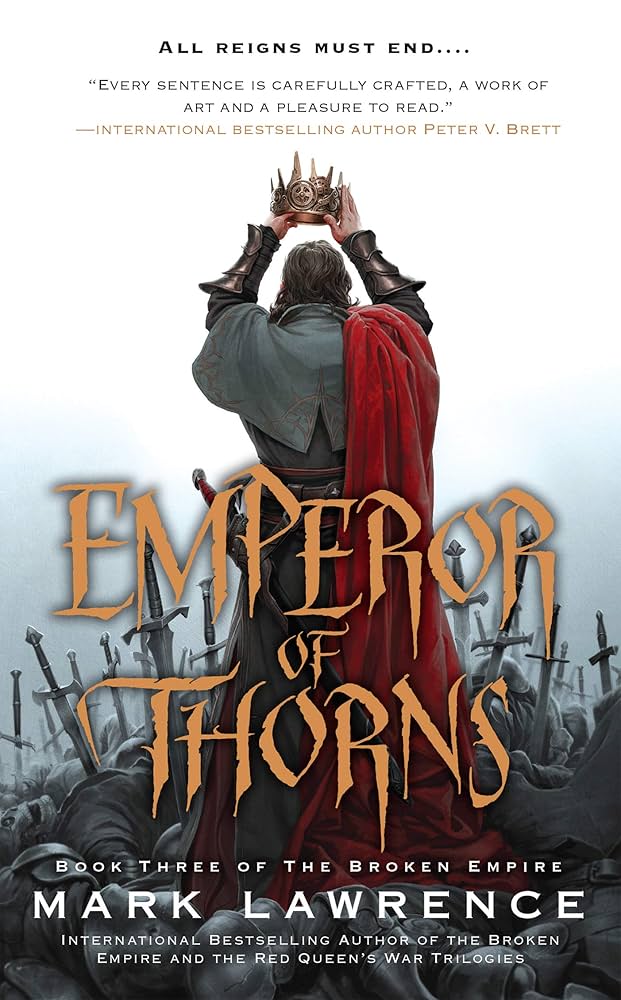

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 8

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with the narrator and Sunny navigating the pre-dawn streets of Albaseat, a city sweltering under the summer heat. The bustling activity of merchants and laborers contrasts with the oppressive atmosphere, setting the stage for the grim encounter that follows. As they pass a smithy, they witness the blacksmith brutally beating his young apprentice, a fair-haired boy reminiscent of the narrator’s brother. The violence escalates, with the smith nearly killing the child, prompting Sunny to intervene reluctantly, while the narrator remains detached, reflecting on the harsh realities of life and his own ambitions.

The narrator’s internal conflict is highlighted as he grapples with his conscience, symbolized by a burning pain across his face. Despite his cynical view that suffering is commonplace, Sunny’s intervention forces him to act. The narrator negotiates with the smith, proposing a contest to buy the boy’s freedom. The smith, confident in his strength, agrees to a challenge involving lifting an anvil, but the narrator outwits him by striking him with a hammer instead, exploiting the lack of rules. The act is pragmatic yet ruthless, underscoring the narrator’s willingness to bend morality to achieve his ends.

After the confrontation, the narrator and Sunny leave the smith and the injured boy behind, the narrator justifying his indifference by claiming the boy would only be a burden. The scene shifts to the crowded plaza near the North Gate, where the chaos of commerce and daily life continues unabated. Sunny expresses doubt about finding their contact in the tumult, but the narrator remains confident, hinting at their next move. The contrast between the earlier brutality and the mundane hustle of the plaza emphasizes the world’s unforgiving nature.

The chapter delves into themes of power, morality, and survival, with the narrator’s actions reflecting his pragmatic and often merciless worldview. His reluctance to save the boy underscores his belief that compassion is a weakness, a lesson learned through past hardships. The encounter with the smith serves as a microcosm of the broader struggles in the narrative, where strength and cunning prevail over empathy. The chapter leaves readers questioning the cost of ambition and the limits of humanity in a harsh, unforgiving world.

FAQs

1. What are the key details that establish the setting and atmosphere in the opening of the chapter?

Answer:

The chapter opens with a vivid depiction of Albaseat at dawn, emphasizing the oppressive summer heat that drives locals to conduct business only in the early hours. The streets are bustling with activity—taverns receiving kegs, women emptying slops, and a smithy already at work. Sensory details like the “grey light before dawn,” the “terracotta tiles,” and the “smell of char and iron” in the smithy create a gritty, lived-in atmosphere. The Horse Coast’s climate and the working-class rhythms establish a harsh, practical world where survival and labor dominate daily life.2. How does the narrator’s reaction to the smith’s abuse of the boy reveal his moral conflict and worldview?

