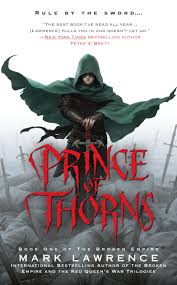

Prince of Thorns

Chapter 46

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with the protagonist, disguised as Sir Alain, entering a brutal Grand Mêlée tournament. The announcer introduces the competing knights, each armed with weapons designed to crush armor and bone. The protagonist, wielding only a sword, observes the grim reality of such battles: defeating armored opponents often requires bludgeoning them into submission before delivering a fatal blow. The scene is set with Count Renar and the enigmatic Corion watching from the stands, adding an air of tension and foreboding to the violent spectacle about to unfold.

As the battle commences, the protagonist quickly dispatches two knights with lethal precision, defying the unspoken rules of the tourney, which typically discourage outright killing. His ruthless efficiency draws attention, particularly from Sir William of Brond, whom he also kills after a brief exchange. The protagonist’s disregard for convention—such as targeting a knight’s horse—further marks him as an outsider. The chaos of the Mêlée is vividly depicted, with blood, screams, and the clatter of weapons filling the field, while the protagonist embraces the brutality, seeing it as a means to eliminate potential threats.

The aftermath of the carnage leaves few knights standing, including Sir James of Hay, a formidable opponent who advances on the protagonist with grim determination. The protagonist, now drenched in blood, reflects on his actions and the possibility that Corion, a shadowy figure from his past, has manipulated events to bring him to this moment. The tension escalates as Sir James, silent and relentless, engages him in a one-sided duel, overpowering him with sheer strength and nearly killing him with his axe.

In the final moments, the protagonist faces imminent death, his earlier bravado replaced by raw fear. The chapter ends on a cliffhanger, leaving his fate uncertain as Sir James prepares to deliver what seems like a final blow. The protagonist’s internal monologue reveals a stark realization of his mortality, contrasting sharply with his earlier ruthless confidence. The scene underscores the themes of manipulation, violence, and the thin line between control and chaos in a world where power and survival are inextricably linked.

FAQs

1. What are the key differences between the protagonist’s approach to the Grand Mêlée and the traditional expectations of a tournament?

Answer:

The protagonist subverts traditional tournament norms by employing lethal tactics rather than the expected non-fatal combat. Typically, knights aim to unhorse or stun opponents, with deaths being rare and accidental (often occurring later from injuries). However, the protagonist uses his sword to kill outright, targets horses (a taboo due to their value), and shows no concern for consequences like retaliation. This reflects his pragmatic, ruthless mindset—prioritizing survival and reducing future threats over chivalric ideals. The text notes this divergence when mentioning “it’s not the done thing” to slaughter opponents, highlighting his outsider status.

2. How does the author use sensory details to immerse the reader in the brutality of the combat?

Answer:

The chapter employs vivid sensory imagery to convey the gore and chaos of battle. Visual details like “bright with arterial blood” and “the pitter-pat of blood dripping from my plate-mail” emphasize the protagonist’s transformation into a “Red Knight.” Olfactory and tactile elements—”the stink of battle… blood and shit, the taste of it on my lips, salt with sweat”—ground the violence in physicality. Auditory cues, such as the horse’s “screaming and thrashing” or the “distant clash of weapons,” further heighten realism. These details collectively create a visceral, unsettling atmosphere that contrasts with the pageantry typically associated with tournaments.

3. Analyze the significance of the protagonist’s encounter with Corion. How does it reflect his psychological state?

Answer:

The protagonist’s dread upon noticing Corion—who “draws the eye as the lodestone pulls iron”—reveals his paranoia and sense of manipulation. Corion symbolizes unseen control, having previously “poisoned [his] every move.” The protagonist wonders if Corion orchestrated his presence at the tournament, reflecting his existential uncertainty: “Had he drawn me here… tugging on his puppet lines?” This moment underscores his internal conflict between agency and fatalism, as he questions whether his actions are truly his own. The tension peaks when he considers death by combat preferable to facing Corion, highlighting his psychological torment.

4. What does the protagonist’s interaction with Sir James of Hay reveal about their respective combat philosophies?

Answer:

Sir James embodies traditional knightly values: he offers a single chance to yield (“One chance”) and fights with disciplined strength, relying on his axe’s brute force. The protagonist, in contrast, combines dark humor (“You’re a scary one”) with ruthless pragmatism, exploiting distractions (e.g., talking mid-fight) and prioritizing survival over honor. Their clash illustrates the tension between chivalric codes and the protagonist’s nihilistic adaptability. His musing that “we don’t even have choices” further contrasts with Sir James’s straightforward challenge, emphasizing their ideological divide.

5. How does the chapter use irony to critique the romanticized portrayal of medieval tournaments?

Answer:

The chapter deconstructs tournament tropes through ironic contrasts. While events like the Grand Mêléé are often glorified, the protagonist highlights their grim reality: armor is “opened” like cans, deaths are common, and injuries are severe. The applause for entrants is “half-hearted,” and the “lucky thirteen” knights quickly dwindle to a blood-soaked few. The protagonist’s matter-of-fact tone—describing coup de grâce techniques or the cost of killing horses—underscores the disconnect between pageantry and violence. This irony critiques idealized medievalism, exposing tournaments as brutal, pragmatic affairs rather than noble spectacles.

Quotes

1. “When you fight a man in full plate, it’s normally a matter of bludgeoning him to a point at which he’s so crippled you can deliver the coup de grâce with a knife slipped between gorget and breastplate, or through an eye-slot.”

This quote starkly illustrates the brutal reality of medieval combat, stripping away any romanticism. It reveals the protagonist’s pragmatic and merciless approach to battle, setting the tone for the violent tourney scene.

2. “It’s not the done thing to set to bloody slaughter at tourney… When a knight gets too thirsty for blood, he often finds himself meeting his opponent’s friends and family in unpleasant circumstances shortly after.”

This passage highlights the unspoken rules of chivalric combat, which the protagonist deliberately violates. It underscores the tension between societal expectations and his own ruthless agenda.

3. “If the sight of a heavy warhorse thundering toward you doesn’t make at least part of you want to up and run, then you’re a corpse.”

This vivid description captures the raw terror of medieval warfare while revealing the protagonist’s survival instincts. The blunt metaphor emphasizes his world-weary perspective on combat.

4. “I had the stink of battle in my nose now, blood and shit, the taste of it on my lips, salt with sweat.”

This visceral sensory description marks the protagonist’s full immersion in violence. It represents a turning point where the tourney shifts from formal competition to brutal survival.

5. “I’m not sure we even have choices, James, let alone chances. You should read—”

This truncated philosophical remark, delivered mid-combat, reflects the protagonist’s fatalistic worldview and hints at deeper themes of predestination versus free will that permeate the narrative.