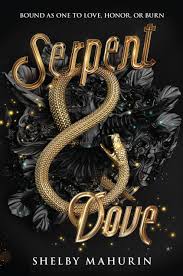

Serpent & Dove

A Man’s Name: Reid

by Mahurin, ShelbyThe chapter opens with Captain Reid Diggory arriving at Tremblay’s townhouse, which is saturated with the lingering scent of magic. He observes Madame Labelle, a notorious courtesan, assisting Tremblay with unconscious guards, while Tremblay’s wife watches with visible disdain. The tension escalates as Célie Tremblay, clad in mourning attire, greets Reid with strained politeness. Their interaction is fraught with unspoken emotions, hinting at a shared history of loss. Reid’s professional demeanor clashes with his personal concern for Célie, even as he asserts his duty to investigate potential witchcraft.

Madame Tremblay insists their home is free of witchcraft, blaming the nearby park for the strange odors, while Reid and his fellow Chasseur, Jean Luc, debate the necessity of their presence. Madame Labelle’s arrival further complicates the scene, as her cryptic remarks and exchanged glances with Tremblay suggest hidden agendas. The confrontation between Madame Tremblay and Labelle reveals underlying tensions, with Célie caught in the middle. Reid’s suspicion grows as he notices the Tremblays’ unease and the gathering crowd of onlookers.

Reid’s attention is drawn to an upstairs window, where he spots two figures—one of whom he recognizes from a previous encounter. The woman’s disguised appearance and panicked reaction fuel his determination to uncover the truth. Despite Jean Luc’s eagerness to label her a witch, Reid hesitates, recalling her lack of magical aura during their earlier meeting. His internal conflict reflects the broader theme of justice versus prejudice, as he grapples with the Archbishop’s teachings and his own observations.

The chapter culminates in Reid’s resolve to pursue the suspects, driven by a mix of duty and personal conviction. His fleeting doubt about the woman’s guilt contrasts with Jean Luc’s unwavering zeal, setting the stage for a moral and tactical clash. The scene underscores the pervasive fear of witchcraft and the complexities of discerning truth in a world where appearances deceive. Reid’s final thoughts echo a biblical call for justice, hinting at the deeper ideological struggles that will shape his actions moving forward.

FAQs

1. What evidence suggests witchcraft may be involved in the scene at Tremblay’s townhouse?

Answer:

The text provides several indicators of potential witchcraft: the townhouse “reeked of magic” that coated the lawn and clung to the unconscious guards (p. 57). Reid notes the magical residue is unmistakable, though Madame Tremblay attributes it to a nearby park. Additionally, the Chasseurs received an anonymous tip about a witch’s presence that coincided with the robbery (p. 59), creating suspicious circumstances. The guards’ complete memory loss—a common trope associated with magical interference—further supports this possibility (p. 59). These details collectively suggest supernatural involvement beyond a simple theft.2. Analyze the complex social dynamics between Madame Tremblay, Madame Labelle, and Tremblay. What does this reveal about their relationships?

Answer:

The interactions reveal a tense love triangle and class conflict. Madame Tremblay’s hostility toward Madame Labelle—a “notorious courtesan” (p. 57)—is evident through her sarcastic remarks about Labelle’s presence in their neighborhood (p. 59-60). Labelle’s coy response about having “business” with Tremblay (p. 60) implies an affair, which Tremblay’s hasty intervention supports. Meanwhile, Célie’s visible distress (p. 58) suggests awareness of this tension. The scene highlights societal hypocrisy: Labelle is scorned yet tolerated due to her connections, while the Tremblays maintain a façade of respectability despite underlying dysfunction.3. How does Reid’s internal conflict about the female thief reflect his character development?

Answer:

Reid demonstrates cognitive dissonance between his duty and personal observations. Despite his initial zeal for witch-hunting (“it will burn,” p. 58), he hesitates to label the woman a witch, recalling her vanilla-cinnamon scent and non-threatening appearance during their earlier encounter (p. 61). This contradicts his training that “every woman is a potential threat” (p. 61), showing emerging doubt. His physical reaction (blushing, p. 61) suggests attraction complicating his judgment. This moment foreshadows potential moral growth as Reid begins to question rigid dogma in favor of empirical evidence and human connection.4. Compare the narrative significance of the two settings described: the chaotic townhouse scene and the earlier parade encounter.

Answer:

The parade (referenced on p. 61) represents Reid’s initial, impersonal view of society—a public space where he briefly connected with the thief amidst crowds. In contrast, the townhouse is a private sphere exposing hidden tensions: marital strife, class divides, and magical threats. The parade allowed accidental intimacy (their collision), while the townhouse forces deliberate confrontation. Both settings reveal Reid’s dual roles—as a Chasseur enforcing order and as a man capable of personal connection. The contrast highlights how different environments shape his perceptions of justice and humanity.5. Evaluate how the chapter uses religious imagery to frame Reid’s pursuit of justice.

Answer:

Reid’s quote from Amos 5:24 (“Let justice roll on like a river,” p. 60) sanctifies his mission, portraying witch-hunting as divine mandate. However, this contrasts with the scene’s moral ambiguity: the “righteous” Tremblays’ marital discord, Labelle’s implied prostitution, and Reid’s own conflicted feelings. The biblical language ironically underscores human fallibility—Reid’s certainty (“Justice,” p. 60) is undercut by his later doubts. The Archbishop’s teachings (p. 61) are presented as doctrine, yet Reid’s instincts challenge them, suggesting a tension between blind faith and experiential truth that critiques dogmatic absolutism.

Quotes

1. “Tremblay’s townhouse reeked of magic. It coated the lawn, clung to the prone guards Tremblay attempted to revive.”

This opening line sets the ominous tone of the chapter, immediately establishing the presence of witchcraft as a central theme. The visceral description of magic’s lingering effects creates tension and foreshadows the conflict to come.

2. “I longed to close the distance between us and wipe them away. To wipe this whole nightmarish scene—so like the night we’d found Filippa—away.”

This quote reveals Reid’s inner conflict and emotional vulnerability, contrasting with his professional demeanor. It hints at past trauma (Filippa’s death) that continues to haunt him, adding depth to his character.

3. “I assure you, sir, you and your esteemed order are not necessary here. My husband and I are God-fearing citizens, and we do not abide witchcraft—”

Madame Tremblay’s defensive protest highlights the social stigma surrounding witchcraft and the tension between public reputation and private reality. Her insistence on respectability contrasts sharply with the magical evidence surrounding her home.

4. “Let justice roll on like a river, and righteousness like a never-failing stream.”

This biblical reference encapsulates Reid’s fanatical devotion to his witch-hunting cause. The quote represents a key turning point where he shifts from investigator to zealot, convinced he’s serving divine justice.

5. “The Archbishop had been clear in our training—every woman was a potential threat. Even so… ‘I don’t think she’s a witch.’”

This internal struggle showcases the conflict between Reid’s indoctrination and his personal observations. The hesitation marks a significant moment where his beliefs are challenged by his instincts, foreshadowing potential character development.