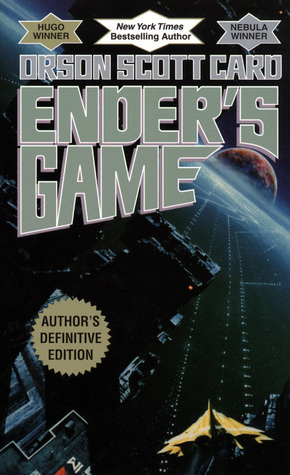

1986 — Orson Scott Card — Ender’s Game

Chapter 15: — Speaker for the Dead

by Game, Ender’sIn Chapter 15, “Speaker for the Dead,” Graff and Anderson converse on a tranquil lakeside dock, reflecting on Graff’s recent acquittal in a high-profile trial. Graff reveals his confidence in the outcome, attributing his victory to the unedited videos of Ender’s fights, which proved Ender acted in self-defense. The trial’s focus shifted to whether Ender could have won the war without Graff’s controversial training methods. Graff dismisses the ordeal, emphasizing the “exigencies of war” as justification. Anderson admits his initial doubts but expresses relief, revealing he offered to testify for Graff. Their dialogue underscores the moral complexities of Ender’s upbringing and the public’s volatile reactions.

Graff and Anderson discuss their future plans, with Graff contemplating retirement due to his accrued leave and savings. Anderson, however, prefers staying active, considering offers to lead universities or oversee sports leagues. Their banter reveals Graff’s weariness and Anderson’s restless energy. The conversation turns nostalgic when Graff mentions a raft built by Ender, hinting at the boy’s lingering presence. Anderson questions whether Ender will ever return to Earth, but Graff dismisses the possibility, citing Ender’s symbolic power as a tool for potential tyrants. Graff cryptically alludes to Demosthenes’ retirement and Locke’s role in keeping Ender away, suggesting deeper political machinations.

Ender, meanwhile, realizes he will not be returning to Earth despite his hopes. He watches his own trial by proxy, where his actions are scrutinized, and grapples with the irony of being celebrated for destroying the buggers while condemned for his human kills. Mazer Rackham consoles him, noting that historians will eventually distort his legacy. Ender feels the weight of his actions but remains detached, observing the hypocrisy of a society that glorifies wartime violence while vilifying personal survival. His friends depart for Earth, praising him in censored speeches, leaving Ender isolated on Eros as the colony efforts expand.

The chapter closes with Eros transforming into a hub for colonization, as humans prepare to inhabit the buggers’ abandoned worlds. Ender participates discreetly, his insights often ignored due to his age. He adapts by channeling ideas through sympathetic adults, demonstrating patience and strategic thinking even in peacetime. The narrative highlights Ender’s resilience and the bittersweet reality of his existence—a hero too dangerous to embrace, yet too valuable to discard. His story intertwines with humanity’s next chapter, as colonization offers a new beginning for both Ender and the species he saved.

FAQs

1. What were the main charges against Colonel Graff during his court martial, and how did he ultimately defend himself?

Answer:

Colonel Graff faced charges of mistreatment of children and negligent homicide related to Ender Wiggin’s training at Battle School and the deaths of Stilson and Bonzo. The prosecution used edited videos of Ender’s fights to portray Graff as irresponsible. However, Graff’s defense team showed the full videos, demonstrating that Ender acted in self-defense. Graff argued that his actions were necessary for humanity’s survival during wartime, and the court ultimately agreed that the prosecution failed to prove Ender would have succeeded without Graff’s methods. This “exigencies of war” defense secured his acquittal (Chapter 15).2. Why does Graff believe Ender Wiggin can never return to Earth, despite his hero status?

Answer:

Graff explains that Ender, though only 12 years old, is too politically dangerous to return. As the legendary “child-god” who saved humanity, Ender’s name holds immense power. Any aspiring tyrant could exploit him as a figurehead to rally armies or intimidate opponents. Even if Ender sought peace, factions would vie to control him. Graff reveals that Demosthenes (a political persona) recognized this threat and withdrew advocacy for Ender’s return. Locke, another political figure, argued to keep Ender on Eros precisely to prevent his manipulation by Earth’s power structures (Chapter 15).3. How does Ender’s perspective on his own actions differ from society’s view of him?

Answer:

While society celebrates Ender as a war hero, he privately grapples with guilt over all his actions—the deaths of Stilson, Bonzo, and especially the xenocide of the buggers. He notes the irony that killing two boys in self-defense is scrutinized, while exterminating an entire alien species (who had ceased hostilities) is glorified. Ender feels the weight of all these deaths equally, seeing them as interconnected crimes rather than separate justified and unjustified acts. This internal conflict contrasts sharply with the public’s selective reverence (Chapter 15).4. What strategic role does Graff take on after his acquittal, and how does it connect to broader themes in the chapter?

Answer:

Graff becomes Minister of Colonization, overseeing human expansion to the former bugger worlds. This role reflects the chapter’s themes of transition from war to reconstruction and the cyclical nature of human ambition. Graff notes that people will always seek new frontiers, just as they once sought victory in war. His position also symbolizes the practical consequences of Ender’s victory—the buggers’ empty planets become humanity’s new “game board,” replacing military conflict with colonial expansion (Chapter 15).5. Analyze how Ender demonstrates political acumen despite being sidelined by adult bureaucrats.

Answer:

Though ignored as a child, Ender adapts by channeling ideas through sympathetic adults who present them as their own—a subtle manipulation mirroring his battle strategies. He also observes the Graff trial keenly, recognizing how his reputation is both weaponized and protected by factions. This shows his growing understanding of power dynamics. His reflection on the buggers’ fate (“no one thinks to call it a crime”) further reveals his ability to critique systemic hypocrisy—a skill that foreshadows his future role as Speaker for the Dead (Chapter 15).

Quotes

1. “I said I did what I believed was necessary for the preservation of the human race, and it worked; we got the judges to agree that the prosecution had to prove beyond doubt that Ender would have won the war without the training we gave him. After that, it was simple. The exigencies of war.”

This quote from Graff encapsulates the moral justification for Ender’s brutal training—the ends (saving humanity) justified the means. It highlights the chapter’s exploration of moral ambiguity in wartime decisions.

2. “In all the world, the name of Ender is one to conjure with. The child-god, the miracle worker, with life and death in his hands.”

Graff explains why Ender can never return to Earth—he’s become a symbolic figure too powerful for any faction to control. This reveals the central irony of Ender’s victory: saving humanity has made him a political threat.

3. “In battle I killed ten billion buggers, who were as alive and wise as any man, who had not even launched a third attack against us, and no one thinks to call it a crime.”

Ender’s internal reflection contrasts society’s focus on his schoolyard fights with their indifference to xenocide. This profound statement captures the chapter’s meditation on moral perspective and the weight of Ender’s unintended genocide.

4. “People always go. Always. They always believe they can make a better life than in the old world.”

Graff’s observation about human colonization patterns foreshadows the series’ future while commenting on humanity’s restless nature. This simple statement carries deep thematic weight about human ambition and expansion.

5. “But he was patient with their tendency to ignore him, and learned to make his proposals and suggest his plans through the few adults who listened to him, and let them present them as their own.”

This shows Ender’s maturation into a different kind of leadership—working behind the scenes rather than commanding openly. It marks a key transition in his character development post-war.