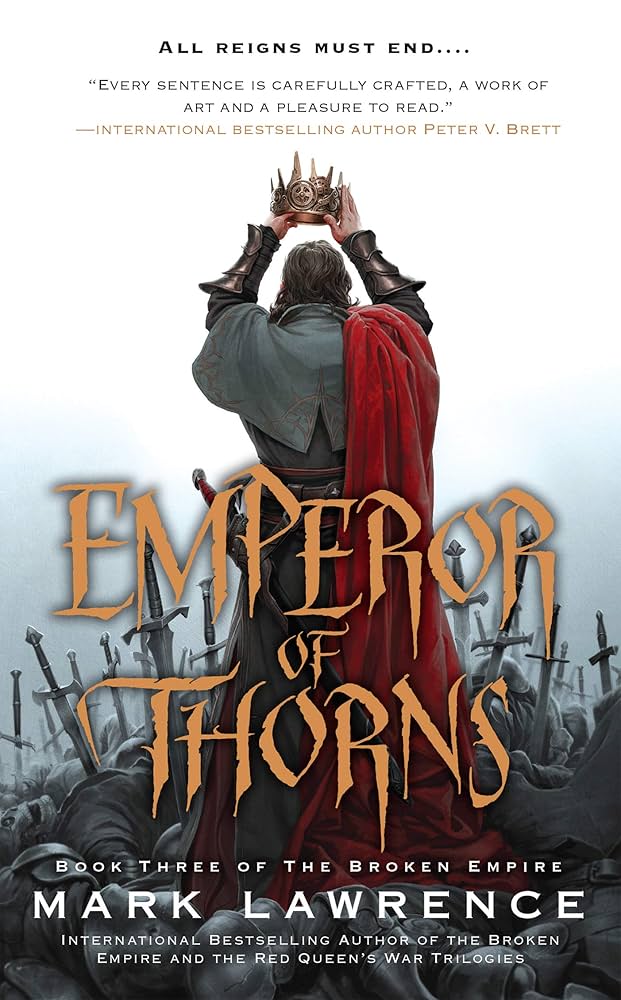

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 36

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with the protagonist and his companions, including Marco and Omal, crossing the Sahar desert from Maroc into Liba, reflecting on the shifting borders and the cautionary tale of “the camel’s nose.” They arrive at Hamada, a city rising from the desert, characterized by whitewashed mud buildings and a hidden aquifer that sustains life. The city’s grandeur becomes apparent as they approach, with towering structures and Moorish-inspired architecture hinting at its wealthy past. The group’s arrival is marked by the camels’ eagerness for water and the bustling activity of the market square, where merchants await their goods.

As they explore Hamada, the protagonist notes the stark contrast between the city’s opulence and his own disheveled state. Marco observes the wealth that has flowed through the region, momentarily dropping his usual sneer. The group hires an old man with a donkey to transport Marco’s trunk to the caliph’s palace, but the protagonist’s unease grows. He reflects on the trap he’s walking into, comparing his situation to Brother Hendrick’s fatal impalement. Despite his fears, he resolves to press on, armed with hidden weapons and a determination for revenge against Ibn Fayed and Qalasadi.

The protagonist and Marco part ways, with Marco heading to the palace to collect a debt from Ibn Fayed, while the protagonist seeks Qalasadi’s tower. The tower, known as Mathema, stands tall and isolated, its smooth surface devoid of easy entry. The protagonist attempts to solve a numerical puzzle on the black crystal door but fails repeatedly. Frustrated, he uses the view-ring, which triggers a dramatic reaction—lightning, humming, and a rising pitch—suggesting the door’s magical nature. The chapter ends abruptly as the door’s transformation intensifies, leaving the outcome uncertain.

Throughout the chapter, themes of revenge, isolation, and the clash between past and present are prominent. The protagonist’s journey is both physical and psychological, as he navigates the desert’s harshness and the political intrigue of Hamada. The tower’s enigmatic door symbolizes the barriers he must overcome, both literal and metaphorical, to achieve his goals. The chapter blends vivid descriptions of the desert city with tense, introspective moments, creating a sense of impending confrontation.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of the saying “beware the camel’s nose” in the context of the chapter?

Answer:

The saying “beware the camel’s nose” refers to a local parable about a camel who gradually encroaches into a tent by begging for small concessions (like sticking its nose in), only to eventually take over entirely. In the chapter, this saying symbolizes the historical erosion of the land between Maroc and Liba, which was gradually consumed until the two realms met in the desert. It serves as a metaphor for how small, seemingly harmless actions can lead to significant consequences—a theme that may parallel Jorg’s own journey, where his incremental decisions (like seeking revenge) could lead to unforeseen outcomes.2. How does the description of Hamada’s architecture and water sources reflect its cultural and historical importance?

