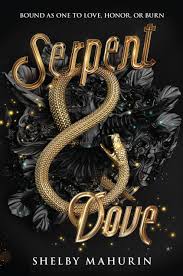

Serpent & Dove

The Ceremony: Reid

by Mahurin, ShelbyThe chapter opens with Reid, a disciplined and conflicted protagonist, struggling to maintain composure amid escalating chaos outside a theater. His heightened senses focus on the footsteps of a mysterious woman—light yet erratic—as the crowd demands justice. Despite the Archbishop’s attempts to calm the situation, Reid’s internal turmoil is palpable, his body reacting with a mix of heat and cold. The woman’s presence, marked by her broken fingers and hidden scars, unsettles him further, especially as memories of Célie, a pure and unblemished figure from his past, flood his mind.

Reid’s internal conflict deepens as the Archbishop presents the woman to the crowd, framing her as a wayward heathen in need of salvation. The woman clings to Reid’s arm, her fear evident, but he resists acknowledging her fully, torn between duty and disdain. The Archbishop’s sermon condemns her rebellious nature, urging the crowd to see her as a lesson in obedience. Meanwhile, Reid grapples with guilt over Célie’s rejection, her words haunting him: *“Give [your heart] to your brotherhood.”* The crowd’s mixed reactions—some sympathetic, others vicious—highlight the tension between societal expectations and individual morality.

The scene takes a darkly comedic turn when the Archbishop is suddenly afflicted by an inexplicable bout of flatulence, disrupting his solemn address. Reid suspects magic at play, but the woman’s laughter and the absence of magical scent on her leave him baffled. Her irreverent amusement contrasts sharply with Reid’s rigid demeanor, underscoring their ideological clash. The Archbishop’s humiliation forces him to retreat, leaving Reid and the woman to continue their journey to the Doleur for her baptism—a task Reid resents but cannot refuse.

As they walk, the woman’s defiance and wit continue to irk Reid, her mocking commentary on the Archbishop’s misfortune revealing her rebellious spirit. Despite his disgust, Reid is forced to play the role of her husband, a charade that grates against his sense of duty. The chapter closes with their uneasy dynamic unresolved, setting the stage for further conflict. The woman’s laughter lingers as a symbol of resistance, while Reid’s internal struggle between faith, duty, and suppressed emotions remains central to the narrative.

FAQs

1. How does Reid’s internal conflict manifest during the ceremony scene, and what does this reveal about his character?

Answer:

Reid’s internal conflict is vividly portrayed through physiological and psychological reactions—his blood roaring in his ears, skin feeling “hot and cold,” and despair nearly knocking him to his knees. These physical sensations mirror his emotional turmoil, particularly his guilt over Célie and his forced proximity to the “heathen” woman. His refusal to look at the woman’s face, despite noticing her injuries, reveals his self-loathing and cognitive dissonance: he is repulsed by her yet complicit in the Archbishop’s performative “salvation” of her. This underscores Reid’s internal struggle between duty (to his brotherhood) and personal morality, painting him as a conflicted figure trapped by external expectations.

2. Analyze the significance of the Archbishop’s public speech and the crowd’s reactions. How does this scene critique societal power structures?

Answer:

The Archbishop’s speech weaponizes religious rhetoric to justify misogyny and control, framing the woman’s abuse as “discipline” and her resistance as “sinful.” The crowd’s murmurs of agreement (“Womenfolk are as bad as witches”) highlight how institutional power (here, the Church) legitimizes oppression through dogma. Meanwhile, the pale-haired woman’s silent fury and the heathen’s magical retaliation (the Archbishop’s humiliating flatulence) serve as subversive challenges to this authority. The scene critiques how power structures manipulate narratives to maintain dominance, while also showing how marginalized individuals resist—whether through open defiance (the pale-haired woman) or covert magic (the heathen).

3. What role does sensory detail play in conveying the dynamic between Reid and the heathen woman?

Answer:

Sensory details—particularly sound and touch—intimately frame their fraught connection. Reid hyper-focuses on her “light, erratic” footsteps, which cut through his internal chaos, suggesting an unconscious pull toward her. Her “small, warm hand” on his arm, with its callouses and broken fingers, humanizes her despite his attempts to dehumanize her as a “heathen.” The contrast between her cinnamon scent (natural) and the faint magic he detects further complicates his perception of her as both ordinary and dangerous. These details create a tension between Reid’s imposed disdain and his involuntary attentiveness, foreshadowing potential shifts in their relationship.

4. How does the heathen woman’s use of magic serve as both a literal and symbolic act of rebellion?

Answer:

Her magic—manifested in the Archbishop’s humiliating public flatulence—is a literal act of defiance, undermining his authority in a way that elicits laughter rather than fear. Symbolically, it represents the subversion of patriarchal and religious control: where the Archbishop uses words to shame, she uses magic to expose his bodily vulnerability. Her whispered remark (“worth marrying you… I’ll cherish it forever”) reframes the ceremony as a victory, not a submission. This mirrors broader themes of resistance, showing how marginalized individuals reclaim agency through unconventional means.

5. Compare Reid’s perception of Célie and the heathen woman. What does this contrast reveal about his biases?

Answer:

Reid idolizes Célie as “unblemished and pure,” a memory tied to guilt and unattainable ideals, while he reduces the heathen to her scars and “wild” appearance. His fixation on Célie’s purity reflects a binary worldview (virgin/whore, sacred/profane), which the heathen’s complexity disrupts. Her laughter, resilience, and magic defy his stereotypes, yet he clings to loathing her to avoid confronting his complicity in her suffering. This contrast exposes Reid’s internalized misogyny and the hypocrisy of his brotherhood’s moral framework, which glorifies some women while condemning others.

Quotes

1. “Light. Lighter than mine. But more erratic. Less measured.”

This quote captures Reid’s hyper-awareness of the woman’s presence through her footsteps, revealing his conflicted attention toward her despite his attempts to ignore her. It shows the tension between his disciplined nature and her unpredictable energy.

2. “You cannot give me your heart, Reid. I cannot have it on my conscience… Those monsters who murdered Pip are still out there. They must be punished.”

This memory of Célie’s rejection highlights Reid’s inner turmoil and sense of duty, explaining his emotional state during the ceremony. It frames his despair and the sacrificial nature of his current situation.

3. “Learn from her wickedness! Wives, obey your husbands. Repent your sinful natures. Only then can you be truly united with God!”

The Archbishop’s harsh sermon represents the oppressive religious ideology of their society. This quote is significant as it shows the institutional justification for controlling women, which the chapter challenges through the heathen’s defiance.

4. “This right here—this exact moment—it just might be worth marrying you, Chass. I’m going to cherish it forever.”

The heathen’s laughter at the Archbishop’s humiliation demonstrates her subversive humor and resistance to authority. This moment marks a turning point where Reid begins to recognize her rebellious spirit firsthand.