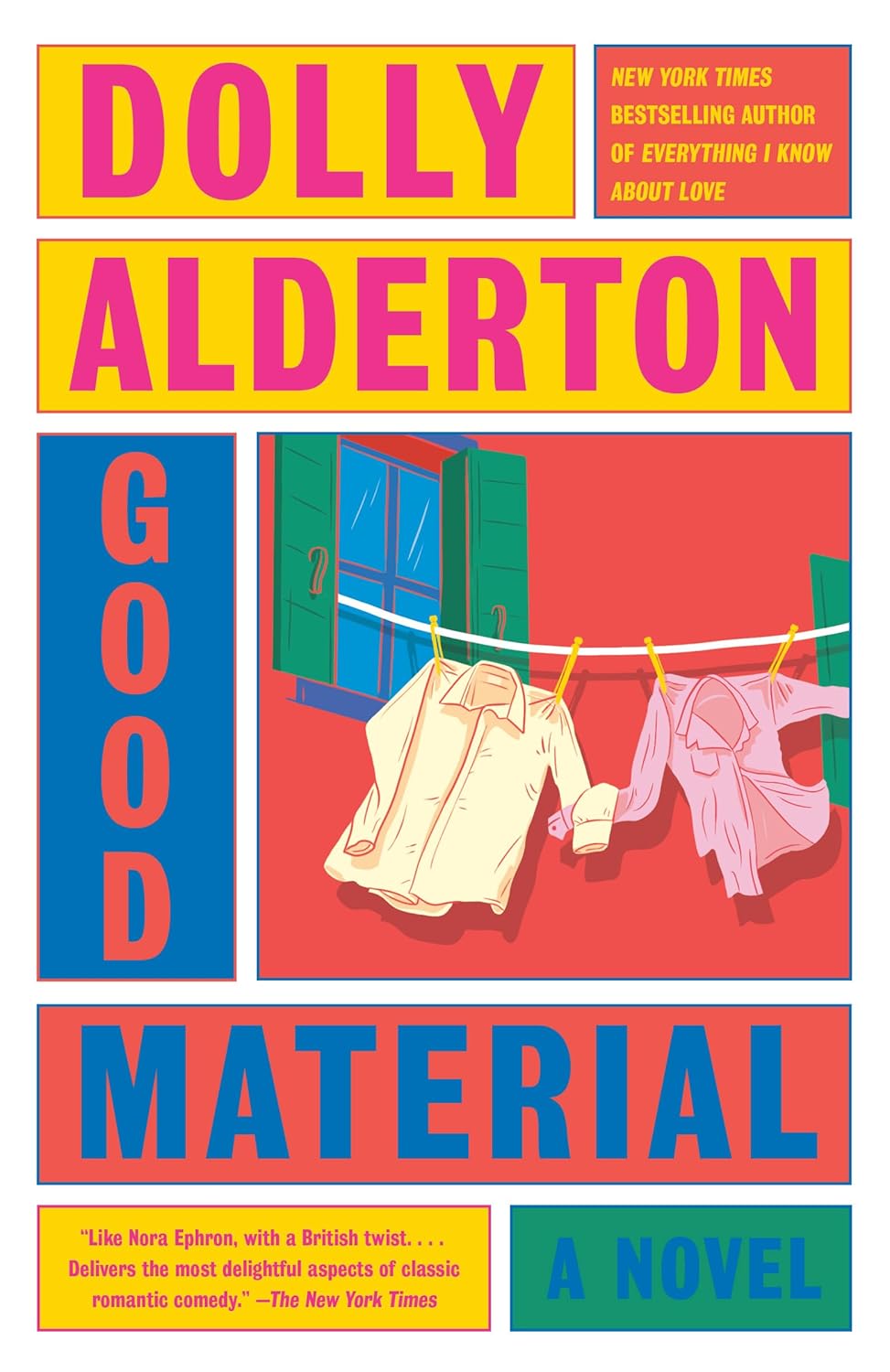

Good Material

Saturday 7th December 2019

by Alderton, DollyThe chapter opens with a vivid depiction of a bleak winter evening in suburban England, emphasizing the starkness and desolation of the environment. The narrator reflects on the short daylight hours and the dull, lifeless garden visible from their bedroom window, drawing a contrast between this mundane setting and more exotic, harsh landscapes. This somber atmosphere sets the tone for the narrator’s introspective mood as they engage in a quiet, yet emotionally charged interaction with their mother, who brings them tea and expresses concern about their infrequent visits, typically linked to times of distress.

As the evening progresses, the narrator contemplates the possibility of settling permanently in their hometown, weighing the simplicity and comfort of life with their mother against the complexities and isolations of life in London. They acknowledge the emotional and social distance from friends and significant others, highlighting their strained communications and the fading motivation that once fueled their fitness routines and healthy habits. The narrative conveys a sense of stagnation and longing for stability, juxtaposed with the pull of a life that feels both overwhelming and unfulfilling.

The shared dinner and television watching create a domestic backdrop for a deeper conversation about politics and dreams of a different life, such as owning a hotel abroad. The mother’s candid remarks and lighthearted fears about such a venture add warmth and humor, yet the narrator’s internal questioning about why they must return to London underscores a desire to avoid heartache and disappointment by embracing a quieter, more predictable existence. This tension between desire for safety and the necessity of confronting life’s challenges permeates the chapter.