Answer:

The narrator initially rationalizes inaction with cynical detachment (“Boys get kicked every day”), reflecting his hardened philosophy that compassion is a liability. His reference to his brother Will and the “thorns’ tight hold” suggests past trauma influencing his pragmatism. However, his physical pain (the burning across his face) symbolizes a suppressed conscience. His eventual intervention—through manipulation (the contest ruse) rather than direct confrontation—reveals a compromise between self-interest and reluctant empathy. This duality highlights his internal struggle between ambition and residual humanity.3. Analyze the significance of the anvil contest and its outcome. What does this reveal about the narrator’s methods?

Answer:

The proposed contest—holding an anvil overhead—seems like a test of brute strength, aligning with the smith’s worldview. However, the narrator subverts expectations by weaponizing the “no rules” stipulation, striking Jonas with a hammer mid-effort. This mirrors his broader approach: exploiting others’ assumptions to gain advantage without fair play. His tactical deception underscores a recurring theme—that power often lies in unpredictability and psychological manipulation rather than conventional strength. The outcome also reinforces his pragmatic cruelty; he abandons both Jonas and the boy, prioritizing his goals over sustained altruism.4. Compare Sunny’s and the narrator’s responses to the boy’s abuse. How do their differences develop their characters?

Answer:

Sunny’s reluctance (“I should stop this”) and eventual shout reflect a guard’s ingrained duty to uphold order, though his hesitation shows fear of the smith’s violence. In contrast, the narrator’s intervention is calculating—he bargains only when Sunny’s impulsiveness might jeopardize them. Sunny represents conventional morality constrained by self-preservation, while the narrator’s actions are transactional (e.g., offering gold). Their dynamic illustrates contrasting philosophies: Sunny seeks external validation (“The Earl wouldn’t want this”), whereas the narrator operates on self-interest, viewing compassion as a strategic tool rather than a virtue.5. What symbolic or thematic role does the boy’s golden hair play in the scene?

Answer:

The boy’s “fair, almost golden” hair—rare in the south—triggers the narrator’s memory of his brother Will, linking the boy to personal loss. This detail symbolizes the narrator’s buried vulnerability; his pain (“blood in golden curls”) resurfaces physically as facial burning. The hair also contrasts with the grim setting, representing innocence amidst brutality. Yet, the narrator’s ultimate abandonment of the boy reflects his rejection of sentimental attachments, reinforcing the theme that sentimentality is a luxury he cannot afford on his path to power. The imagery ties childhood trauma to his present ruthlessness.

Quotes

1. “Children die every day. Some have their heads broken against milestones.”

This stark observation by the narrator reflects the brutal reality of their world and the moral detachment required to survive in it. It underscores the chapter’s theme of hardened pragmatism versus compassion.

2. “I learned this lesson young, a sharp lesson taught in blood and rain. The path to the empire gates lay at my back. A man diverted from that path by strays, burdened by others’ needs, would never sit upon the all-throne.”

This quote reveals the protagonist’s internal conflict between ambition and empathy, showing how past trauma shapes their ruthless worldview. It’s pivotal in understanding their character’s motivations and moral calculus.

3. “I’ve been told that conscience speaks in a small voice at the back of the mind, clear to some, to others muffled and easy to ignore. I never heard that it burned across a man’s face in red agony.”

This vivid metaphor describes the protagonist’s unusual experience of conscience as physical pain, illustrating their complex relationship with morality. It’s a key moment where we see their internal struggle made manifest.

4. “No rules. You heard him.”

This terse justification for the protagonist’s underhanded victory against the smith encapsulates the chapter’s themes of brutal pragmatism and the rejection of fair play in a harsh world. It’s a defining moment of action that reveals the character’s survival philosophy.

5. “Whatever fire ate at my face I didn’t need another stray, and even if the boy could walk, taking him to the Iberico would be more cruel than another month in Jonas’s care.”

This concluding reflection shows the protagonist’s rationalization of their morally ambiguous actions, balancing cruelty with a twisted form of mercy. It leaves the reader questioning what constitutes true compassion in this brutal setting.