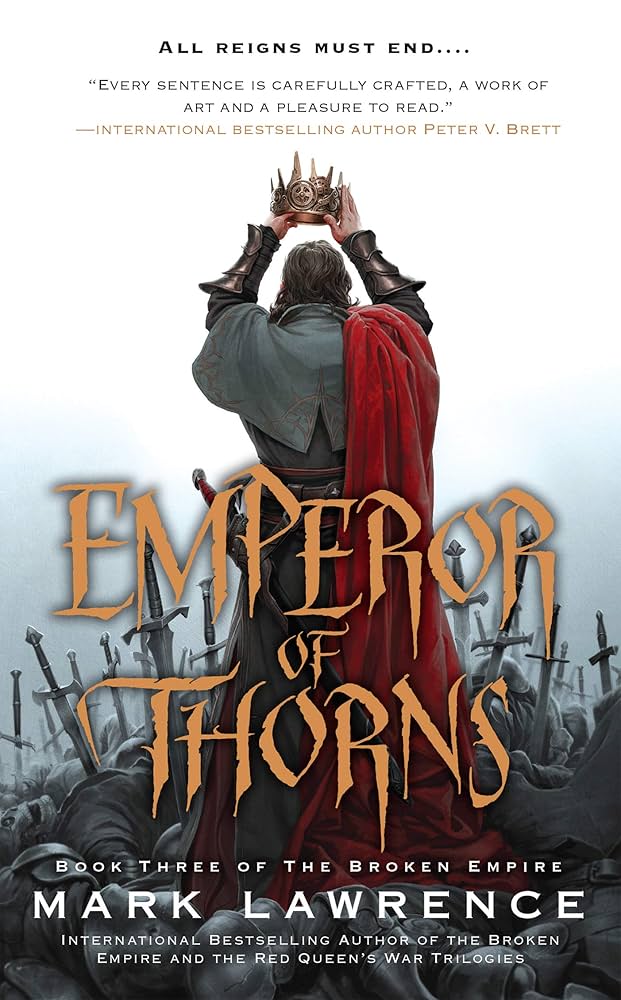

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 42

by Mark, Lawrence,The protagonist rides toward the delegations of Ancrath and Renar, reflecting on his complicated relationships with Katherine and Miana. He acknowledges his flaws and the poor choices he’s made, including his recent encounter with Chella, which he rationalizes as an inevitable act of desire. His companions, Makin and Red Kent, join him, their banter hinting at their shared history and unspoken understanding. The protagonist’s physical wounds and emotional burdens weigh on him as he navigates the tension between his responsibilities and his impulses.

Upon reaching Holland’s carriage, the protagonist engages in sharp exchanges with Katherine and Miana, revealing past conflicts and alliances. The conversation touches on themes of power, survival, and the lingering scars of past battles. Meanwhile, the protagonist observes the devastation wrought by the Dead King’s forces, including the burning of the Tall Castle and the encroaching threat of his undead legions. The sight stirs a mix of anger and helplessness, as he grapples with the loss of his father and the unfinished business between them.

The protagonist’s thoughts shift to his advisors, Coddin and Fexler Brews, who had grand visions of restoring the world to its former state. He dismisses their ideals as impractical, cynically noting that he alone must face the impending crisis in Vyene. The chapter underscores the futility of their prophecies and the protagonist’s resignation to his role in a seemingly doomed world. The weight of leadership and the inevitability of conflict loom large as he contemplates the stakes of the coming confrontation.

As the journey continues, the weather mirrors the grim mood, with cold rain and fog symbolizing the deteriorating situation. The protagonist’s internal turmoil contrasts with the quiet determination of his companions. The chapter closes with a sense of foreboding, as the group nears Vyene, where the final battle—and potential annihilation—awaits. The protagonist’s reflections on fate, power, and legacy underscore the chapter’s themes of inevitability and the harsh realities of leadership.

FAQs

1. How does the protagonist’s relationship with Chella reflect his internal conflict between reason and desire?

Answer:

The protagonist acknowledges that his encounter with Chella was “ill advised,” recognizing it as a dangerous choice driven by primal urges rather than rational thought. He describes how the flesh sometimes overrides intellect, comparing it to the instinct to pull away from fire. This moment highlights his ongoing struggle between calculated decisions and impulsive desires—a theme recurring throughout his life. His admission that “flesh meets fire” suggests a lack of complete self-control, compounded by his awareness that Miana “deserved better,” showing guilt over betraying emotional commitments for physical gratification.2. What strategic concerns arise from the protagonist’s observation of the Dead King’s forces?

