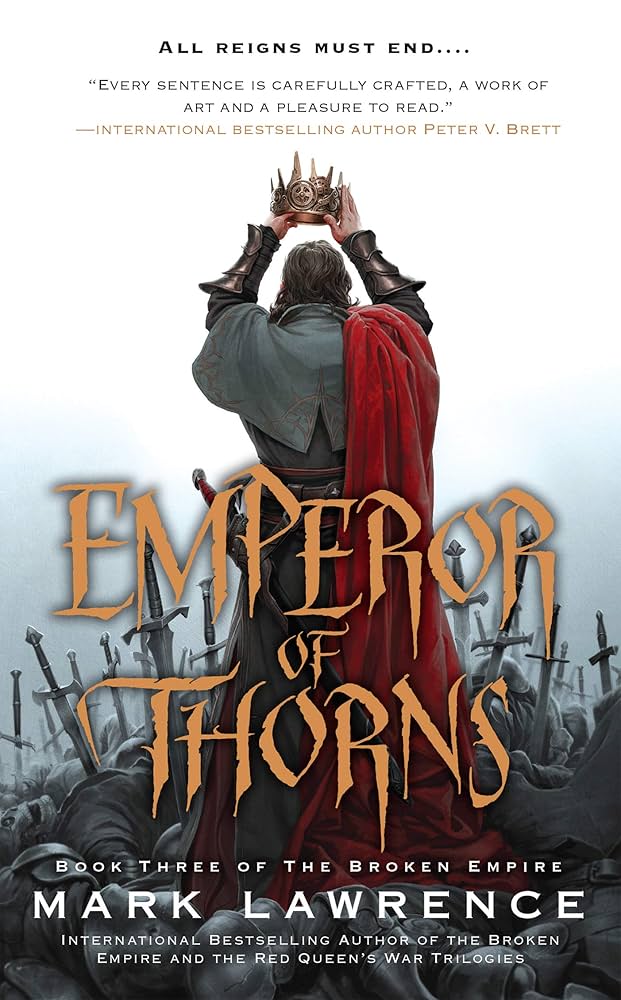

Emperor of Thorns (The Broken Empire, Book 3)

Chapter 16

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with a grim scene where an old woman tortures a man named Sunny, exposing his ribs while a girl named Gretcha presents a strange, oversized scorpion to the narrator. The scorpion emits mechanical sounds, hinting at an unnatural origin, and its eyes briefly flash crimson. Amid Sunny’s screams, the narrator observes the crowd of onlookers, the Bad Dogs, who watch the torture with casual cruelty. The atmosphere is one of brutality and detachment, as the narrator reflects on the inevitability of suffering and the dehumanizing nature of torture.

As the old woman meticulously carves into Sunny’s body, the narrator grapples with fear and despair, attempting to distance himself mentally from the horror. Gretcha continues her violent pursuit of the scorpion, eventually crushing it, while the narrator notices eerie visions in the fire, possibly hallucinations from terror. Sunny’s agony escalates as Gretcha brands him with a hot iron, shattering his teeth and searing his mouth. The narrator, bound and helpless, weeps not for Sunny but out of fear for his own impending torture, realizing the selfish nature of survival in extreme suffering.

The Bad Dogs revel in the spectacle, cheering as Gretcha blinds Sunny with the iron. The narrator’s anger flares, directed at both his captors and the futility of his situation. He recalls a moment with the Nuban, a figure from his past who embraced danger, and yearns for a similar chance to fight back. However, Gretcha hesitates under his intense gaze, and Rael intervenes, securing the narrator’s head before taking the iron himself. The narrator memorizes Rael’s face, determined to remember his tormentor.

Rael taunts the narrator, suggesting his noble status due to the gold and a watch he carries. The chapter ends with tension unresolved, as Rael prepares to brand the narrator, leaving his fate uncertain. The scene underscores themes of powerlessness, brutality, and the psychological toll of torture, blending visceral horror with the narrator’s internal struggle against despair. The mechanical scorpion and eerie visions hint at deeper, possibly supernatural, elements lurking beneath the surface of the narrative.

FAQs

1. What is the significance of the mechanical scorpion in this chapter, and how does it connect to broader themes in the story?

Answer:

The mechanical scorpion discovered by Gretcha represents the lingering presence of advanced Builder technology in the post-apocalyptic world. Its unnatural whirring and clicking sounds, along with its crimson eyes, mirror the description of Fexler’s red star—a recurring symbol of lost technology. This moment underscores the juxtaposition of primitive brutality (the torture scene) with remnants of a more advanced civilization. The scorpion’s mechanical nature also hints at the artificial or constructed elements that may be influencing events, suggesting that even in this violent, lawless world, the legacy of the Builders still exerts an unseen influence.2. How does the author use Sunny’s torture scene to explore the psychology of fear and power?

