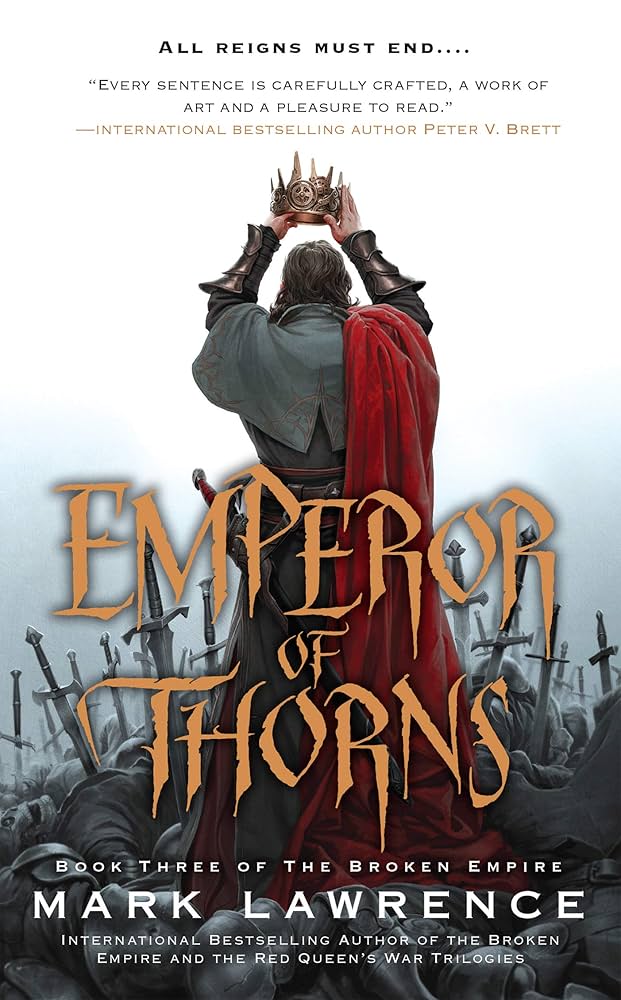

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 55

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter delves into Jorg’s harrowing confrontation with death and the blurred boundaries between reality and dreams. Reflecting on Brother Burlow’s warnings about the seductive yet fatal “light” of dying, Jorg recounts his own experience with this light, describing it as a consuming furnace rather than a gentle dawn. His journey through death is depicted as an endless, cold ocean, where he awaits an angel. This surreal experience culminates in a moment of agony as he finds himself entangled in thorns, symbolizing both physical pain and existential torment. The angel, a figure of salvation, offers him escape, but Jorg remains skeptical, questioning the nature of his reality.

Jorg’s struggle with pain and perception intensifies as he grapples with the idea that his entire life might be a dream. The angel reassures him that all dreams are real, blurring the lines between illusion and truth. This metaphysical dilemma is interrupted by a brutal flashback to his past, where he witnesses his brother William’s violent death. The thorns, emblematic of suffering, become a metaphor for Jorg’s inability to escape his trauma. Yet, through sheer will, he frees himself, crawling toward his brother in a poignant moment of unity, suggesting that their fates are inextricably linked.

The narrative shifts to a chilling memory of Jorg’s father, King Olidan, who forces him to endure the torture of his dog, Justice. This scene underscores Jorg’s internal conflict between self-preservation and loyalty. Despite his fear of fire, he ultimately embraces the flames to comfort Justice, symbolizing his acceptance of suffering and sacrifice. The fire mirrors the “white hunger” of death, a recurring motif that represents both destruction and purification. This act of defiance marks a turning point in Jorg’s understanding of pain and redemption.

In the final section, Jorg reunites with William in a dreamlike afterlife, where they confront the illusion of heaven. Jorg dismisses the golden gates as a human construct, advocating for a deeper, more fundamental truth. Together, they seek a “wheel,” a Builder-made mechanism that holds the key to saving their world from destruction. The chapter closes with Jorg’s determination to turn the wheel, emphasizing themes of brotherhood, sacrifice, and the search for meaning beyond the illusions of life and death. The prose remains stark and visceral, mirroring Jorg’s relentless pursuit of truth amid suffering.

FAQs

1. How does Brother Burlow describe the experience of dying, and how does Jorg’s experience differ from this description?

