Chapter 37

byIn Chapter 37 of The Art Thief, we dive deep into the emotional complexities faced by Anne-Catherine and Stéphane Breitwieser, whose relationship is marred by betrayal, disappointment, and personal turmoil. Anne-Catherine, speaking to Swiss art detective Von der Mühll, opens up about her lingering sense of betrayal. She reflects on her relationship with Breitwieser, admitting that she feels he treated her as nothing more than an object, a part of his journey that he discarded when no longer necessary. This painful realization marks the emotional end of their time together in late 2005, but the story doesn’t end there. Breitwieser, seemingly unaffected by the breakup, quickly moves on, finding a new partner in Stéphanie Mangin, a nurse’s assistant who, coincidentally, shares striking similarities to Anne-Catherine. The two bond almost immediately, and shortly after, Breitwieser makes the decision to move in with Stéphanie in Strasbourg, creating a sense of stability that he hasn’t experienced in years.

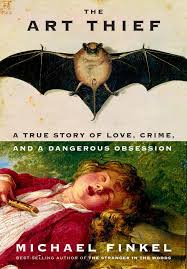

With a renewed sense of optimism and purpose, Breitwieser starts to rebuild his life. His fortunes appear to turn when he lands a significant deal with a publishing company, which pays him over $100,000 for a ten-day interview. This interview leads to the publication of his memoir, Confessions of an Art Thief, where he openly shares the intricacies of his life as an art thief. As part of this reinvention, he announces his new career goals, aiming to pivot to becoming an art-security consultant. Breitwieser dreams of offering museums and private collectors affordable and efficient security solutions, such as enhanced display cases and advanced motion sensors, hoping to erase his criminal past and find acceptance in legitimate work. This new vision for his future brings him a sense of hope, leading him to believe that he could leave behind the shadows of his past and make a meaningful impact in the art world as a trusted consultant.

Unfortunately, despite his best efforts, Breitwieser’s return to a more normal life proves to be short-lived. The complacency that comes with newfound confidence leads him to make a critical mistake. Emboldened by the success of his book and the attention it brings, Breitwieser decides to commit another crime. While at the airport in Paris, he steals items from a boutique, an impulsive act driven by the thrill of defying the law. However, things quickly spiral out of control when he miscounts the number of undercover security guards present, leading to his swift arrest. The legal consequences are minor—an overnight stay in jail and a sentence of community service—but the damage to his public image is severe. Critics begin to mock him, and his dreams of becoming a respected consultant fall apart. His reputation is tarnished, and he is forced to retreat to Stéphanie’s apartment, where feelings of isolation and worthlessness consume him. Unable to secure legitimate work, Breitwieser sinks into a state of despair, unable to escape his past actions.

In an act of desperation to regain a sense of connection with art, Breitwieser steals a painting by Pieter Brueghel the Younger at an antiques fair in Belgium. He places the valuable landscape painting in Stéphanie’s apartment, hoping that it will bring him a sense of fulfillment, if only momentarily. Unfortunately, Stéphanie soon discovers the origins of the painting and is horrified by the extent of Breitwieser’s actions. Feeling betrayed and compromised by his criminal behavior, she ends their relationship, unable to overlook his transgressions any longer. In a final act of betrayal, Stéphanie contacts the authorities and provides them with the evidence needed to bring Breitwieser to justice once again. This marks the tragic conclusion to his journey, where his repeated failures to break free from his criminal past lead to yet another arrest and the complete collapse of the life he had tried to rebuild. This chapter serves as a poignant reminder of the consequences of one’s actions and the inability to escape the repercussions of a life built on deception and crime.