Answer:

The torture scene meticulously dissects the psychology of fear through the narrator’s dual perspective—both as a potential victim and as someone who has previously been an indifferent observer. The description of Sunny’s mutilation (“This won’t get better. This won’t go away”) emphasizes the irreversible nature of torture, stripping victims of hope and reducing them to “meat and veins and sinew.” The narrator’s terror—alternating between hot rushes and icy dread—reveals how fear dominates even those accustomed to violence. Meanwhile, the Bad Dogs’ casual cruelty (cheering, drinking) illustrates how power dehumanizes both victim and perpetrator, reinforcing the theme that brutality becomes mundane in a broken world.3. Analyze Gretcha’s character development in this chapter. What does her behavior reveal about the cycle of violence in this society?

Answer:

Gretcha embodies the generational perpetuation of violence. Initially introduced as a child excited by her mutant scorpion find, she quickly shifts to active participation in torture—breaking the scorpion’s legs, then wielding the iron to mutilate Sunny. Her “slash of a grin” and obedience to Billan suggest she has been indoctrinated into the Bad Dogs’ culture of cruelty. The moment her smile falters under the narrator’s glare hints at a flicker of hesitation, but Rael’s intervention ensures the cycle continues. Gretcha’s trajectory mirrors the broader societal decay: children are groomed into violence, ensuring its repetition. Her character serves as a microcosm of how savagery becomes normalized.4. How does the narrator’s perspective shift during the torture scene, and what does this reveal about his moral conflict?

Answer:

The narrator oscillates between detachment and visceral fear, attempting to distance himself by pretending to be “in the audience” like his past self—a bystander to suffering. This dissociation fails as he acknowledges the horror of his impending torture. His anger at the “foolishness” of dying in a meaningless camp reveals a deeper existential dread beyond physical pain. Notably, he weeps not for Sunny but for himself, admitting that “at the sharp end of things there is only room for ourselves.” This moment lays bare his moral decay: even as he recognizes the atrocity, his empathy is ultimately self-centered, reflecting the dehumanizing effects of his environment.5. What symbolic role does the Builder’s watch play in this chapter, and how does it contrast with the themes of time and inevitability?

Answer:

The watch, mentioned when Rael confiscates it, symbolizes the inexorable passage of time toward violence and decay. Its precision (“the sound of cogs, of metal teeth meshing”) contrasts sharply with the chaotic brutality of the torture scene, suggesting an indifferent universe where technology outlives humanity’s morality. The scorpion’s mechanical sounds echo the watch, linking both to the Builders’ legacy—a reminder that time moves forward, indifferent to suffering. The narrator’s fixation on memorizing Rael’s face (“one of the last people I’ll see”) underscores this theme: like the watch’s ticking, his fate feels preordained, mechanical, and inescapable.

Quotes

1. “Torture is more than pain and the Perros Viciosos knew it. Certainly the old woman knew it. She hadn’t really begun on him yet, but the mutilation hurt worse than agony that leaves no mark. When the torturer does damage that obviously won’t heal they underscore the irreversibility of it all. This won’t get better. This won’t go away. It lets the man know he is just meat and veins and sinew. Flesh for the butcher.”

This quote captures the psychological horror of torture, emphasizing how irreversible mutilation breaks a person beyond physical pain. It reveals the chapter’s central theme of dehumanization and the cruel artistry of the torturer’s craft.

2. “The strong will hurt the weak, it’s the natural order. But strapped there in the hot sun, waiting my turn to scream and break, I knew the horror of it and despaired.”

This moment marks a pivotal realization for the narrator, who previously accepted cruelty as natural but now experiences its true terror firsthand. It shows the shift from philosophical detachment to visceral understanding of suffering.

3. “At the sharp end of things there is only room for ourselves.”

This brutally concise observation reveals the selfish nature of extreme suffering, where even empathy becomes impossible. It’s a key insight into human psychology under duress, delivered with striking economy of words.

4. “Anger rose in me. It wouldn’t stand before the iron, but for a moment at least it chased away some measure of the fear. Anger at my tormentors and anger at the foolishness of it, dying in some meaningless camp filled with empty people, people going nowhere, people for whom my agony would be a passing distraction.”

This quote shows the narrator’s transition from fear to rage, capturing the existential fury at meaningless suffering. It reflects the chapter’s meditation on the absurdity of cruelty in transient lives.

5. “Are you dangerous? I had asked the Nuban when they held the irons over him. I’d given him his chance, loosed one hand, and he had seized it. Are you dangerous? Yes, he had said, and I told him to show me. I wanted that chance now.”

This callback to earlier events reveals the narrator’s desperate hope for agency amid powerlessness. The repeated question becomes a powerful motif about the nature of true danger and resistance.