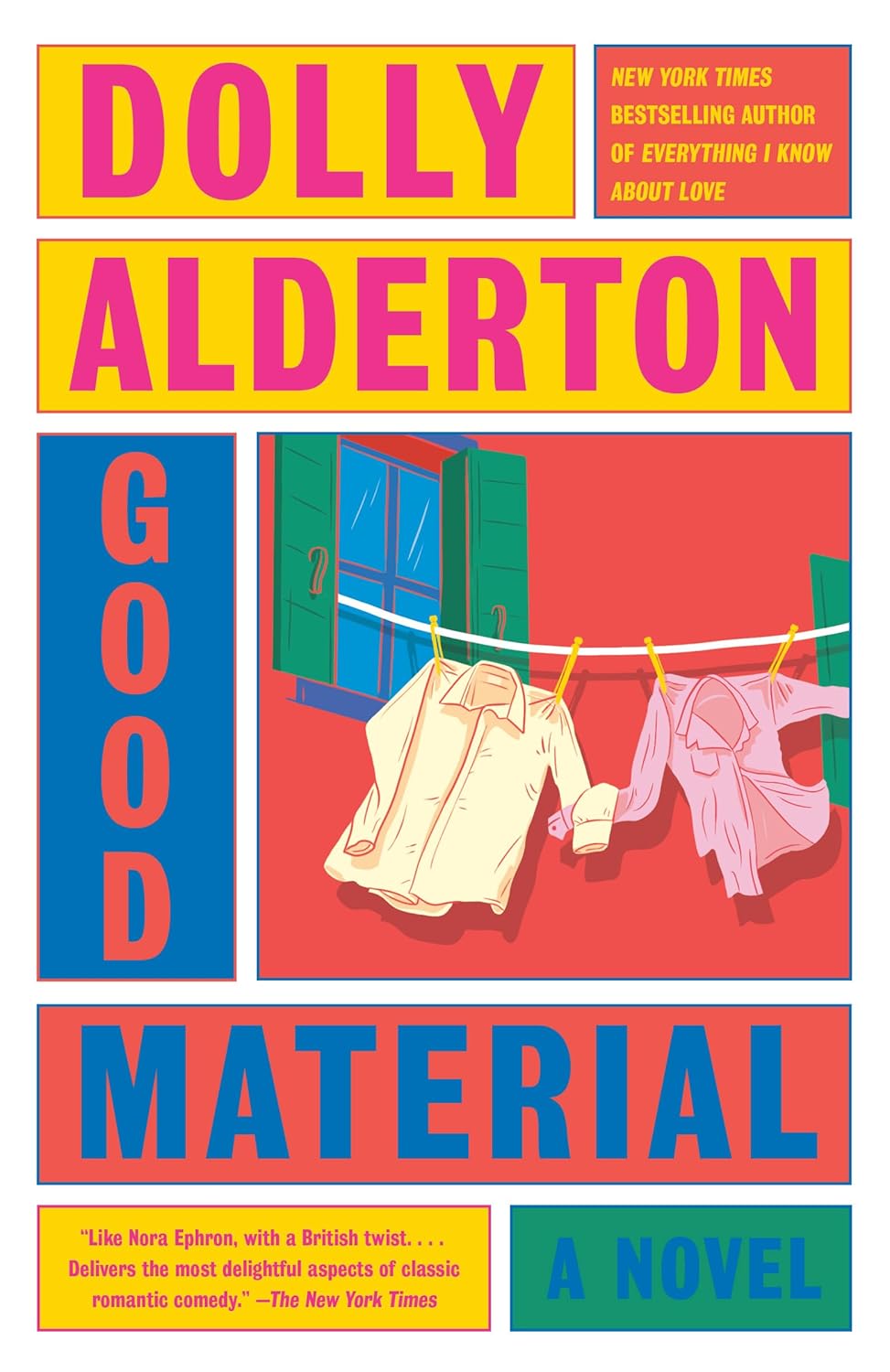

Good Material

Wednesday 18th September 2019

by Alderton, DollyThe chapter explores a unique experiment where the narrator, adopting the fictional identity “Clifford Beverley,” attends a therapy session to gain insight into his troubled relationship with his girlfriend, Alice. By posing as Clifford, he seeks professional advice on whether to end the relationship, reflecting his confusion and need for clarity. The narrator’s inventive approach stems from his desire to understand what a therapist might say about someone like him, influenced by imagined opinions that may have contributed to his breakup with Jen. This sets the tone for a candid exploration of personal doubts and relational dynamics.

During the session, Clifford reveals his concerns about the disparity between his corporate career as a lawyer and Alice’s unconventional, creative pursuits as a burlesque dancer and juggler. He expresses frustration and judgment towards Alice’s lifestyle, contrasting it with his own structured, financially driven path. The therapist probes deeper, challenging Clifford’s judgments and suggesting that his negative feelings might stem from deeper emotional conflicts rather than surface-level issues like income or job status. This dialogue highlights the complexity of Clifford’s feelings and the therapist’s attempt to unravel underlying causes.

The therapist encourages Clifford to reflect on his upbringing and parental influences, implying that his critical attitude towards Alice mirrors the judgments he experienced from his father. Clifford struggles to engage fully with this introspective line of inquiry, eager to focus on practical relationship concerns rather than childhood history. Despite his resistance, the session underscores the importance of addressing personal history to understand present relationship challenges. The therapist’s calm, methodical approach contrasts with Clifford’s impatience and skepticism about therapy’s value.

The chapter concludes with Clifford abruptly ending the session, feeling dissatisfied and skeptical about the therapeutic process. He is left grappling with unresolved questions about his relationship and his own emotional state. The narrative shifts briefly to his professional frustrations, as he notices delayed payments and a lack of career progress, adding to his sense of dissatisfaction. Overall, the chapter presents a nuanced portrayal of a man caught between conflicting desires, searching for answers through an unconventional and revealing therapeutic encounter.

FAQs

