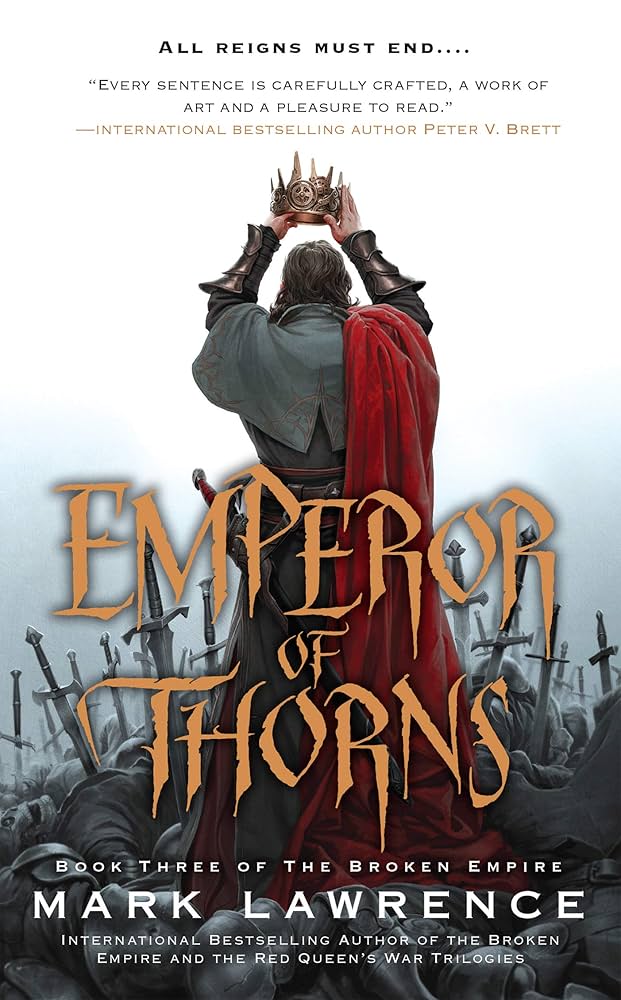

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 37

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with the protagonist reflecting on his encounter with the order of mathmagicians, who no longer seek his death, allowing him to likewise spare them. He contemplates the nature of prophecy, questioning whether the accuracy of soothsayers and mathematicians stems from their intense desire to see the future rather than their methods. This introspection leads him to consider his own desires and whether his willpower might defy their predictions. Meanwhile, he sets aside his thirst for vengeance against Qalasadi, acknowledging that his fondness for the man, rather than moral growth, motivated this decision.

As the protagonist prepares to meet the caliph, Qalasadi and Yusuf accompany him, assuring him that his fate has already been calculated but refusing to reveal the outcome to avoid altering it. The group passes through the mathmagicians’ tower, now missing its front door due to the protagonist’s earlier actions, and observes students attempting to reconstruct it. The journey to the caliph’s palace highlights the stark contrast between the desert’s harshness and the palace’s opulence, with its grand architecture and lack of defensive features, reflecting its purpose for pleasure rather than war.

Upon arrival, the protagonist notes the palace’s lavish design, including towering ebony doors inlaid with gold, symbolizing the caliph’s immense wealth. He feels vulnerable, realizing he is deep in enemy territory with no allies or bargaining power, save for a trick he played in the desert. Qalasadi reassures him that the caliph, Ibn Fayed, is honorable, though not necessarily good. As the doors open, Yusuf hints that the protagonist still has one friend left to make in the desert, leaving him with a cryptic piece of advice before he steps into the throne room.

The chapter concludes with the protagonist walking toward the caliph’s throne, his mind racing with fragmented thoughts and strategies. The tension builds as he prepares to face Ibn Fayed, uncertain of his fate but resolved to navigate the encounter with whatever wit and willpower he can muster. The scene underscores the themes of destiny, power, and the unpredictable nature of human relationships, leaving the reader anticipating the outcome of this high-stakes meeting.

FAQs

1. How does Jorg’s perspective on prophecy and desire evolve in this chapter?

Answer:

Jorg reflects on the nature of prophecy, considering whether the power of desire itself—rather than the methods used—grants soothsayers their insights. He speculates that if his own desire is stronger, he might defy their predictions. This marks a shift from his previous frustration with prophecies favoring Orrin of Arrow. The chapter shows Jorg maturing, as he chooses to set aside vengeance against Qalasadi not out of moral growth but because he genuinely likes the man. This nuanced perspective blends Fexler’s philosophy about desire shaping the future with Jorg’s personal experiences (e.g., “maybe their raw and focused desire delivered their insights”).2. Analyze the significance of the broken tower door and the mathmagicians’ reaction to it.