The chapter culminates in a poignant moment when the mother, breaking her decade-long abstinence, smokes a cigarette in reaction to the distress over political outcomes, leading to a shared drink and an intimate conversation about rejection and emotional pain. The mother offers a profound insight into the nature of heartbreak, framing it as the resurfacing of all past rejections and insecurities. The narrator’s admission of exhaustion and difficulty in letting go deepens the emotional resonance, leaving the reader with a powerful reflection on vulnerability and the complexity of healing.

FAQs

1. How does the author use the description of the suburban garden to set the tone and atmosphere of the chapter?

Answer:

The author opens the chapter with a vivid, bleak description of the suburban garden in winter, emphasizing the early sunset, dull colors, and neglected objects like the garden gnome entangled in cobwebs and rain-filled jars once used as ashtrays. This imagery creates a somber, almost oppressive atmosphere that reflects the narrator’s internal state—feelings of stagnation, loneliness, and melancholy. The comparison to the Siberian desert ironically highlights the unexpected bleakness of this familiar English setting, reinforcing themes of isolation and emotional coldness that permeate the chapter.2. What does the conversation between the narrator and their mother reveal about their relationship and the narrator’s emotional state?

Answer:

The dialogue between the narrator and their mother reveals a complex, caring relationship marked by concern and subtle tension. The mother’s gesture of bringing tea and her comment about the narrator only coming home during heartbreak or Christmas indicate her worry and desire for closeness. The narrator’s defensiveness and eventual apology show vulnerability and a recognition of their emotional struggles. Their exchange about staying home more often hints at the narrator’s internal conflict about belonging and the possibility of stability versus their current transient, unsettled life. The mother’s supportive but honest presence highlights the narrator’s feelings of loneliness and search for comfort.3. How does the chapter explore the theme of heartbreak and emotional rejection?

Answer:

Heartbreak and emotional rejection are central themes explored through the narrator’s reflections and the mother’s insightful conversation. The narrator is grappling with the aftermath of a breakup, feeling exhausted and disconnected from their usual routines and social circle. The mother offers a profound perspective, explaining that getting dumped is not just about that one event but reactivates all past rejections—childhood bullying, parental absence, romantic disappointments, and workplace criticisms. This explanation deepens the understanding of emotional pain as cumulative and layered, suggesting that healing requires addressing these broader wounds, not just the immediate loss.4. In what ways does the narrator consider the idea of leaving London and what does this reveal about their current life situation?

Answer:

The narrator contemplates the possibility of staying permanently with their mother, stepping away from London’s fast-paced, demanding lifestyle. They imagine a quieter, simpler existence with familiar comforts—home-cooked meals, terrestrial TV, and reconnecting with old friends. This reflection reveals feelings of exhaustion, disillusionment, and a desire for emotional safety away from the complications of city life, social obligations, and past relationships. The narrator questions whether London is the root of their distress, indicating a desire to escape not just physically but emotionally from the pressures and heartbreaks associated with their current environment.5. How does the mother’s decision to smoke and drink brandy function symbolically in the chapter?

Answer:

The mother’s rare decision to smoke and drink brandy symbolizes the emotional weight of the political situation and her own stress, as well as a moment of vulnerability and honesty between her and the narrator. Her confession about secretly smoking since quitting highlights hidden struggles and the effort to protect the narrator from worry. This act breaks the usual boundaries of their relationship, signaling that both are affected by external pressures (like the election results) and internal emotional challenges. The brandy and cigarette become a catalyst for a deeper conversation about feelings, rejection, and support, marking a moment of connection and emotional revelation in the chapter.

Quotes

1. “I always forget how long this season feels, how little light or colour there is. I stare out of my bedroom window at Mum’s, watching dusk turn into night. I don’t think there’s a bleaker landscape than a garden of a suburban terraced house in England in the middle of winter.”

This opening reflection sets the somber, introspective tone of the chapter, emphasizing the emotional and physical bleakness that parallels the narrator’s internal state during this period of life transition.

2. “You only come home when it’s Christmas or you’re heartbroken. I don’t get many chances to make you tea.”

This exchange between mother and child poignantly captures the pattern of the narrator’s visits being tied to moments of emotional crisis, highlighting themes of family connection, care, and the narrator’s struggle with vulnerability.

3. “Maybe I should be here more. Maybe I should be here permanently… Perhaps London is the problem.”

Here, the narrator contemplates the possibility of choosing a simpler, quieter life closer to family over the chaotic pull of London, reflecting a critical internal debate about identity, belonging, and the cost of urban life.

4. “Getting dumped is never really about getting dumped… It’s about every rejection you’ve ever experienced in your entire life… When someone says they don’t want to be with you, you feel the pain of every single one of those times in life where you felt like you weren’t good enough. You live through all of it again.”

This profound insight from the mother reframes heartbreak as a cumulative experience of lifelong rejection, deepening the chapter’s emotional resonance and offering a universal perspective on personal pain and healing.

5. “I don’t know how to get over it, Mum… At this point I’m so tired of myself. I don’t know how to let go of her.”

The chapter closes on this vulnerable confession, encapsulating the narrator’s exhaustion and difficulty in moving on, which underscores the chapter’s exploration of emotional struggle and the search for resolution.