Answer:

Brother Burlow describes dying as seeing a faint, sweet light that resembles dawn, drawing a person into the “tunnel” of their life. He warns against looking into this light, as it is irreversible and ultimately consumes those who see it. In contrast, Jorg experiences this light as a “cold star” that transforms into a “white hunger,” an incinerating furnace that consumes and then spits him out. While Burlow’s light is portrayed as gentle and inevitable, Jorg’s is violent and cyclical, reflecting his resistance to surrender. This contrast highlights the subjective nature of death and suffering in the narrative.

2. What is the significance of the thorn imagery in this chapter, and how does it relate to Jorg’s character development?

Answer:

The thorns symbolize both physical and psychological torment, representing the inescapable pain that defines Jorg’s existence. When Jorg realizes he has “never left” the thorns, it suggests his entire life has been a struggle against suffering. The thorns’ purpose—”to hurt”—mirrors Jorg’s hardened worldview. His escape by tearing himself free, leaving parts behind, reflects his willingness to endure mutilation for survival. This moment underscores his transformation: he accepts pain as intrinsic to his identity but refuses to be passive, choosing instead to act (e.g., saving William). The thorns thus embody his resilience and fatalism.

3. Analyze the conversation between Jorg and the angel. What does their exchange reveal about the nature of reality and salvation in the story?

Answer:

The angel challenges Jorg’s perception of reality, stating that “all lives are dreams” but “all dreams are real.” This paradoxical idea blurs the line between illusion and truth, suggesting that subjective experience defines existence. Salvation, represented by the angel’s hand, is framed as a choice to end pain—a passive surrender. Jorg rejects this, prioritizing agency over comfort. The scene critiques traditional notions of salvation as external or divine; instead, it implies that meaning is self-determined. The angel’s disappearance (revealed as a Renar soldier) further destabilizes reality, emphasizing Jorg’s isolation in interpreting his own suffering.

4. How does the flashback to Justice the dog contribute to the chapter’s themes of sacrifice and redemption?

Answer:

The flashback to Justice’s burning reveals Jorg’s capacity for love and guilt. Initially, Jorg cannot overcome his instinctive fear of fire to save his dog, mirroring his earlier failures (e.g., abandoning William). His eventual leap into the flames—”I held my dog. I burned.“—signals a pivotal sacrifice, embracing pain to uphold loyalty. This act parallels his later reunion with William and Justice in the afterlife, where he seeks to “save them all.” The scene reframes redemption not as absolution but as active atonement: Jorg must repeatedly confront his past and choose selflessness, even in death.

5. What does the “wheel” symbolize in the chapter’s conclusion, and how does it connect to the broader narrative?

Answer:

The wheel, described as “Builder-made,” represents cyclical fate and the mechanics of the story’s universe. Jorg and William must turn it back to prevent destruction, implying that reality is malleable but requires collective effort. The wheel’s cold, industrial steel contrasts with the golden gates of heaven, suggesting that true salvation lies in confronting harsh truths rather than embracing illusions. By rejecting the gates (“Heaven is over-rated”) and seeking the wheel, Jorg affirms his belief in a deeper, impersonal reality. This aligns with the novel’s themes of agency and the rejection of predestined narratives.

Quotes

1. “‘I’ve heard men say it starts so faint, like a dawn, Brothers. And you look and you find yourself in the tunnel that’s your life, that you’ve walked in darkness all your years.’”

This quote from Brother Burlow captures the chapter’s recurring theme of death as a transformative, almost mystical experience. It introduces the metaphor of life as a dark tunnel, setting the stage for Jorg’s later confrontation with mortality.

2. “‘All lives are dreams, Jorg.’ ‘All dreams are real, Jorg. Even this one.’”

These paradoxical statements from Jorg’s angel represent the chapter’s central philosophical dilemma about reality and perception. They challenge the protagonist’s (and reader’s) understanding of existence, blurring the line between life and illusion.

3. “Nature shaped the claw to trap, and the tooth to kill, but the thorn … the thorn’s only purpose is to hurt.”

This powerful observation about the hook-briar’s thorns serves as both literal description and metaphor for Jorg’s suffering. It reflects the chapter’s exploration of pain as a fundamental, almost purposeless aspect of existence.

4. “‘I don’t know what real really is,’ I said. ‘But it’s deeper than this.’”

This quote marks a turning point where Jorg rejects conventional notions of heaven and afterlife. It represents his existential quest for fundamental truth beyond constructed realities, a key theme in the chapter’s climax.

5. “Save them all, or none.”

This terse declaration encapsulates Jorg’s absolutist philosophy and moral transformation. Coming at the chapter’s conclusion, it represents his rejection of compromise and acceptance of ultimate responsibility, tying together the themes of sacrifice and redemption.