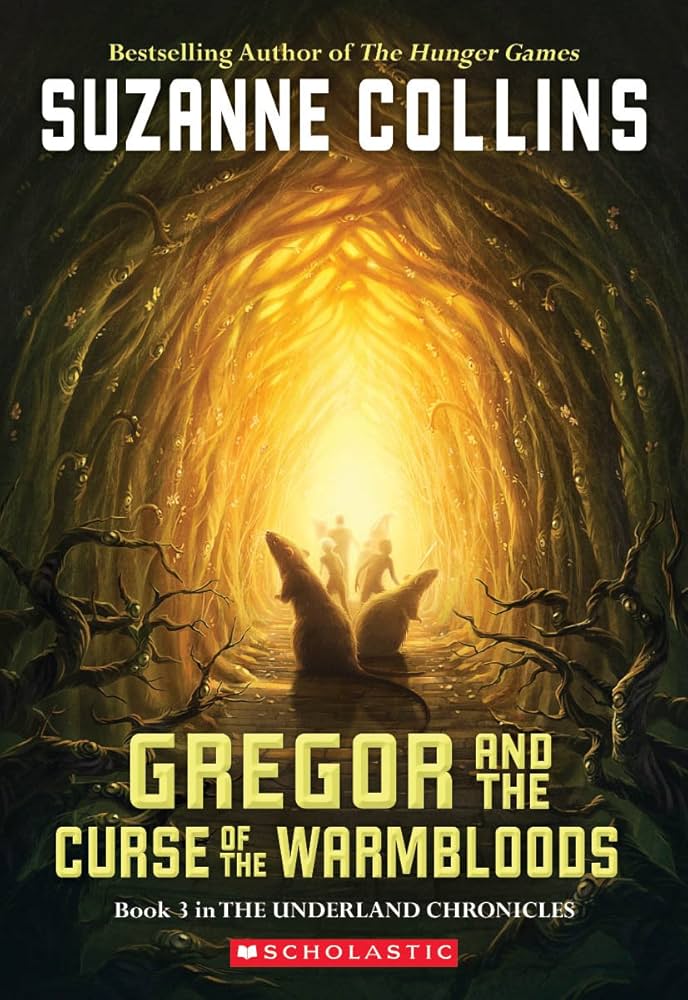

Gregor and the Curse of the Warmbloods

Chapter 12

by Suzanne, Collins,The chapter opens with a tense debate among humans and rats over whether to provide flea powder to the rats as part of their alliance against the plague. Gregor observes the humans’ deep-seated hatred for the rats, as some even prefer death over aiding them. Despite the emotional conflict, the humans reluctantly agree, highlighting the fragile nature of their alliance. The scene underscores the deep divisions between the species, even in the face of a common threat.

The focus shifts to planning the journey to the Vineyard of Eyes, marked by the unveiling of a detailed Underland map. Gregor notices the “occupied” territory, a river formerly controlled by rats but now held by humans, which Ripred had accused them of seizing to starve the rats. Solovet identifies the Vineyard’s approximate location deep in the jungle, near the Firelands, but warns of the cutters—hostile ants—blocking eastern entry. The discussion reveals the logistical challenges and dangers of the quest.

Nerissa surprises the group by announcing she has arranged a guide through a vision, though her credibility is questioned, especially by the mocking rats. Despite skepticism, Gregor publicly supports her, demonstrating loyalty and gratitude for her past help. The rats depart immediately to meet the guide at the Arch of Tantalus, while Gregor prepares for the journey, writing a heartfelt but brief letter to his mother, expressing his determination to find the cure for the plague.

Gregor’s interaction with Mareth, a wounded soldier, adds emotional depth to the chapter. Mareth, still recovering from losing his leg, brings Gregor supplies for the quest, showing his dedication despite his injuries. Gregor reflects on Mareth’s past strength and uncertain future, deepening the theme of sacrifice. The chapter closes with Gregor preparing for the perilous journey, surrounded by allies whose trust and motives remain complex and uncertain.

FAQs

1. What was the main point of contention between the humans and rats at the beginning of the chapter, and what does this reveal about their relationship?

