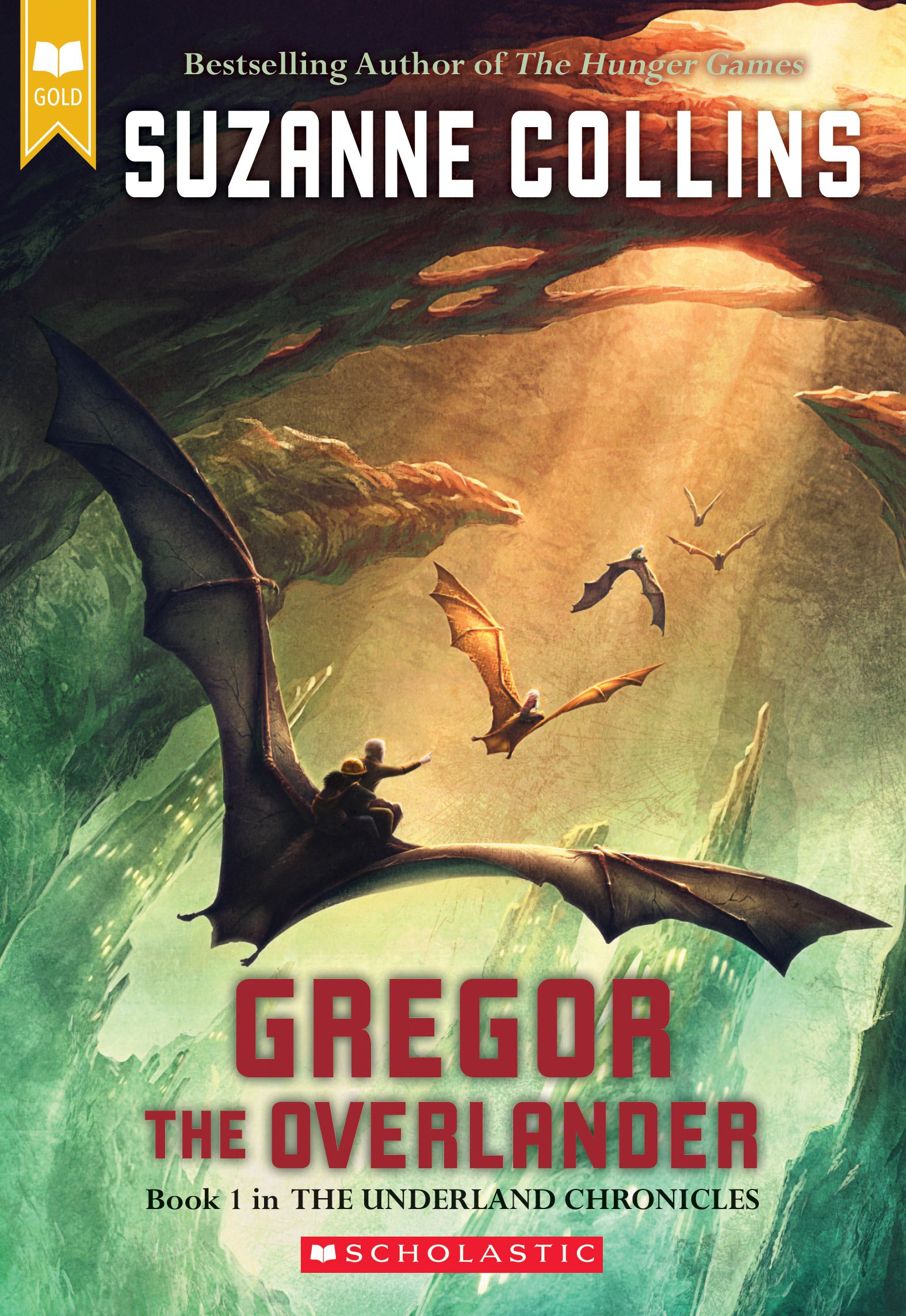

Gregor the Overlander

Chapter 1

by Suzanne, Collins,Gregor, an eleven-year-old boy, is stuck at home during a sweltering summer, frustrated by the heat and boredom. He resents missing summer camp but suppresses his anger, knowing he must care for his two-year-old sister, Boots, while his mother works. His grandmother, who often confuses him with someone named Simon, adds to the household’s challenges. The family’s financial struggles are evident—their only air-conditioned room is overcrowded, and Gregor’s clothes are repurposed from winter wear. The courtyard outside, usually lively with children, is deserted, emphasizing Gregor’s isolation.

Gregor reflects on his family’s changed dynamics since his father’s unexplained disappearance. As the oldest, he has taken on responsibilities like babysitting Boots and managing household tasks. His mother’s guilt over his missed camp opportunity is palpable, but Gregor downplays his disappointment to spare her feelings. His younger sister, Lizzie, avoids sharing his burden, leaving Gregor to shoulder the monotony of summer alone. The chapter highlights his quiet resignation to his role, though his frustration simmers beneath the surface.

The grandmother’s dementia provides moments of bittersweet humor and sadness. She often reminisces about her rural past, mistaking Gregor for a farmhand named Simon. Gregor envies her mental escape to a happier time, contrasting with his own stifling reality. Boots, meanwhile, is a source of fleeting joy, her playful demands offering brief distractions. When Mrs. Cormaci, a neighbor, arrives to babysit, Gregor is relieved to escape the apartment, even if only to do laundry.

