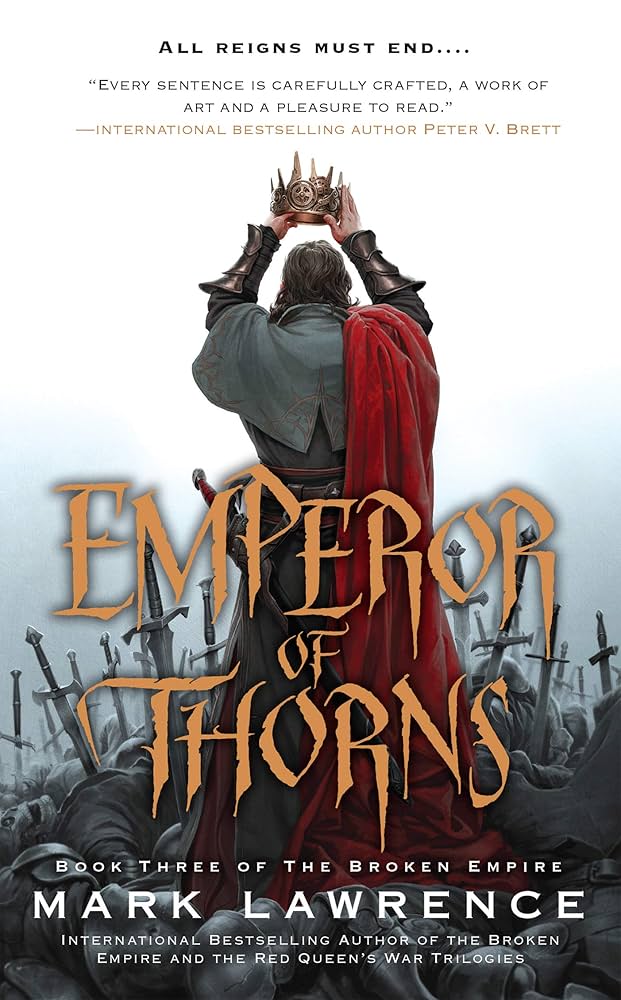

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 18

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with Jorg learning that his father, Olidan Ancrath, is traveling ahead of his own column. Despite his bravado, Jorg feels a deep-seated fear of his father, a sentiment echoed by his companion Makin, who describes Olidan’s unnerving presence and cold demeanor. Though Olidan is less overtly cruel than other rulers, his mere gaze instills dread. Jorg, usually bold, hesitates to confront him, weighed down by old scars and unresolved pain. The oppressive atmosphere—grey skies and a chilling wind—mirrors his internal turmoil as he reflects on his fraught relationship with his father.

Makin shares a poignant story about the death of his young daughter, Cerys, during a petty conflict between neighboring lords. His grief and subsequent quest for vengeance reveal the lasting impact of loss and how it shapes a person. Makin’s journey from a grieving father to a hardened warrior underscores the chapter’s theme of how suffering transforms individuals. Jorg’s attempt to connect with Makin’s pain highlights his own complex emotions, though he struggles to fully empathize, revealing his emotional detachment and latent violence.

As the column marches through Attar’s heartlands, peasants pause their harvest rituals to witness the procession, drawn by the symbolism of empire and the promise of a better past. The scene contrasts the grandeur of power with the simplicity of rural life. Later, Jorg’s wife, Miana, joins him briefly on horseback, her pregnancy adding tension to their journey. Marten, a loyal servant, expresses concern for her well-being, prompting Jorg to reluctantly acknowledge his responsibilities as a husband and soon-to-be father, though his thoughts linger on darker impulses.

The chapter closes with Jorg reentering the carriage, where he informs Miana about his father’s proximity. Their conversation is strained, observed by companions Gomst and Osser, who tactfully avoid intruding. Jorg’s discomfort with familial ties and his unresolved anger toward Olidan simmer beneath the surface, hinting at future confrontations. The chapter masterfully intertwines personal grief, power dynamics, and the weight of legacy, painting a vivid portrait of Jorg’s internal and external conflicts.