Answer:

The primary conflict was whether to send flea powder to the rats, which the humans reluctantly agreed to after intense debate. This reveals the deep-seated animosity between the species, as evidenced by humans crying and one leaving in protest over helping rats survive. Gregor observes this hatred is “beyond anything in his experience,” showing how historical conflicts and prejudice override their current alliance against the plague. The rats’ survival is seemingly intolerable to some humans, even when cooperation benefits both parties (e.g., the quest to find the cure).2. Analyze the significance of the map in this chapter. How does it deepen our understanding of the Underland’s political dynamics?

Answer:

The map visually represents territorial conflicts and resource scarcity in the Underland. The “occupied” section (formerly rat territory) with a large river highlights the humans’ strategy to starve the rats by controlling their food supply. This aligns with Ripred’s earlier claim about humans weaponizing resources. The color-coded regions also emphasize factional divisions (e.g., fliers, crawlers) and unknown territories, foreshadowing challenges in the quest. The map underscores how geography is politicized, with control over land and resources being central to power struggles.3. How does Nerissa’s introduction of a guide through a vision reflect the tension between prophecy and skepticism in the Underland?

Answer:

Nerissa’s vision-based guide proposal is met with mockery from rats (e.g., Lapblood’s mushroom joke) and muted skepticism from humans. This mirrors the disparity in how Underlanders treat prophecies: Sandwich’s are revered, while Nerissa’s are dismissed despite Vikus defending their partial validity. Ripred’s sarcastic remark about skeletons at the Arch of Tantalus further shows how visions clash with practical concerns. Gregor’s vocal support for Nerissa—contrasting with Ripred’s “you idiot” look—highlights his loyalty but also his naivety about the risks of blind trust in prophecies.4. What does Gregor’s letter to his mother reveal about his character development and the emotional stakes of the quest?

Answer:

The brief, ink-smudged letter shows Gregor’s emotional exhaustion and moral conflict. By framing his decision as “what [his mom] would do,” he justifies his dangerous choice while seeking her approval. The omission of a letter to his dad and his reliance on Vikus to explain further suggests overwhelming guilt and the weight of his family’s suffering. This moment humanizes Gregor, contrasting with his public bravery at the meeting. It also underscores the personal sacrifices driving his participation in the quest—he acts not just for the Underland, but for his plague-stricken family.5. Evaluate Mareth’s role in this chapter. How does his interaction with Gregor foreshadow potential challenges in their upcoming journey?

Answer:

Mareth’s weakened state (labored breathing, crutch use) foreshadows physical limitations during the quest. His thoughtful supply pack (flashlights, batteries) shows his strategic mind adapting to past experiences, but his inability to train or fight as before raises questions about his survival in the jungle. Gregor’s sadness over Mareth’s lost leg hints at the lasting trauma of their previous quests, suggesting emotional and physical vulnerabilities that may resurface. Mareth’s presence also symbolizes the costs of war—once a strong soldier, now struggling with stairs—which may parallel Gregor’s own transformation by the journey’s end.

Quotes

1. “The way they hated the rats — the degree to which they would sacrifice to have them dead — was beyond anything in Gregor’s experience. That guy who had left the meeting, would he really rather see everybody dead than help some rats survive? Apparently, the answer was yes.”

This quote highlights the deep-seated animosity between humans and rats in the Underland, showcasing how prejudice can override even the most practical survival instincts during a plague. It marks a key moment where Gregor confronts the irrational depth of this conflict.

2. “No river, no fish. But now the humans had agreed to give back the fishing grounds so that the rats would go on the quest.”

This passage reveals the political and strategic bargaining between species, emphasizing how control of resources is used as leverage. It underscores the fragile alliance formed out of necessity rather than trust.

3. “Hate warmbloods, the cutters do, hate warmbloods,” said Temp.

This simple yet powerful statement introduces a new threat (the cutter ants) and expands the Underland’s complex web of interspecies conflicts. It foreshadows future obstacles while reinforcing the theme of pervasive hostility in this world.

4. “If I dreamed up this guide, then you will be none the worse than you are at present,” said Nerissa. “The Arch of Tantalus is as good a place to enter the jungle as any.”

Nerissa’s calm defense of her visions demonstrates her quiet strength and strategic thinking. This moment shows her growing agency and the tension between faith and skepticism that runs through their quest preparations.

5. “I’m doing what I think you would do if I were the one with the plague. Trying to find the cure. Please don’t be mad.”

Gregor’s heartfelt letter to his mother encapsulates his moral dilemma and motivation - acting out of love while fearing disapproval. This private moment reveals the emotional core beneath the political and physical battles.