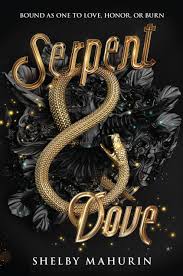

Serpent & Dove

Lord, Have Mercy: Lou

by Mahurin, ShelbyThe chapter opens with Lou and her husband attending evening Mass at Saint-Cécile, where the stifling atmosphere and tedious rituals test her patience. The Archbishop reminisces about his youthful archery skills, prompting a polite but strained exchange. Lou, bored and drowsy in her heavy wool gown, muses that staying awake would be a miracle. Her irreverent attitude contrasts sharply with the solemnity of the setting, highlighting her discomfort with religious formalities.

Earlier in the day, Lou had reluctantly agreed to memorize scripture after a confrontation in the library. Her husband, still irritated, quotes proverbs while Lou responds with sarcastic retorts, turning the lesson into a battle of wits. Their banter reveals her rebellious nature and his frustration, though the invitation to Mass offers a temporary truce. The Archbishop’s cryptic warning to her husband about keeping “a closer eye” sparks Lou’s curiosity, but he deflects her questions, further straining their dynamic.

Inside the sanctuary, the opulence of the wealthy congregants contrasts with the humble attire of the poor, emphasizing the social divide. Lou’s discomfort grows as she realizes they must stand for the entire service. Her husband’s insistence on joining the Chasseurs—including Jean Luc—forces her into an unfamiliar role. When the congregation begins chanting, Lou improvises irreverent lyrics, amusing Jean Luc but irritating her husband, underscoring her outsider status.

The chapter culminates as the Archbishop begins the Mass, with Lou observing the rituals with detached amusement. Her husband’s stern reactions and Jean Luc’s suppressed laughter hint at the tension between Lou’s defiance and the rigid expectations of the Church. The scene sets the stage for further conflict, as Lou’s presence in this devout environment remains a source of friction and unspoken secrets.

FAQs

1. How does Lou’s attitude toward religious practices contrast with her husband’s and the Chasseurs’ devotion?

Answer:

Lou displays irreverence and boredom toward religious rituals, as seen through her sarcastic commentary, made-up lyrics during Mass, and frequent yawns. In contrast, her husband and the Chasseurs participate earnestly—standing humbly, reciting scriptures, and engaging in solemn rituals. While Lou views scripture memorization as “the most diabolical of all punishments,” her husband insists on her participation, highlighting their ideological clash. The chapter underscores Lou’s outsider status as a non-believer (and likely a witch) in this devout environment, particularly when she lies about attending Mass before and struggles to blend in.

2. What does the Archbishop’s remark about “a closer eye” suggest about the underlying tensions in the story?

Answer:

The Archbishop’s instruction to maintain “a closer eye” implies growing suspicion toward Lou or her husband’s oversight. Earlier, initiates were blamed for the “library fiasco,” but this vague warning hints at deeper scrutiny—possibly of Lou’s behavior or her husband’s loyalty. The husband’s flushed reaction and deflection when questioned suggest he may be caught between his duty and protecting Lou. This foreshadows future conflict, as the Church’s surveillance could expose Lou’s secrets or test their marriage.

3. Analyze the significance of the socioeconomic divide depicted during Mass. How might this reflect broader themes in the novel?

Answer:

The stark contrast between the wealthy seated congregation (adorned in jewels and finery) and the poor standing at the back (dirty and solemn) mirrors societal inequality. The Chasseurs, though enforcers of the Church, stand with the poor—a performative “act of humility” that may critique institutional hypocrisy. Lou’s discomfort amid the crowd also reflects her precarious position: she’s neither part of the elite nor the devout working class. This divide may hint at broader themes of power, class struggle, and the Church’s role in perpetuating systemic disparities.

4. How does the chapter use humor to characterize Lou and her dynamic with her husband?

Answer:

Lou’s wit and sarcasm humanize her and defuse tension. For example, she twists scripture into jokes (“Rain and men are both pains in the ass”) and sings inappropriate lyrics during Mass, annoying her husband but amusing Jean Luc. Their banter—like her teasing about “ointment and a hand”—showcases their combative yet playful relationship. Humor also underscores Lou’s defiance; even in a restrictive setting, she refuses to conform, using laughter as both armor and rebellion against her husband’s rigid expectations.

5. What might the Archbishop’s archery anecdote reveal about the Church’s values and Lou’s husband’s past?

Answer:

The Archbishop’s story of hitting a bull’s-eye as a child frames skill as divine favor, reinforcing the Church’s belief in predestined superiority. His praise for Lou’s husband’s “natural talent” suggests the latter was a prodigy, possibly groomed for leadership. This contrasts with Lou’s disinterest, positioning her as an outsider to this culture of discipline and destiny. The anecdote also hints at the husband’s internal conflict: his praised past versus his present entanglement with Lou, whose irreverence challenges everything he was trained to uphold.

Quotes

1. “‘A continual dropping in a very rainy day and a contentious woman are alike,’ he’d recited, eyeing me irritably and waiting for me to repeat the verse. Still peeved from our earlier argument. / ‘Rain and men are both pains in the ass.’”

This exchange highlights the protagonist Lou’s irreverent wit and her combative dynamic with her husband. It showcases her resistance to religious dogma and her subversion of traditional gender roles through humor.

2. “‘Iron sharpeneth iron; so a man sharpeneth the countenance of his friend.’ / ‘Iron sharpeneth iron, so you’re being an ass because I, too, am a piece of metal.’”

Another example of Lou’s clever wordplay that transforms biblical proverbs into modern sarcasm. This demonstrates her intellectual agility and how she uses humor as both defense and rebellion against patriarchal structures.

3. “Lit by hundreds of candles, the sanctuary of Saint-Cécile looked like something out of a dream—or a nightmare.”

This vivid description captures the dual nature of Lou’s experience with religion - simultaneously beautiful and oppressive. The imagery reflects her conflicted position as both outsider and participant in this world.

4. “‘Chasseurs stand as an act of humility.’ / ‘But I’m not a Chasseur—’ / ‘And praise God for that.’”

This tense exchange reveals the ongoing power struggle between Lou and her husband, while also humorously acknowledging her unsuitability for religious conformity. It underscores the central tension of her character - being forced into a world she doesn’t belong to.

5. “Bewildered—and unable to comprehend a word of their dreary ballad—I made up my own lyrics. / They may or may not have involved a barmaid named Liddy.”

This passage perfectly encapsulates Lou’s irreverent spirit and refusal to participate sincerely in religious rituals. Her internal rebellion through improvised lyrics demonstrates her creative resistance to enforced piety.