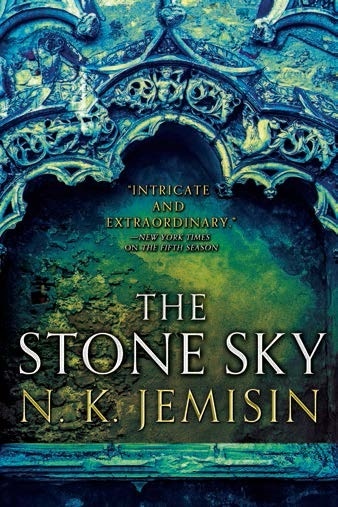

The Stone Sky

Chapter 13: SYL ANAGIST: TWO

by Jemisin, N. K.The chapter follows a group of genetically engineered beings as they explore a luxurious house and garden in Syl Anagist, guided by their enigmatic leader, Kelenli. The house, with its vibrant colors and comfortable furnishings, starkly contrasts their sterile, prison-like living quarters, prompting the narrator to question their own existence for the first time. During their journey to the house, they encounter hostility from a man who views them as abominations, highlighting the prejudice they face as constructs. Kelenli remains composed, but the incident leaves the group unsettled and acutely aware of their outsider status in this “normal” world.

The garden behind the house offers a sense of freedom and wonder, with its wild, imperfect flora and tactile pleasures like springy lichens and fragrant flowers. The group revels in these new sensations, their emotions heightened—Gaewha fiercely claims flowers, others engage in playful or curious activities. The narrator, however, is fixated on Kelenli, grappling with unfamiliar feelings of admiration and longing, which they tentatively label as love. This emotional intensity surprises them, as they had previously believed themselves above such human-like passions.

Kelenli leads them to a small stone structure in the garden, which reveals her personal space—a stark contrast to the opulent main house. The presence of books, a hairbrush, and other personal items suggests a life of autonomy and learning, deepening the narrator’s fascination. Kelenli shares a cryptic revelation about her upbringing with Conductor Gallat, hinting at her role as a “control” in an experiment and alluding to her mixed ancestry. This disclosure sparks a moment of realization for the narrator, though Kelenli’s somber tone suggests darker truths remain unspoken.

The chapter underscores the group’s growing awareness of their own otherness and the complexities of their existence. Through their interactions with the city, its people, and Kelenli, they confront emotions and societal biases they had never before considered. The narrator’s introspection and Kelenli’s layered identity serve as catalysts for their evolving understanding of self, belonging, and the harsh realities of Syl Anagist’s world.

FAQs

1. How does the narrator’s perception of their own identity change throughout the chapter?

Answer:

The narrator begins with pride in their engineered existence, viewing themselves as carefully crafted constructs. However, exposure to Syl Anagist’s “normal” society triggers an identity crisis. The contrast between their sterile, white chamber and Kelenli’s vibrant home makes them question if their existence is prison-like. The hostile encounter with the Sylanagistine man and the fascination with ordinary objects (flowers, scissors) deepen their sense of alienation. By the chapter’s end, they grapple with newfound emotions—love, envy, and self-doubt—realizing their arrogance in assuming they were “above” such human intensity (e.g., “I thought us above such intensity of feeling”).

2. Analyze the significance of Kelenli’s garden house versus the main house. What does this reveal about her character?

Answer:

The main house, though luxurious, feels impersonal (“a museum”), while the garden house reflects Kelenli’s true self. Its imperfections—ivy-covered walls, scattered books, a hair-filled brush—show her rejection of Syl Anagist’s engineered perfection. The space symbolizes autonomy: she chooses its simplicity despite having access to opulence. The narrator notes this is her home, not a cell, emphasizing her defiance of systemic control. Her possessions (books, brush) hint at hidden layers—literacy, self-care—contrasting with the constructs’ lack of personal items. This duality mirrors her role as both insider and outsider in Syl Anagist’s hierarchy.

3. How does the chapter use sensory details to highlight the constructs’ alienation from society?

Answer:

Sensory contrasts underscore their otherness. Visual cues dominate: the “green and burgundy” walls clash with their white chambers; “imperfect” garden flowers contrast with genetically engineered ones. Tactile experiences—springy lichens, soft furnishings—are novel, emphasizing their deprived upbringing. Auditory shifts matter too: the angry man’s shouts and the constructs’ switch to verbal (not earthtalk) communication show adaptation struggles. Most poignant is the stale air of the main house versus the garden’s fragrances, mirroring their emotional awakening—dry confinement versus the “wild” vitality they crave but cannot fully claim.

4. What thematic role does the encounter with the hostile Sylanagistine man play?

Answer:

The man embodies societal prejudice, exposing Syl Anagist’s deep-seated bigotry. His accusations (“mistakes,” “monsters”) reveal a historical narrative painting constructs as inhuman threats, despite their intentional creation. Kelenli’s dismissive response (“He’s Sylanagistine”) suggests this hatred is systemic, not personal. The incident forces the narrator to confront their place in society—both as feared and as naive (e.g., not recognizing danger until guards intervene). This moment catalyzes their emotional turmoil, illustrating how oppression operates through dehumanization and violence, even in an advanced civilization.

5. Why might the narrator describe their newfound emotions as “love,” and what irony does this reveal?

Answer:

The narrator labels their obsession with Kelenli as “love” because it’s the only framework they have for intense emotion, despite its inaccuracy. This “love” blends envy (“I want to be her”), admiration, and a craving for validation. The irony lies in their engineered design: they were meant to be emotionless tools, yet they exhibit profoundly human feelings. Their fascination with Kelenli’s autonomy and beauty mirrors a child’s first crush, highlighting the failure of their creators’ control. This “love” becomes a rebellion—a natural impulse defying their artificial origins.

Quotes

1. “Nothing is hard and nothing is bare and I have never thought before that the chamber I live in is a prison cell, but now for the first time, I do.”

This quote marks the narrator’s first realization of their oppressed existence, contrasting the luxurious freedom of Syl Anagist’s normal citizens with the sterile confinement of their constructed life. It captures the chapter’s theme of awakening to systemic injustice.

2. “With every glimpse of normalcy, the city teaches us just how abnormal we are.”

A poignant reflection on how societal norms reinforce otherness. The narrator recognizes that their engineered origins make them targets of fear and hatred, despite their pride in their creation.

3. “I decide that what I’m feeling is love. Even if it isn’t, the idea is novel enough to fascinate me, so I decide to follow where its impulses lead.”

This vulnerable admission shows the narrator’s first experience of complex human emotion, representing their growing humanity beyond their designed purpose. The uncertainty reflects their evolving self-awareness.

4. “This little garden house, however, is … her home.”

A powerful contrast to the opulent main house, revealing Kelenli’s true belonging. This physical space symbolizes resistance and authenticity amidst the constructed reality of Syl Anagist’s hierarchy.