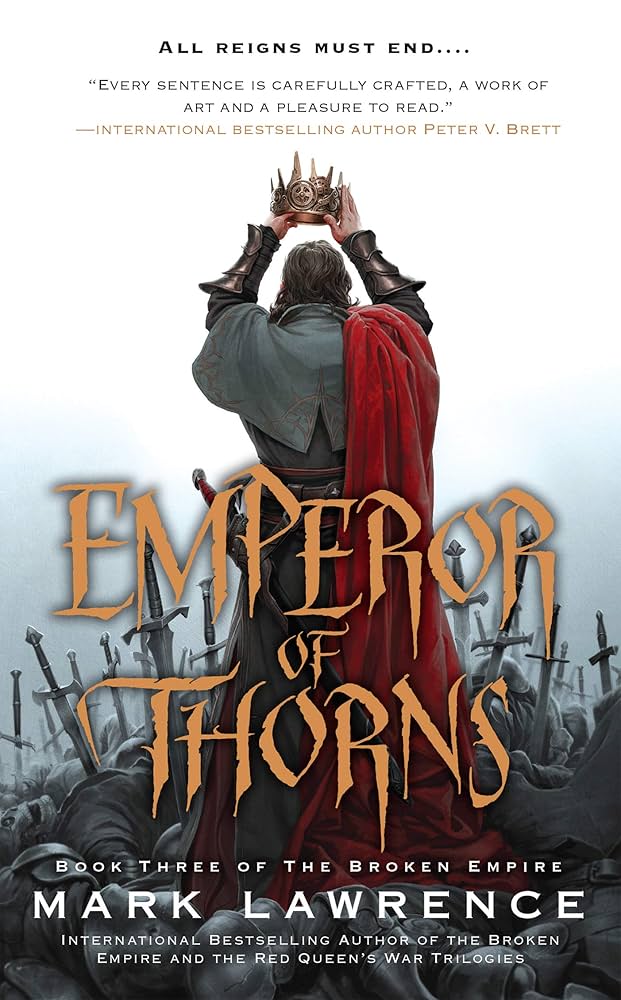

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 50

by Mark, Lawrence,This chapter, ‘Chapter 48’, is rich in content and well worth a careful read.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of the folded parchment Luntar gives to Jorg, and how does it reflect the theme of fate versus free will in the chapter?

Answer:

The folded parchment containing “four words” symbolizes both the knowledge of a predetermined future and the slim possibility of altering it. Luntar, who “sees the future,” acknowledges the unlikelihood of changing fate (“It’s unlikely that we can”) but still encourages Jorg to try (“Not every ending can be seen”). This interaction underscores the tension between destiny and agency—a recurring theme in the chapter. Jorg’s skepticism (“And does it work?”) contrasts with Luntar’s ambiguous guidance, suggesting that while outcomes may be foreseen, the path to them remains fluid. The parchment’s secrecy (“Don’t read them until the right moment”) further emphasizes the precarious balance between foreknowledge and action.2. Analyze the power dynamics in Jorg’s confrontation with Moljon. How does this scene reveal Jorg’s leadership style and political strategy?

Answer:

Jorg’s encounter with Moljon showcases his tactical dominance and psychological acumen. By seizing Moljon’s finger, Jorg demonstrates physical control, but his critique of Moljon’s submission (“you let it be used to separate you from your pride”) reveals a deeper strategy: undermining opponents by exposing their weaknesses to allies. His public humiliation of Moljon (“He hasn’t the strength that’s needed”) serves dual purposes—asserting his own authority while destabilizing potential rival factions. This aligns with Jorg’s later advice to Taproot about breaking factions to absorb their remnants (“Kill the head and the body is yours”). The scene highlights Jorg’s ruthless pragmatism and his ability to turn minor conflicts into opportunities for broader political gains.3. How does the description of the throne room and the Hundred’s interactions reflect the chaotic nature of imperial politics?

Answer:

The throne room’s depiction—with its “hubbub of talking,” shifting alliances (“parties broke off to occupy side chambers”), and superficial engagements—mirrors the disorder of empire-building. The “gaunt” throne, “waiting for a victim,” symbolizes the precariousness of power. Taproot’s explanation of vote-swaying (“special interest – a threat”) underscores how fragmented loyalties and regional blocs complicate governance. The scene’s chaos is heightened by Jorg’s abrupt violence (breaking Moljon’s finger) amid diplomatic maneuvering, illustrating how raw force and negotiation coexist in this political landscape. The Hundred’s behavior reflects a system where power is transactional, temporary, and often performative, as seen in Moljon’s attempt to assert dominance through spectacle (“waving his arms as he spoke”).4. What role does foreshadowing play in the chapter, particularly through Luntar’s prophecies and the triple-goddess imagery?

Answer:

Foreshadowing permeates the chapter, primarily through Luntar’s cryptic warnings (“a future in which we all burn”) and the triple-goddess motif. The latter—comprising the Queen of Red, Katherine, and the Silent Sister—suggests cyclical inevitability (“three generations of the same woman”). This imagery hints at recurring historical patterns or fated roles the characters might fulfill. Luntar’s assertion that Jorg will “just know” the right moment to read the parchment implies an impending crisis, while his admission that not all endings are foreseeable leaves narrative tension unresolved. These elements create a sense of impending doom, priming readers for future confrontations or revelations tied to destiny’s inescapability.5. Evaluate Jorg’s handling of the rumor about the Pope’s death. What does this reveal about his approach to misinformation and reputation?

Answer:

Jorg’s directive to Taproot—to spread or confirm the rumor of the Pope’s death while denying involvement—reveals his manipulative mastery of perception. By controlling the narrative (“if there isn’t such a rumor – start one”), he weaponizes misinformation to destabilize opponents and cultivate an aura of unpredictability. His cavalier tone (“I damn well hope so”) suggests he views reputation as a tool rather than a constraint. This aligns with his earlier actions (e.g., breaking Moljon’s finger to project strength) and underscores his belief in power through calculated ambiguity. The scene also highlights the political utility of chaos, as Jorg leverages rumors to divide factions or test loyalties within the Hundred.

Quotes

1. “‘Not every ending can be seen.’”

This quote from Luntar captures a central theme of fate and free will in the chapter. Despite his ability to see possible futures, he acknowledges the limits of prophecy, suggesting that some outcomes remain unwritten and open to change through action.

2. “‘Why would you hand me a lever to your pain?’”

Jorg’s rhetorical question to Moljon demonstrates his ruthless pragmatism and understanding of power dynamics. This moment reveals his strategic mindset—turning others’ weaknesses into opportunities—while also showcasing his violent charisma as a leader.

3. “‘When they look at a man who calls on favour from caliphs out of the hot sands and norse dukes in their mead halls—they might start to think they see an emperor.’”

Taproot’s analysis highlights Jorg’s political strength—his ability to unite disparate factions. This quote underscores the chapter’s exploration of leadership and perception, showing how Jorg’s unconventional alliances make him a compelling candidate for emperor.

4. “‘You need fifty-one votes only if all votes are cast.’”

This strategic insight from Taproot reveals the political maneuvering at play in Jorg’s bid for power. The quote exemplifies the chapter’s focus on the pragmatic realities of empire-building, where perception and manipulation matter as much as raw numbers.

5. “‘If she lived through that she’s made of sterner stuff than I am.’”

Jorg’s darkly humorous remark about the Pope’s death (or survival) encapsulates his brutal worldview and the high-stakes game he’s playing. This quote represents the chapter’s recurring theme of consequential violence and its political ramifications.