The chapter closes with Gregor’s mundane laundry-room struggles, symbolizing his constrained life. Boots’s antics and the trivial dilemma of sorting laundry underscore his mundane responsibilities. The tennis ball she chases becomes a metaphor for Gregor’s own trapped existence—repetitive and unchanging. Despite his resilience, the chapter paints a poignant picture of a boy prematurely burdened by adulthood, yearning for freedom but bound by duty.

FAQs

1. How does the author establish Gregor’s sense of frustration and confinement in the opening scene?

Answer:

The author vividly portrays Gregor’s frustration through physical and emotional details. Pressing his forehead against the screen leaves visible marks, symbolizing his prolonged entrapment. His suppressed “primal caveman scream” reflects deep, unexpressed anger about his circumstances. The oppressive summer heat and boredom compound his sense of being stuck, emphasized by his observation of the deserted courtyard where other children have escaped to camp. The recurring imagery of heat (“lukewarm” room, melting ice cube) mirrors his stifled emotions, while his resigned interaction with his grandmother and Boots underscores his trapped role as a caretaker.2. Analyze how Gregor’s family dynamics shape his responsibilities and outlook.

Answer:

Gregor’s family situation forces him into premature adulthood. His father’s disappearance has left him as the “oldest” male figure, requiring him to care for Boots and accommodate his grandmother’s dementia. His mother’s work schedule and financial constraints (evident in their rundown apartment and hand-me-down clothes) further burden him. While he resents missing camp, he suppresses his disappointment to protect Lizzie and avoid adding to his mother’s guilt. The chapter highlights this tension through small acts—like Gregor lying about being “fine” with summer plans or prioritizing Boots’ needs over his own desires—showcasing his complex mix of resentment and reluctant responsibility.3. What symbolic significance do the rats and the laundry hold in Gregor’s world?

Answer:

The rats scurrying near the trash represent Gregor’s inescapable struggles—they’re persistent, unsettling, and emblematic of his lower-class environment. Similarly, the laundry scene underscores his mundane burdens: sorting mismatched clothes mirrors his patchwork family life (e.g., grandma’s quilt made from old dresses). The grayish, faded garments reflect their financial strain, while Boots’ black-and-white-striped shorts symbolize Gregor’s uncertain choices as a stand-in parent. Both details reinforce themes of decay and improvisation, mirroring how Gregor must “make do” in a world where better options (like camp) are out of reach.4. How does the author use contrasting settings to emphasize Gregor’s emotional state?

Answer:

Sharp contrasts heighten Gregor’s isolation. The air-conditioned bedroom (a sanctuary for Boots and Lizzie) opposes the sweltering living space where Gregor sleeps, physically mirroring his role as the family’s “outsider.” The vibrant courtyard, usually full of playing children, lies deserted—a visual metaphor for his exclusion from normal childhood experiences. Meanwhile, his grandmother’s mental retreat to a Virginia farm contrasts with Gregor’s grim reality in New York. These juxtapositions underscore his emotional displacement: he’s neither fully part of the child’s world nor the adult’s, stuck between responsibility and longing.5. Evaluate how minor characters like Mrs. Cormaci contribute to the chapter’s themes.

Answer:

Mrs. Cormaci serves as both comic relief and a reminder of Gregor’s unresolved trauma. Her exaggerated complaints about heat and pushy tarot readings lighten the mood, but her probing questions about his father hint at deeper wounds Gregor avoids. Her intrusion into the apartment—drinking his root beer unasked—parallels how others impose on his life (e.g., caretaking duties). Yet her presence also offers respite, allowing Gregor brief escape to the laundry room. This duality reflects the chapter’s tension between communal support and the loss of personal autonomy in struggling families.

Quotes

1. “He ran his fingers over the bumps and resisted the impulse to let out a primal caveman scream. It was building up in his chest, that long gutteral howl reserved for real emergencies — like when you ran into a saber-toothed tiger without your club, or your fire went out during the Ice Age.”

This vivid description captures Gregor’s intense frustration and sense of entrapment, using powerful imagery to convey how overwhelming his mundane summer feels compared to prehistoric survival scenarios.

2. “‘I’m sorry, baby, you can’t go,’ his mother had told him a few weeks ago. And she really had been sorry, too, he could tell by the look on her face. ‘Someone has to watch Boots while I’m at work, and we both know your grandma can’t handle it anymore.’”

This exchange reveals the family’s financial struggles and caregiving burdens, showing how Gregor has prematurely taken on adult responsibilities since his father’s disappearance.

3. “So all Gregor had said was, ‘That’s okay, Mom. Camp’s for kids, anyway.’ He’d shrugged to show that, at eleven, he was past caring about things like camp. But somehow that had made her look sadder.”

This moment demonstrates Gregor’s forced maturity and self-sacrifice, where his attempt to appear grown-up only highlights how much childhood he’s missing.

4. “Sometimes Gregor was secretly glad that she could return to that farm in her mind. And a little envious. It wasn’t any fun sitting around their apartment all the time.”

This insight reveals Gregor’s complex feelings about his grandmother’s dementia - both compassionate and resentful - while emphasizing his own longing for escape.

5. “‘By September, I’ll probably be ecstatic when we get the phone bill.’”

This sarcastic internal thought perfectly encapsulates Gregor’s bleak outlook on his summer, where even mundane adult concerns seem preferable to his current boredom and isolation.