FAQs

1. How does the protagonist’s reaction to seeing his father’s carriage reveal his complex relationship with his father?

Answer:

The protagonist experiences a visceral reaction upon seeing his father’s carriage, noting how his “chest ached along the thin seam of that old scar” and feeling an uncharacteristic desire to “let something lie.” This physical and emotional response reveals deep-seated trauma and fear, despite his verbal denial (“I’m not scared of my father”). The contrast between his bold reputation and this moment of hesitation highlights the psychological hold his father has over him. Makin’s observation that Olidan Ancrath “puts the fright in you” with his “cold eyes” further emphasizes how the father’s intimidating presence has shaped the protagonist’s psyche, even as an adult.2. Analyze how Makin’s backstory about Cerys serves as both a parallel and contrast to the protagonist’s relationship with his father.

Answer:

Makin’s tragic tale of losing his daughter Cerys in a violent conflict mirrors the protagonist’s own childhood trauma, showing how both men were shaped by familial loss. However, while Makin channeled his grief into vengeance (tracking down his daughter’s killer), the protagonist’s father directed his cruelty toward his own son. The key contrast emerges when Makin reflects, “you were never as sweet as Cerys, and I was never as cold as Olidan,” underscoring how parental love turned to violence differs from a parent’s failure to love at all. This exchange deepens the protagonist’s self-awareness about his father’s capacity for cruelty.3. What does the peasants’ reaction to the imperial procession reveal about the theme of power in the chapter?

Answer:

The peasants abandoning their harvest work to watch the Gilden Guard highlights power’s seductive spectacle and the lingering cultural memory of empire. The description of empire as “something old and deep, a half-forgotten dream of better things” suggests how power structures manipulate collective hope, even when detached from material reality. This contrasts sharply with the personal power dynamics between the protagonist and his father, showing how institutional and interpersonal power operate differently yet both compel obedience—the peasants through awe, the protagonist through fear.4. How does the protagonist’s internal conflict about Miana’s pregnancy reveal his character development?

Answer:

His conflicted feelings—acknowledging he “should care” more while recognizing a darker part of himself that would welcome violent revenge if harm came to Miana—show his growing self-awareness. Unlike his earlier uncomplicated bloodlust, he now recognizes this duality as problematic. His eventual decision to rejoin Miana in the carriage despite discomfort demonstrates a conscious choice to prioritize familial responsibility over his instincts. Marten’s judgmental gaze acts as a moral compass, pushing the protagonist toward behavior befitting a future father, marking progress in his emotional maturity.5. Evaluate how the chapter uses physical landscapes to reflect psychological states.

Answer:

The “river of mud” and “grey sky” mirror the protagonist’s emotional stagnation when confronting his past. The “cold wind blowing wet from the north” parallels the chilling effect of his father’s presence, while the peasants’ burning fields (“red lines of fire”) symbolize both the destruction in Makin’s past and the protagonist’s smoldering anger. Later, the “fissure in the clouds” allowing sunshine coincides with Miana’s appearance, suggesting hope breaking through his emotional armor. These environmental details externalize internal conflicts, making psychological struggles tangible through the harsh, vivid setting.

Quotes

1. “‘I’m not scared of my father.’ My heartbeat told the lie but only I could hear it.”

This quote reveals the protagonist’s internal conflict about his father, showing how fear manifests physically despite verbal denial. It introduces the complex power dynamics between them that permeate the chapter.

2. “‘That’ is never all there is to it. Hurt spreads and grows and reaches out to break what’s good. Time heals all wounds, but often it’s only by the application of the grave, and while we live some hurts live with us, burning, making us twist and turn to escape them.”

A profound reflection on trauma’s lasting impact, spoken during Makin’s tragic backstory. This encapsulates the chapter’s exploration of how past wounds shape present actions and identities.

3. “‘And how long does it take for a child that you cross nations to avenge, because you couldn’t save her when saving her was an option, to become a child that you knife because you couldn’t accept him when accepting him was an option?’”

This cutting self-reflection draws parallels between Makin’s protective instincts and Olidan’s rejection of Jorg, highlighting the chapter’s theme of cyclical violence and distorted paternal love.

4. “Empire meant something to them. Something old and deep, a half-forgotten dream of better things.”

This observation about peasant onlookers reveals the symbolic power of empire and collective memory, showing how political structures take on mythic significance in people’s imaginations.

5. “I knew that some terrible part of me, down at the core, would have raised its face to the world with a red grin, welcoming the chance, the excuse, for the coming moments of purity in which my revenge would sail upon a tide of blood.”

A chilling self-awareness about the protagonist’s capacity for violence, demonstrating how trauma has shaped his psyche and foreshadowing potential future actions.