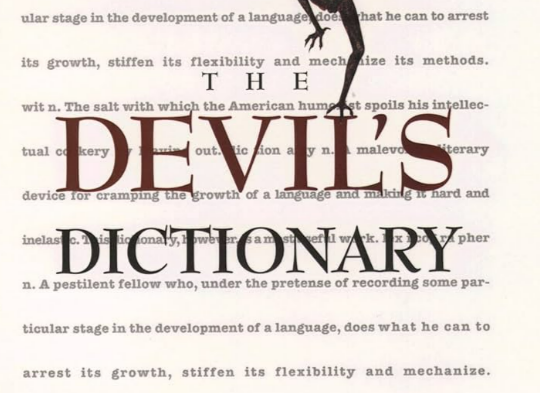

The Devil’s Dictionary

Chapter D

byChapter D sets the tone with the redefinition of Damn, a word that Bierce cleverly allows to shift in meaning depending on who defines it—be it theologian, philosopher, or common man. This ambiguity allows him to satirize how language, especially in moral contexts, is shaped more by perception than principle. Bierce uses the term to mock not just religious doctrine, but the human tendency to tailor judgment for convenience. Through this lens, condemnation becomes a flexible tool used selectively. His wit reveals how moral language often serves personal bias rather than universal truth.

With Dance, Bierce combines celebration and subversion. He frames it as both a form of joy and a subtle rebellion against social restraint. While outwardly innocent, dance in his view often masks flirtation or impropriety—highlighting the fine line between culture and indulgence. The definition underscores how physical expression can be a form of coded communication, especially in societies that restrict open dialogue. His commentary invites readers to consider how cultural practices reflect deeper desires that decorum tries to suppress.

Danger becomes a study in courage—or the lack thereof. Bierce defines it as something we claim to face head-on but often ignore until it’s unavoidable. The entry strips away the heroic image of bravery and replaces it with procrastination disguised as strength. People, he suggests, tolerate threats only until they’re forced to react. This cynical realism highlights how fear is managed more through avoidance than valor. Bierce doesn’t mock fear itself, but how it’s romanticized without true understanding.

In Debt, he captures economic dependency not as an unfortunate state, but as a system designed to imprison with invisible chains. Bierce equates owing money with moral failure and systemic exploitation, suggesting that modern economies thrive on people never being fully free. His commentary links finance to control, implying that wealth often grows not from creation, but from burdening others. The debtor becomes less a participant in the economy and more a captive of it. Bierce’s satire here critiques capitalism’s darker mechanics without directly naming them.

Debauchee carries a humorously damning tone. While society often paints indulgence as a flaw, Bierce frames it as the logical end of unguarded pleasure. The debauchee is not merely a sinner but a mirror reflecting the desires that others suppress. His language suggests that condemnation often masks envy, and that those most critical of vice may simply lack opportunity. Bierce turns moral scorn into a form of hypocrisy, poking at the social rituals that uphold virtue publicly while desiring excess privately.

Dawn, usually tied to renewal, is depicted as a favorite time of day for those eager to display discipline. Bierce mocks the early riser’s pride, implying that virtue gained by denying sleep is as shallow as it is tiring. His critique is aimed not at diligence, but the performance of it—the need to be seen as virtuous rather than actually being so. In a society obsessed with productivity, he suggests, routine often replaces reflection. By waking early, one may win social praise while losing personal peace.

Datary, a less common term, receives Bierce’s sharp ecclesiastical commentary. He defines it as a cleric’s administrative role tied more to power than spiritual calling. Through this, he critiques how institutions of faith often prioritize bureaucracy over belief. The tone is dry but cutting, suggesting that religion’s reach into human affairs has less to do with salvation and more with influence. This entry fits within his broader theme of exposing the mundane machinery behind exalted systems.

Dead receives one of the darkest and most poetic treatments. Bierce views death not as tragic, but inevitable, stripping it of mystique while maintaining its finality. He writes with the calm of someone resigned to fate, portraying the dead as the only truly silent observers of life’s chaos. It’s not death he mocks, but the ways we avoid its reality until it forces itself upon us. In doing so, he grants the dead a strange dignity—free from the illusions the living cling to.

Decalogue, or the Ten Commandments, is dissected not as a divine code, but as a socially convenient moral checklist. Bierce implies that commandments are followed when convenient and ignored when not, turning divine law into moral suggestion. His satire reframes these guidelines as a reflection of societal control rather than eternal truth. Morality, he suggests, is often interpreted through the lens of self-interest and circumstance. The sacred becomes conditional, and obedience becomes opportunistic.

With Diary, Bierce targets self-reflection, painting it as an exercise in self-deception rather than truth-telling. The diary writer, in his view, records not what happened, but what they wish had happened. Honesty is sacrificed for narrative control. He critiques how people reshape their pasts to match their present self-image, proving that memory is as flawed as it is personal. Bierce reminds us that introspection is often more about appearance than insight.

By the end of this chapter, Bierce has unraveled morality, discipline, and belief with surgical satire. His definitions don’t destroy meaning—they dissect it, layer by layer. Through irony, he exposes how human language often fails to capture the complexities of experience, instead simplifying, flattering, or distorting it. Each entry in this chapter forces readers to look again at the words they use and the values they reflect. Bierce’s mastery lies in his ability to make cynicism feel like clarity and wit feel like wisdom.

0 Comments