1. What motivates the narrator to create a fake therapy patient and attend a therapy session under this alias?

Answer:

The narrator invents a fake therapy patient named Clifford Beverley, combining his maternal grandfather’s name with his childhood pet’s name, to attend a therapy session anonymously. This is motivated by his desire to understand what a therapist might say about his relationship issues, specifically from the perspective of his girlfriend Jen’s therapist. He wants to gain insight into why Jen might have perceived him negatively and to explore whether he should break up with his girlfriend. Since he feels isolated with no one else to talk to and has exhausted other resources (“all my tokens are spent”), this unconventional approach is his attempt to find answers about his relationship.2. How does the therapist respond to Clifford’s initial judgmental attitude towards his girlfriend’s career choices, and what deeper issues does she try to explore?

Answer:

The therapist quickly notices Clifford’s judgmental stance towards his girlfriend Alice’s unconventional career as a burlesque dancer and juggler. Instead of accepting his surface-level criticism about her lack of a “proper job,” she probes deeper, suggesting his negativity may mask unresolved feelings, possibly linked to his upbringing and relationship with his father. She challenges Clifford to consider if his resentment is truly about her earnings or about the sexualized nature of her work. This approach encourages Clifford to reflect on his biases and the origins of his judgments, moving beyond simple critiques of career to examine personal and familial influences.3. In what ways does the therapy session highlight the contrast between Clifford’s expectations and the therapist’s approach to understanding his relationship?

Answer:

Clifford enters the therapy session seeking direct advice on whether to stay with Alice or break up with her in favor of a partner with a more conventional career. He wants clear judgments and solutions. However, the therapist resists giving simplistic answers or judgments, instead focusing on exploring Clifford’s own emotional patterns, family background, and deeper motivations. She redirects the conversation from Alice’s job to Clifford’s upbringing and internal conflicts, emphasizing that relationships and personal choices are complex and not about right or wrong paths. This contrast reveals Clifford’s frustration with therapy’s reflective process and his desire for straightforward conclusions.4. How does the narrator’s use of a fabricated identity and story during the therapy session affect the authenticity and potential outcomes of the session?