Answer:

Hamada’s architecture—whitewashed, rounded mud buildings and grand Moorish-style structures—reflects both practicality and wealth. The whitewash dazzles the eye, protecting against the sun, while the rounded shapes suggest adaptation to wind-swept desert conditions. The presence of water, drawn from a unique aquifer fractured by “an ancient god,” underscores the city’s historical and strategic significance. This water sustains life in the harsh desert, enabling the construction of lavish public buildings like libraries, bathhouses, and galleries. The contrast between humble outer buildings and opulent inner structures highlights Hamada’s role as a cultural and economic hub in Liba.3. Analyze Jorg’s internal conflict as he approaches the caliph’s palace. What does this reveal about his character and motivations?

Answer:

Jorg’s internal conflict reveals his awareness of the recklessness of his quest for revenge. He acknowledges that his plan is flawed (“Sensible hope of revenge… had gone out the window”) and fears imprisonment or death (“the dungeons I would soon rot in”). Yet, he persists, driven by a need to settle debts with Qalasadi and Ibn Fayed. This duality—self-awareness paired with stubborn determination—shows Jorg’s complexity: he is both calculating and impulsive, pragmatic yet bound by personal honor. His toast to Brother Hendrick underscores his fatalistic resolve, as if he sees himself as already impaled by his choices.4. What role does the mathmagicians’ tower play in the chapter, and how does its door mechanism reflect the themes of knowledge and power?

Answer:

The mathmagicians’ tower (Mathema) symbolizes the intersection of arcane knowledge and power in Hamada. Its door, made of black crystal with a numerical puzzle, represents the exclusivity and intellectual rigor required to access such power. Jorg’s frustration with the puzzle (“I didn’t come to play games”) contrasts with his eventual use of the view-ring—a tool of magic—to bypass it. This suggests that true power here is not just brute force but mastery of esoteric systems. The tower’s imposing height and isolation further emphasize the elitism of knowledge, positioning it as a fortress of intellect.5. Compare Marco and Jorg’s attitudes toward Hamada. How do their perspectives shape their respective goals?

Answer:

Marco is initially dismissive but becomes awed by Hamada’s wealth (“Gold has been made and spent here”), which aligns with his goal of collecting a debt from Ibn Fayed—a practical, transactional mission. Jorg, however, views the city through a lens of personal vendetta. His remark about feeling like “the dirty peasant come to court” reveals his outsider status and simmering resentment. While Marco’s journey is about settling accounts, Jorg’s is about confrontation and revenge. Their differing attitudes reflect their broader arcs: Marco as a pragmatic traveler, Jorg as a driven, emotionally charged protagonist.

Quotes

1. “A land of people who would have done well to heed the saying about inches given and miles taken, or as the locals have it, ‘beware the camel’s nose’ after the story of the camel who begs his way by inches into the tent, then refuses to leave.”

This quote introduces a key cultural proverb that foreshadows themes of encroachment and unintended consequences. It reflects the chapter’s exploration of power dynamics and historical erosion of boundaries, setting the tone for Jorg’s own relentless pursuit of revenge.

2. “It’s an unsettling business having to re-evaluate your world view. Neither of us were enjoying it.”

This concise observation captures a pivotal moment where both Jorg and Marco confront their preconceptions about Hamada’s sophistication. The quote exemplifies the chapter’s recurring theme of challenged assumptions and the discomfort of growth.

3. “Now in the midst of a desert that could hold me prisoner on its own, I aimed my path at the enemy’s court, set no doubt just a few score yards above the dungeons I would soon rot in.”

This introspective quote reveals Jorg’s self-awareness about his reckless pursuit of vengeance. It represents a key turning point where he acknowledges the likely consequences of his actions while still choosing to proceed, highlighting the chapter’s tension between fate and free will.

4. “Revenge had brought me here. The need to strike back when struck. Ibn Fayed owed me a debt of blood, but Qalasadi, his debt had a face on it and I would settle that first.”

This declaration crystallizes Jorg’s driving motivation throughout the chapter. The quote is significant for its raw portrayal of vengeance as both a moral imperative and personal compulsion, showcasing the protagonist’s single-minded focus.

5. “Clearly whatever it took to be a mathmagician I wasn’t made of the stuff.”

This self-deprecating remark during Jorg’s attempt to enter the mathmagicians’ tower demonstrates his characteristic blunt honesty about his limitations. The quote serves as both comic relief and meaningful contrast to the chapter’s otherwise intense tone of determination and revenge.