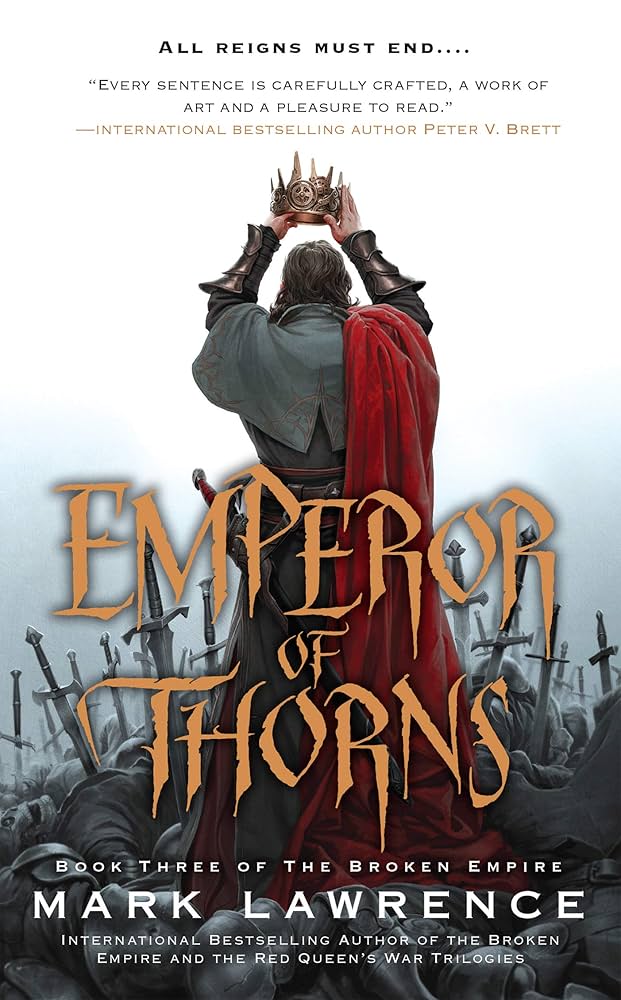

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 9

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with Chella, a necromancer, defeated and trapped in the Cantanlona Swamps, reflecting on her past and her connection to Kashta, a figure from her life who commands her to leave. Their tense exchange reveals Chella’s brokenness and her refusal to be pitied, as well as her lingering anger and power struggles. The scene shifts to her physical struggle in the marsh, where her necromantic powers have been corrupted by natural life, leaving her weakened and in pain. Her desperation is palpable as she curses Jorg Ancrath, the one who has undone her work and forced her back into the realm of the living.

Chella’s physical agony is compounded by emotional torment as a crow, channeling the voice of her deceased brother, taunts her with memories of her past. The crow’s words highlight the irreversible consequences of choosing the necromantic path, a choice driven not by tragedy but by mundane greed and curiosity. Chella resists these memories, but they flood her mind, forcing her to confront the emptiness of her motivations. The crow’s disappearance leaves her alone with her thoughts, emphasizing the isolation and regret that define her existence. Her brother’s teachings, once a source of pride, now serve as a bitter reminder of her fallibility.

As night falls, Chella grapples with the physical and emotional aftermath of her failed necromancy. Her body, now vulnerable to leeches and mosquitoes, symbolizes her return to mortality and the fragility she once scorned. The marsh’s stench and her own weakness amplify her fear, not of the natural world but of the Dead King, a terrifying figure who commands necromancers as servants rather than masters. Chella dreads facing him in her diminished state, realizing her power is now a tattered remnant of what it once was. This fear underscores the shift in her identity from master of death to its subordinate.

The chapter concludes with Chella’s realization that the Dead King’s influence extends far beyond her own cabal, affecting all who delve into necromancy. Her journey, once driven by selfish desires, has led her to a place of subjugation and dread. The chapter paints a vivid portrait of her downfall, blending physical decay with psychological unraveling. Chella’s story serves as a cautionary tale about the costs of power and the inevitability of consequences, even for those who believe themselves beyond reproach. Her struggle to reconcile her past choices with her present reality leaves her trapped between life and death, a prisoner of her own making.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of Chella’s interaction with Kashta/Nuban in her vision, and how does it reflect her internal conflict?