Answer:

By adopting a fabricated identity and inventing details about Clifford’s family and relationship, the narrator creates a layer of distance between himself and the therapy process. This can limit the authenticity of the session because the therapist is responding to a constructed narrative rather than the narrator’s real experiences and emotions. While this allows the narrator to safely explore certain themes indirectly, it also means that the therapist’s insights may not fully address his genuine issues. The invented story might prevent deeper breakthroughs, as the therapist’s questions about Clifford’s background are met with evasions or fabrications, reducing the potential for meaningful self-discovery.5. Reflecting on the narrator’s feelings at the end of the session, what does this reveal about his state of mind and his relationship with therapy?

Answer:

At the end of the session, the narrator feels frustrated and dismissive, thinking the therapy was a waste of money and expressing disbelief that Jen spends so much on similar sessions. This reaction reveals his skepticism about therapy’s value and his impatience with its indirect, exploratory approach. It also suggests a sense of desperation and unresolved conflict, as he is still searching for clear answers about his relationship but struggles with the ambiguous nature of therapeutic inquiry. His resentment towards the therapist and the financial cost underscores his conflicted attitude toward seeking help and his difficulty in confronting deeper emotional issues.

Quotes

1. “I had the idea while imagining all the things Jen’s therapist might have said about me which possibly contributed to our break-up and I thought: instead of all this solo theorizing, why don’t I find out what a therapist would say to someone like Jen going out with someone like me? I’ll imagine what Jen said about me and ask the therapist for advice.”

This quote sets up the chapter’s unique premise: the narrator’s attempt to understand a failed relationship by role-playing a therapy session under a false identity. It highlights his desire for insight and the unconventional method he chooses, framing the narrative’s exploration of judgment, relationships, and self-awareness.

2. “‘I’m only doing it because that’s what my dad did and I felt a lot of pressure to impress him. So when I met Alice, I found her job quite … brave. I admired her for doing something so different and not being traditional. But now I just want her to just … fucking … grow up.’ I say it with conviction that surprises even me.”

This passage reveals the narrator’s internal conflict and judgmental attitude toward his girlfriend’s unconventional career, while exposing his own insecurities and familial pressures. It captures a key emotional turning point where admiration turns to frustration, illustrating deeper themes of expectation and maturity.

3. “‘Sometimes we can disguise our real reasons for judgement with something we find easier to accept about ourselves. Are your negative feelings towards Alice’s job really about the fact she’s not earning enough money, or has it got anything to do with the fact that her job is, in a way, sexualized?’”

This quote from the therapist challenges the narrator to confront the root causes of his judgment. It introduces a critical psychological insight about disguised feelings and societal attitudes toward sex work, deepening the thematic complexity of the narrator’s struggle to understand both himself and his partner.

4. “‘What I think is interesting about what you just said is that you’re asking me to judge you just like your father judged you – just as you now judge Alice. But, what if it’s not always about the “right” or “wrong” way to do things, Clifford? What if it’s not about “you should do this” or “you shouldn’t do that”; what my role is as a therapist or Alice’s role is as a juggler,’ she says.”

This passage encapsulates the therapist’s main argument about the cycle of judgment and the need to move beyond rigid ideas of right and wrong. It represents a key thematic insight about acceptance and the complexity of human relationships, urging the narrator to reconsider his black-and-white thinking.

5. “I can’t believe Jen spends a hundred quid a week on this dross.”

This closing remark by the narrator conveys his skepticism and frustration with therapy and the process he has just undergone. It underscores his resistance to introspection and the difficulty of truly engaging with emotional complexity, reflecting the chapter’s tension between desire for answers and reluctance to face uncomfortable truths.