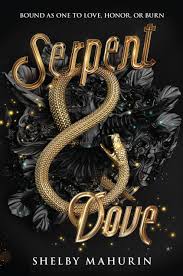

Serpent & Dove

Ye Olde Sisters: Lou

by Mahurin, ShelbyLou experiences a profound emotional shift upon hearing Reid’s declaration of love, which fills her with warmth and hope despite her fear as a witch. She believes his love will transcend her identity and protect her, but her moment of joy is interrupted by the Archbishop, who accuses her of deception. He dismisses her feelings as an act, insisting she cannot truly care for Reid. Tension rises as Lou edges toward a hidden knife, sensing danger, while the Archbishop quotes scripture, labeling her a serpent and vowing to end her influence over Reid.

Their confrontation is disrupted by a page boy announcing the start of a performance, forcing the Archbishop to delay his threats. Lou seizes the opportunity to urge him to leave, but he insists she accompany him, dragging her to the event against her will. The scene shifts to a bustling crowd gathered around a troupe of female performers, whose presence sparks murmurs of disapproval. The Archbishop condemns their profession as disgraceful, while Lou, amused, defends their talent. The youngest performer captivates the audience, setting the stage for a provocative play.

The performer introduces a darker twist on a familiar saint’s tale, hinting at a story involving an archbishop—a clear jab at Lou’s companion. As the crowd quiets in anticipation, a woman dressed in robes mimicking the Archbishop’s emerges, heightening the tension. The Archbishop stiffens, recognizing the mockery, while Lou watches with satisfaction. The performer’s mischievous grin and the troupe’s boldness underscore the chapter’s themes of defiance and subversion, challenging societal norms and religious authority.

The chapter culminates in a clash between tradition and rebellion, with Lou caught between the Archbishop’s hostility and the troupe’s audacious performance. Her internal conflict—balancing hope for Reid’s love with the reality of her precarious position—mirrors the external tension. The Sisters’ play promises to expose hypocrisy, leaving the Archbishop visibly unsettled and Lou poised between danger and empowerment. The scene sets the stage for further confrontation, blending personal stakes with broader societal critique.

FAQs

1. How does Lou’s emotional state change throughout the chapter, and what key moments trigger these shifts?

Answer:

Lou experiences significant emotional shifts in this chapter. Initially, she feels numb with fear until Reid’s declaration of love (“I love you, Lou”) fills her with warmth and hope, making her believe their relationship can overcome her secret identity as a witch. This euphoria is punctured when the Archbishop accuses her of deception, causing defensive tension. The confrontation escalates her fear, especially when he blocks access to her knife and quotes scripture to demonize her. Finally, the arrival of the all-female acting troupe provides a distraction and momentary relief, allowing Lou to regain some composure through sarcastic remarks about their talent.2. Analyze the Archbishop’s characterization in this chapter. What does his behavior reveal about his motives and worldview?

Answer:

The Archbishop is portrayed as dogmatic, manipulative, and threatening. His immediate dismissal of Lou’s genuine feelings for Reid (“we both know that isn’t possible”) reveals his deep prejudice against witches, whom he equates with biblical evil (referencing Revelation 12:9 about the “serpent of old”). His physical aggression—blocking the knife drawer and forcibly dragging Lou outside—shows his willingness to intimidate. His disgust at the all-female acting troupe (“A woman should never debase herself…”) underscores his misogyny. These traits suggest his primary motive is enforcing rigid orthodoxy, even through coercion.3. What symbolic significance does the Ye Olde Sisters troupe hold in the context of Lou’s conflict with the Archbishop?

Answer:

The troupe serves as a thematic counterpoint to the Archbishop’s repression. Their all-female composition challenges patriarchal norms, emphasized by the crowd’s whispered disapproval (“Women”). Their performance—a subversive retelling of a religious tale—mirrors Lou’s own defiance. The young actress’s confidence and the archbishop-costumed actor parody his authority, undermining his gravitas. For Lou, the troupe represents artistic and feminine resilience, offering both literal distraction (“You don’t want to keep them waiting”) and metaphorical hope that unconventional stories (like her love with Reid) can rewrite oppressive narratives.4. How does the chapter use physical objects and spaces to heighten tension? Provide specific examples.

Answer:

Physicality is central to the tension. The knife in the desk drawer becomes a focal point during Lou and the Archbishop’s standoff, symbolizing her vulnerability when he blocks access to it. The door amplifies claustrophobia when he shuts it with an “ominous snap,” trapping her. Later, the cathedral steps become a public battleground where Lou is forcibly paraded, contrasting with the private confrontation. Even the actors’ crimson and gold robes mirror the Archbishop’s attire, creating visual irony that unsettles him. These elements transform settings and objects into extensions of the power struggle.5. Evaluate Lou’s assertion that Reid’s love “changes everything.” Is her optimism justified based on the chapter’s events?

Answer:

Lou’s optimism is emotionally understandable but narratively precarious. While Reid’s love momentarily overrides her fear (“He would love me anyway”), the Archbishop’s intervention proves systemic barriers remain. His authority and bigotry threaten Lou despite Reid’s feelings, suggesting individual love cannot single-handedly dismantle institutionalized prejudice. The chapter ends with Lou still under the Archbishop’s control, implying unresolved conflict. Her hope is a catalyst for resilience, but the tension between personal bonds and societal forces remains unresolved—a deliberate setup for future trials.

Quotes

1. “I love you, Lou. […] He loved me. He loved me. This changed everything. If he loved me, it wouldn’t matter that I was a witch. He would love me anyway.”

This emotional revelation marks a pivotal moment for Lou, where she realizes the transformative power of unconditional love—a central theme in the chapter. It contrasts sharply with the Archbishop’s later accusations of deception.

2. “‘And the great dragon was thrown down, the serpent of old who is called the devil and Satan, who deceives the whole world.’ […] You are that serpent, Louise. A viper.”

The Archbishop’s biblical condemnation reveals the core conflict: Lou’s identity as a witch clashes with religious authority. This quote exemplifies the dehumanizing rhetoric used against her and foreshadows their ideological battle.

3. “The actors in this troupe were all women. […] Proud and erect, but also fluid. […] I don’t know what these idiots had expected. The troupe’s name was Ye Olde Sisters.”

This description of the all-female acting troupe challenges societal norms, mirroring Lou’s own defiance of expectations. The passage highlights themes of female autonomy and performance as subversion.

4. “‘Abominable.’ The Archbishop halted at the top of the steps, lip curling. ‘A woman should never debase herself with such a disreputable profession.’”

This quote crystallizes the Archbishop’s misogyny and sets up the cultural clash between tradition and progress that unfolds through the performance. His words contrast sharply with the celebratory description of the actresses.