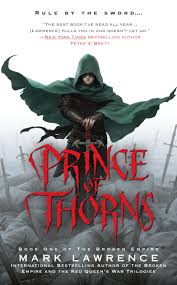

Prince of Thorns

Chapter 1

by Mark, Lawrence,The chapter opens with a grim scene in the town of Mabberton, where the aftermath of a brutal battle is described in vivid detail. The narrator, Jorg, observes ravens gathering over the corpses as his companion, Rike, loots the dead. The town square is drenched in blood, with corpses strewn about in grotesque poses. Jorg reflects on the irony of war, calling it a “thing of beauty” despite the carnage, and notes how the farmers’ defiance led to their slaughter. His cold detachment and dark humor underscore his ruthless nature.

Jorg’s interactions with his fellow warriors reveal the dynamics of their group. Rike, greedy and violent, complains about the meager spoils, while Jorg hints at other forms of “gold” to be found. Makin, the peacemaker, diffuses tension with jokes and suggests seeking out farmers’ daughters as part of their plunder. The camaraderie among the men is laced with brutality, as they casually discuss their next targets. Jorg’s authority is evident as he silences Rike with a warning look, asserting his control over the group.

The narrative shifts to Jorg’s confrontation with Bovid Tor, the dying leader of the farmers. Bovid, mortally wounded, addresses Jorg as “boy,” provoking his anger. Jorg taunts him about the fate of his potential daughters, revealing his cruelty. Bovid’s disbelief at Jorg’s youth—mistaking him for fifteen—fuels Jorg’s indignation, as he boasts of his ambitions to become king by that age. The exchange highlights Jorg’s pride and his obsession with power and recognition, even in the face of death.

The chapter closes with Jorg ordering Bovid’s decapitation, leaving his body for the ravens. His final thoughts dismiss Bovid’s underestimation of him, reinforcing his determination to achieve greatness. The last line, referencing Brother Gemt’s abrasive nature, adds a darkly humorous note, encapsulating the chapter’s tone of violence and defiance. Jorg’s nihilistic worldview and relentless drive for dominance are central to the chapter’s themes.

FAQs

1. Comprehension: What is the significance of the ravens in the opening scene, and how do they set the tone for the chapter?

Answer:

The ravens serve as a grim harbinger of death, arriving even before the wounded have died, which immediately establishes a dark and foreboding tone. Their presence symbolizes the inevitability of death and the characters’ familiarity with violence. The narrator’s casual nod to the birds suggests his desensitization to brutality, reinforcing the chapter’s themes of war and moral ambiguity. The ravens’ “wise-eyed and watching” demeanor also implies a supernatural or omniscient perspective on the carnage, adding a layer of ominous observation to the scene.2. Analytical: How does the narrator’s perspective on war contrast with the likely views of his victims, and what does this reveal about his character?

Answer:

The narrator describes war as “a thing of beauty,” a stark contrast to the suffering of the dying farmers, like Bovid Tor, who would undoubtedly view it as horrific. This juxtaposition reveals the narrator’s nihilistic and jaded worldview, shaped by his life of violence. His detachment—referring to corpses as “comical” or “peaceful”—highlights his emotional numbness and hints at a traumatic past that has warped his morality. His pride in the “magic” of the scene and dismissal of Rike’s greed further illustrate his twisted aesthetic appreciation for destruction.3. Critical Thinking: The narrator claims he gave the farmers a chance to avoid slaughter. Does this assertion hold up under scrutiny, and what might it suggest about his self-justification?

Answer:

The narrator’s claim is likely a hollow justification for his actions. While he states he warned Bovid’s group “we do this for a living,” his tone is mocking, and the farmers’ tools (scythes, axes) suggest they were defending themselves, not seeking battle. His admission that he “always” offers a chance rings false, given the gleeful description of carnage. This contradiction exposes his need to frame himself as merciful or honorable, a common trait in morally ambiguous characters who rationalize violence to preserve their self-image.4. Application: How might the dynamic between the narrator, Rike, and Makin reflect broader themes of power and camaraderie in violent groups?

Answer:

Their interactions reveal a hierarchy maintained through intimidation and dark humor. The narrator asserts dominance over Rike with a “warning look,” while Makin mediates with jokes, illustrating how groups like theirs balance aggression and cohesion. Rike’s greed and Makin’s crude humor serve as coping mechanisms for their brutality, mirroring real-world violent groups where shared norms (e.g., dehumanizing victims) strengthen bonds. The narrator’s control—redirecting Rike’s anger toward “farmer’s daughters”—shows how leaders manipulate followers by appealing to base desires.5. Reflection: Why does the narrator fixate on Bovid’s question about his age, and how does this moment complicate his character?

Answer:

Bovid’s disbelief that the narrator is “fifteen summers” old triggers a defensive outburst, revealing insecurity beneath his ruthless facade. His anger at being called “boy” suggests a need to prove his maturity and power, hinting at unresolved trauma (e.g., forced early exposure to violence). The declaration “I’d be King by fifteen” exposes his ambition and perhaps a desire to transcend his brutal role. This moment humanizes him, suggesting his brutality is partly performance, and foreshadows deeper motivations driving his actions.

Quotes

1. “War, my friends, is a thing of beauty. Those as says otherwise are losing.”

This quote captures the protagonist Jorg’s twisted philosophy on violence and power. It establishes the chapter’s dark tone and his nihilistic worldview, where war is both an art form and a measure of success.

2. “I gave them that chance, I always do. But no. They wanted blood and slaughter. And they got it.”

This reveals Jorg’s self-justification for violence, portraying himself as merciful while simultaneously glorifying the carnage. It’s key to understanding his manipulative nature and the chapter’s exploration of moral ambiguity.

3. “Fifteen! I’d hardly be fifteen and rousting villages. By the time fifteen came around, I’d be King!”

This climactic quote shows Jorg’s ruthless ambition and youthful arrogance. It serves as both a character revelation and a thematic statement about power, age, and destiny in the narrative.

4. “Some people are born to rub you the wrong way. Brother Gemt was born to rub the world the wrong way.”

This closing observation about another character reflects back on Jorg himself, subtly suggesting his own role as an agent of chaos. It encapsulates the chapter’s exploration of inherent nature versus choice.