Answer:

The shattered door symbolizes Jorg’s disruptive nature and his unconventional solutions to obstacles. While the door’s destruction creates a “better puzzle” for the mathmagicians (as Qalasadi notes), it also removes a physical barrier, reflecting Jorg’s tendency to force change through violence. The mathmagicians’ calm acceptance—focusing on reassembling the fragments—highlights their analytical mindset, contrasting with Jorg’s impulsivity. Their dry humor (“I see you found a new solution”) underscores their adaptability and hints at a grudging respect for Jorg’s methods, even as they prioritize intellectual pursuits over brute force.3. What cultural differences between the northern kingdoms and the Sahar are revealed in the description of the caliph’s palace?

Answer:

The palace emphasizes luxury and openness, diverging from northern castles designed for defense. Key differences include:- Architecture: Sprawling, interconnected spaces vs. fortified bottlenecks.

- Art: Absence of statues or ancestral depictions, favoring abstract patterns (e.g., tapestries with “bright colors”).

- Values: The desert’s scarcity makes ebony doors more ostentatious than gold, while northerners prioritize lineage (e.g., “setting down our ancestry in stone”). The palace’s “peaceful” silence and peacock cries contrast with the sterile Builder corridors, reflecting a culture that values harmony with nature over utilitarian efficiency.

4. How does Yusuf’s comment about “friends to make in the desert” tie into the chapter’s themes of choice and fate?

Answer:

Yusuf’s remark underscores the tension between predestination and free will. Earlier, mathmagicians predicted Jorg would make “three friends” in the desert; Yusuf clarifies their sea voyage already counted as one, leaving Jorg agency in choosing the remaining two. This reframes prophecy as flexible rather than absolute, aligning with the chapter’s exploration of desire shaping outcomes. The warning to “choose well” implies Jorg’s decisions—like his audience with Ibn Fayed—will determine his fate, blending the mathmagicians’ calculations with Jorg’s active role in defying or fulfilling them.5. Evaluate the symbolism of the ebony-and-gold doors to the throne room. How do they reflect power dynamics in the Sahar?

Answer:

The doors symbolize Ibn Fayed’s authority through paradox:- Material: Ebony, rare in the desert, signifies wealth more than gold, emphasizing control over scarce resources.

- Scale: Their towering height (“taller than houses”) dwarfs visitors, reinforcing the caliph’s dominance.

- Contrast: The lavish doors precede a “vast and airy” throne room, suggesting power is both displayed and accessible—unlike northern fortresses that hoard security. This mirrors Qalasadi’s description of Ibn Fayed as “a man of honor,” hinting at a ruler who blends opulence with pragmatism, much like the mathmagicians’ balance of prophecy and adaptability.

- Architecture: Sprawling, interconnected spaces vs. fortified bottlenecks.

Quotes

1. “Perhaps for those whose burning desire was to know the future rather than live in the present, perhaps for them it was that desire more than the means they employed that gave them some blurry window onto tomorrow.”

This quote reflects Jorg’s philosophical musing on prophecy and free will, suggesting that the power of desire itself may shape foresight. It captures a key theme of agency versus predestination in the chapter.

2. “The need for vengeance, for retribution against Qalasadi after his attempt on my family, had never burned so bright as the imperative that took me to Uncle Renar’s door. In fact it felt good to let it drop.”

This moment shows Jorg’s character growth as he chooses to release his vengeance against Qalasadi. It represents a significant turning point in his personal development.

3. “And telling you will make the outcome less certain.”

This terse exchange between Jorg and the mathmagicians encapsulates the chapter’s tension around prophecy and knowledge. It highlights the paradox of predictive power - that revealing predictions may alter their outcome.

4. “We became friends at sea, you and I, so you still have a friend to make in the desert. Choose well.”

Yusuf’s parting advice to Jorg serves as both foreshadowing and thematic guidance for the chapter’s conclusion. It emphasizes the importance of choices in determining one’s fate.

5. “The walk from doors to throne, along a silk runner the colour of the ocean, took a lifetime.”

This vivid description captures the weight and tension of Jorg’s approach to meet the caliph. The metaphorical “lifetime” reflects the pivotal nature of this impending encounter for Jorg’s future.