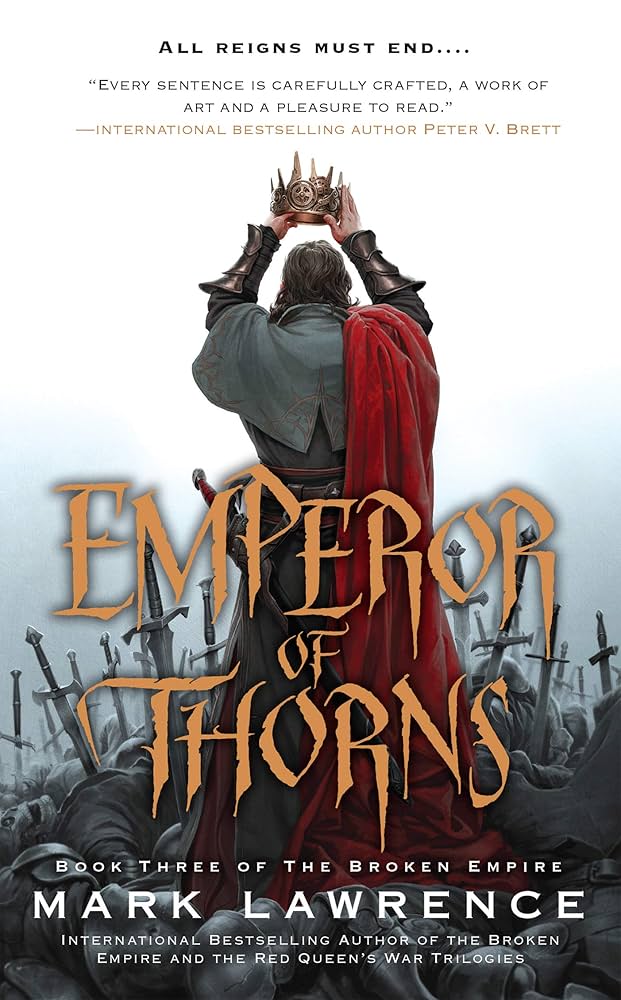

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 20

by Mark, Lawrence,In Chapter 18, “Chella’s Story,” Chella prepares Kai, a young novice necromancer, for an encounter with the Dead King’s court. She warns him to steel his mind and swear any oath demanded of him, emphasizing the gravity of the situation. Despite Kai’s visible fear and weariness, Chella recognizes a latent hardness within him, essential for necromancy. As they walk through the castle corridors, she instructs him to avoid looking at the lichkin, mysterious and terrifying entities that defy conventional understanding of death. Kai’s mix of fear and ambition surfaces, revealing his naivety about the true nature of the Dead King’s power.

Chella explains the distinction between the undead raised by necromancers and the lichkin, which are inherently dead but never lived. These creatures, born from the deadlands, serve the Dead King, who emerged from obscurity to claim his throne. The castle, recently seized from Lord Artur Elgin, is now guarded by reanimated corpses, preserved with chemicals to retain their cunning and strength. Chella notes the Dead King’s pervasive presence, a constant, oppressive force that permeates the castle, bitter and unnerving. The chapter underscores the hierarchy of power in this dark world, where even skilled necromancers like Chella are subordinate to the Dead King.

As they approach the court, the atmosphere grows more ominous. Giant, reanimated freaks and mire-ghouls stand guard, their grotesque forms a testament to the Dead King’s dominion. Chella feels the Dead King’s overwhelming presence, a corrupting force that once drew her in but now feels like a threat. The lichkin’s stench and the ghosts’ eerie glow heighten the tension. Kai, terrified, hesitates, but Chella commands him to stay, knowing escape is impossible. The court’s darkness is pierced by the spectral light of tormented spirits, revealing the lichkin as distortions in reality, their true forms horrifying and alien.

The chapter culminates in the Dead King’s reveal, seated on Artur Elgin’s throne, wearing his robes and body like ill-fitting garments. His smile, crafted from a dead man’s lips, is a grotesque mockery of humanity. Chella’s trembling hands and Kai’s fear underscore the Dead King’s terrifying authority. The scene encapsulates the chapter’s themes of power, corruption, and the unnatural, leaving a chilling impression of a world where death is not an end but a twisted beginning.

FAQs

1. What is the difference between the undead creatures raised by necromancers and the lichkin, according to Chella’s explanation?

Answer:

Chella explains that necromancers typically raise “the fallen” - beings that once lived and died, restoring them to their former flesh and bones under the necromancer’s command. The lichkin, however, are fundamentally different: they are dead entities that never lived as mortal beings. These creatures originate from the deadlands and were never alive in the conventional sense, making them inherently outside human control. The Dead King commands these unnatural entities, while necromancers like Chella can only command reanimated corpses of formerly living beings (as seen with the guards and Artur Elgin).2. How does Mark Lawrence use sensory descriptions to convey the horror of the Dead King’s presence?