Answer:

Chella’s vision of Kashta/Nuban represents her struggle with identity, power, and belonging. Kashta’s command to “go home” highlights Chella’s rootlessness, as she admits she has no home. Their exchange reveals her unresolved anger and brokenness, particularly when she threatens to enslave him again, showing her lingering desire for control. This mirrors her broader conflict as a necromancer—caught between life and death, power and vulnerability. The fading vision (“Each word fainter and deeper”) symbolizes her weakening grasp on both her past and her necromantic power, foreshadowing her eventual return to painful self-awareness in the marsh.2. Analyze the role of the crow in Chella’s awakening. How does it serve as both a literal and symbolic device in the chapter?

Answer:

The crow acts as a conduit for Chella’s repressed memories and moral reckoning. Literally, it delivers her brother Cellan’s warnings about necromancy’s irreversible consequences, forcing her to confront her past choices. Symbolically, the crow represents death (as a scavenger) and truth (as a messenger), pecking at her denial. Its disappearance—leaving only a feather—mirrors the fleeting nature of her excuses for embracing necromancy. The bird’s mocking tone (“Life is sweet. Taste it”) underscores her forced reconnection with life’s pain and mundanity, contrasting with the grandiosity she once attributed to her dark path.3. How does the chapter portray the theme of “corrupted power” through Chella’s physical and psychological state in the swamp?

Answer:

Chella’s degradation in the swamp embodies the corruption of her necromantic power. Her body, caked in mud and leeches, reflects the decay she once commanded—now turned against her. The “web of necromancy” she wove is “tattered,” paralleling her own unraveling. Psychologically, her memories “like pus from a wound” reveal the rot beneath her power’s facade. Even her pain is ironic: it stems not from her dark arts but from returning to life, highlighting how her pursuit of mastery over death has left her powerless against basic human suffering. The Dead King’s looming judgment further underscores her subjugation to the very forces she sought to control.4. What does Chella’s realization about her motivations for becoming a necromancer reveal about the chapter’s commentary on evil?

Answer:

Chella’s epiphany—that she chose necromancy out of “common greed” and curiosity, not tragedy or poetic darkness—challenges romanticized notions of evil. The chapter critiques banality as the root of corruption: her path began with petty desires (“greed for things”) and the mundane cruelty of “cat-killing” experimentation. This contrasts with her brother’s ominous warnings, suggesting evil often arises from trivial impulses rather than grand damnation. By framing her choice as ordinary weakness, the text implies that true horror lies in how easily humanity can slip into depravity without dramatic provocation.5. How does the setting of the Cantanlona Swamps contribute to the chapter’s exploration of life, death, and rebirth?

Answer:

The swamp is a liminal space where life (leeches, mosquitoes) and death (bog-dead, decay) intermingle, mirroring Chella’s position between worlds. Its “stinking mud” and “foul water” symbolize the impurity of her half-lived existence, while the “memory of blue” in the sky hints at faded vitality. As she crawls from the mire, the setting parallels a grotesque rebirth: her physical suffering (itching, cold, hunger) marks her return to life’s sensory reality. Yet the swamp’s pervasive decay reminds her that her past actions—like the necromantic web “corrupted by frogs and worms”—cannot be fully escaped, complicating any true redemption.

Quotes

1. “After all, that’s what life is. Pain.”

This stark realization comes as Chella lies exhausted in the swamp, feeling the physical and emotional toll of her necromantic powers failing. It encapsulates the chapter’s exploration of the harsh realities of life and death, and how necromancers like Chella distance themselves from the pain of living.

2. “No necromancer truly knows what waits for them as they walk the grey path into the deadlands… If it could be explained to them in advance, shown on one foul canvas, none of them, not even the worst of them, would take the first step.”

Spoken through the crow (channeling Chella’s brother), this quote reveals the fundamental horror and irreversible consequences of necromancy. It serves as a warning about the path Chella chose, highlighting the chapter’s theme of irreversible corruption and the hidden costs of power.

3. “Nothing but common greed: greed for power, greed for things, and curiosity, of the everyday cat-killing kind. Such were the needs that had set her walking among the dead, mining depravity, rejecting all humanity.”

This moment of painful self-reflection shows Chella confronting the mundane, unglamorous motivations behind her descent into necromancy. The quote powerfully contrasts with typical villain origin stories, instead presenting corruption as arising from ordinary human failings rather than grand tragedy.

4. “She felt her heart thump in her chest. Barely more than a child and he had beaten her twice. Left her lying here more alive than dead. Made her feel!”

This quote marks a turning point where Chella fully realizes Jorg Ancrath’s impact on her existence. The physical sensation of her heartbeat symbolizes her forced return to humanity, representing the chapter’s exploration of what it means to be truly alive versus undead.