Answer:

Through the view-ring, the protagonist observes the Dead King’s legions advancing rapidly toward Vyene, with black sails on the Sane River and columns marching along both shores. He estimates “tens of thousands” of undead soldiers, possibly growing in number, and questions the tactical wisdom of “dead men against heavy horse and city walls.” The observation raises urgent strategic concerns: the horde’s unexpected speed may intercept his delegation before reaching Vyene, and their desecration of Ancrath’s lands—including potentially Perechaise’s graves—carries both emotional weight and implications for the region’s stability. The fires in the Tall Castle further symbolize the irreversible destruction of his past.3. Analyze the significance of the protagonist’s reaction to his father’s rumored death.

Answer:

The protagonist struggles to accept his father’s reported death, insisting it “didn’t fit” because he believed fate destined him to be the one to kill his father. This reaction reveals unresolved trauma and a need for personal closure through vengeance. His statement—”He had been mine to kill, mine to end”—reflects how his identity and life’s purpose were intertwined with this anticipated confrontation. By setting the matter aside as “unpalatable,” he demonstrates emotional avoidance, contrasting with his usual calculated demeanor. The unresolved tension underscores themes of legacy and unfinished cycles in their fraught relationship.4. How do Fexler Brews’ and Michael’s opposing philosophies about the world’s fate reflect larger thematic conflicts?

Answer:

Fexler Brews represents hope for restoration, believing humanity can revert to a pre-magical “normality” by “turning the wheel” of existence. In contrast, Michael’s brotherhood views flesh itself as a disease to be purged by fire, advocating apocalyptic destruction. These philosophies embody the chapter’s central tension between reformation and annihilation. The protagonist’s skepticism—calling Fexler “deluded”—highlights his pragmatic nihilism, yet his journey to Vyene with his son suggests a reluctant engagement with these existential stakes. The conflict mirrors broader questions about whether broken systems (or realities) can be repaired or must be destroyed.5. What symbolic role does the deteriorating weather play as the delegation approaches Vyene?

Answer:

The worsening weather—late autumn chill, persistent rain, and river fog—mirrors the escalating tension and bleak prospects facing the protagonists. The “sapping” cold and mud reflect both physical discomfort and metaphorical weariness as they near their confrontation with the Dead King and the Builders’ apocalyptic plans. The fog’s refusal to lift suggests obscured judgment or fate, while the unrelenting dampness parallels the “dour” transformation of the countryside, foreshadowing the corruption spreading from the Dead King’s influence. This pathetic fallacy underscores the chapter’s themes of entropy and inevitable decay.

Quotes

1. “There are times when we realize we’re just passengers, all our intellect and pontification, carried around in meat and bones that knows what it wants.”

This reflects the protagonist’s philosophical musing on human nature, acknowledging how primal instincts often override rational thought. It captures a key theme of the chapter about the tension between conscious will and biological drives.

2. “Fexler alone had entertained larger thoughts: he alone had believed we might turn back what had been done and spare mankind from a second coming of the fire that he had once brought down upon us.”

This quote introduces the crucial conflict about saving humanity from impending doom. It highlights Fexler’s unique perspective on reversing past mistakes, contrasting with other characters’ more destructive approaches.

3. “If Fexler proved as deluded as Michael had suggested – if he couldn’t change the nature of existence – Vyene would burn and new suns would rise on man’s last day.”

This dramatic statement underscores the high stakes of the narrative, presenting the apocalyptic alternative if Fexler’s plans fail. It serves as a powerful foreshadowing of potential catastrophic outcomes.

4. “Two Ancraths, the wise had said, two to undo all the magic, to turn Fexler’s wheel! A sour smile quirked my lips. They’d better pray […] for there would be just the one Ancrath in Vyene and he’d brought with him no clue as to how to repair a broken empire, let alone a broken reality.”

This quote reveals the protagonist’s self-awareness about his limitations in fulfilling prophecies. It shows his cynical perspective on destiny while emphasizing the overwhelming challenges he faces in restoring order.