Answer:

Lawrence employs visceral sensory imagery to create profound unease. The Dead King’s presence is described as “bitter on the tongue” and felt as “something crawling beneath her skin,” combining taste and tactile sensations. When Chella approaches his court, the lichkin’s stink is compared to ink soaking blotting paper - a sensation that penetrates “bone-deep.” Visual descriptions compound this: ghosts emit a “cold glow” of misery, while lichkin appear as blind spots that distort vision. These multisensory descriptions create a cumulative effect of supernatural corruption that transcends ordinary decay, making the Dead King’s power feel both physically invasive and psychologically inescapable.3. Analyze Kai’s character development in this chapter. What does his reaction to the lichkin reveal about his understanding of necromancy?

Answer:

Kai’s horrified reaction to learning about lichkin (“Christ! Lichkin!”) reveals his naive assumptions about necromantic power. Initially confident in his new abilities after making his first corpse twitch, he assumes necromancers command all dead things (“shouldn’t we be the ones to give the orders?”). This exposes his beginner’s misconception that death is a uniform state to be controlled. His instinctive reach for the knife Chella gave him shows he still relies on physical weapons despite his emerging powers. The chapter marks his transition from arrogance to fearful awareness of the true hierarchy of supernatural forces, where even powerful necromancers serve the Dead King.4. What symbolic significance might Artur Elgin’s repurposed body and throne hold in this chapter?

Answer:

Artur Elgin’s transformed body and appropriated throne serve as potent symbols of the Dead King’s usurpation of mortal power structures. The description of the Dead King wearing Elgin’s well-fitted robes but moving awkwardly in his body suggests a fundamental incompatibility - the conqueror can adopt the trappings of authority but cannot fully inhabit its original form. The driftwood throne, likely crafted from ships Elgin used for raiding, now supports a far more terrifying ruler. This imagery underscores themes of corrupted legacy and stolen dominion, where even a feared pirate-lord becomes a puppet for greater darkness.5. How does Chella’s perception of the Dead King differ between her full necromantic power and her current weakened state?

Answer:

At her peak, Chella perceived the Dead King as a paradoxical “dark-light” or “black sun” - a compelling force whose corrupting radiance paradoxically drew her in while freezing everything it touched. In her weakened state (with “blood pumping once again”), she experiences his presence as pure threat, sculpted from “every memory of hurt or harm or pain.” This dichotomy reveals the Dead King’s dual nature: to the empowered, he represents a dark transcendence; to the vulnerable, only terror remains. The shift also reflects necromancy’s price - what might seem alluring at full power becomes unbearable when grounded in living vulnerability.

Quotes

1. “‘What you’ve seen so far will not prepare you for this. Make a stone of your mind. Swear any oath that is asked of you.’”

This opening warning from Chella to Kai sets the tone for the chapter, foreshadowing the unsettling and transformative experience ahead. It underscores the gravity of entering the Dead King’s realm and the psychological fortitude required.

2. “‘The lichkin are dead – but they never died. It’s given to us to call back what cannot enter heaven and restore it under our command to the flesh and bones it once owned. But in the deadlands, where we call the fallen from, there are things that are dead and that have never lived.’”

This quote defines the eerie nature of the lichkin, creatures that defy conventional understanding of life and death. It introduces a key metaphysical concept in the chapter—the existence of entities that occupy a liminal space between existence and oblivion.

3. “The stink of lichkin hits flesh like ink hits blotting paper: it sinks bone-deep, overriding irrelevances such as the nose. Men are busy dying from the moment they’re born but it’s a crawl from the cradle to the grave. Being near a lichkin makes it a race.”

This vivid description captures the visceral horror of the lichkin’s presence, emphasizing their corrupting influence on life itself. The metaphor of ink on blotting paper conveys how their essence permeates and stains existence irreversibly.

4. “In the fullness of Chella’s necromantic power, when she stepped as far from life as a person can and still return, she knew the Death King’s presence as a dark-light, a black sun whose radiance froze and corrupted but somehow still drew her on.”

This passage contrasts Chella’s past mastery with her current vulnerability, while also personifying the Dead King as an irresistible yet destructive force. The “black sun” imagery encapsulates the paradoxical allure and danger of his power.

5. “He wore Artur Elgin’s body too, and it fitted him less well, hunched and awkward, and when he lifted his head to Chella the smile that he made with the dead man’s mouth was an awful thing.”

The chapter’s closing lines reveal the Dead King’s grotesque inhabitation of a stolen form, culminating in a chilling visual of unnatural control. This moment crystallizes the theme of usurpation—both of bodies and kingdoms—that runs through the narrative.