Chapter 8: Department of Easy Virtue

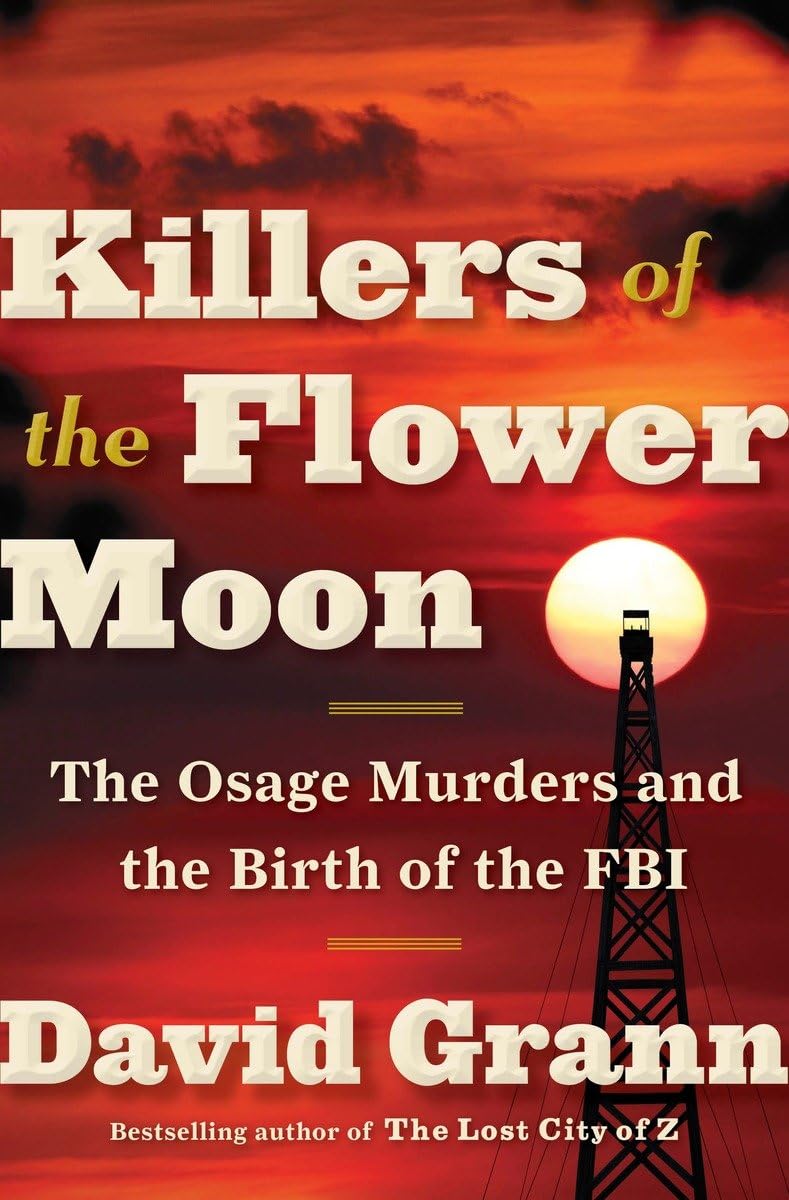

byIn the summer of 1925, Tom White, a veteran special agent of the Bureau of Investigation, received an urgent summons from J. Edgar Hoover, the Bureau’s newly appointed director, to meet in Washington, D.C.. At the time, Hoover was in the midst of overhauling the Bureau, which had become synonymous with corruption and inefficiency, earning the scornful nickname “the Department of Easy Virtue.” White, a former Texas Ranger whose law enforcement career was rooted in the traditions of frontier justice, was a man of principle and discipline, yet his rugged, independent methods stood in contrast to Hoover’s vision for a highly regimented, modernized agency.

Unlike Hoover, who was determined to create a centralized, data-driven Bureau, White embodied the old-school approach to policing—relying on intuition, face-to-face investigations, and fieldwork rather than bureaucratic oversight. He had built his reputation through dogged perseverance, fearlessness, and an unwavering commitment to justice, qualities that had earned him a reputation as one of the most reliable lawmen of his time. However, his career had evolved alongside the shifting landscape of American law enforcement, moving from the days of horseback pursuits and shootouts to an era where scientific methods and structured legal frameworks were beginning to redefine the field.

Hoover, aware of the mounting criticism of his leadership and the Bureau’s inability to solve major cases, needed someone like White—a lawman with an untainted reputation and a proven ability to navigate complex cases. The Bureau had failed to bring justice in the Osage murders, a case that had become an embarrassment to federal law enforcement, exposing glaring weaknesses in investigative practices and raising concerns of corruption within the government itself. The Osage people, victims of a systematic campaign of murder and exploitation, had waited years for answers, yet law enforcement had failed them at every turn, allowing the perpetrators to continue killing with impunity.

Upon his arrival in Washington, White found himself stepping into an environment drastically different from the one he was accustomed to. While he was used to tracking fugitives in the harsh Texas terrain, Hoover’s Bureau operated from behind desks, through files, and with strict procedural oversight—a stark contrast to White’s direct, hands-on approach to law enforcement. Hoover, keenly aware that his own career hinged on proving the Bureau’s effectiveness, made it clear that the Osage case was not just another murder investigation, but a defining test of the Bureau’s credibility under his leadership.

Despite White’s deep respect for traditional law enforcement methods, he recognized the value in Hoover’s push for modernization, particularly when it came to standardizing investigative procedures and improving forensic capabilities. His past work, particularly his undercover mission as a warden in the Atlanta penitentiary, had demonstrated his ability to adapt to complex, high-stakes environments, making him the ideal candidate for Hoover’s mission. His task was simple in concept but daunting in execution—bring the Osage murderers to justice and restore faith in the Bureau of Investigation.

The Osage murder investigation was far more than a case—it was a battle against deeply entrenched corruption, racial prejudice, and powerful men who had spent years profiting off the deaths of innocent people. White, unlike previous investigators who had been ineffective or compromised, was determined to piece together an airtight case, build an unbroken chain of evidence, and expose the criminals operating in Osage County. Yet, he knew that his biggest challenge wouldn’t just be catching the killers—it would be navigating a system designed to protect them.

As he took on his most difficult assignment yet, White understood that his methods would be tested like never before. The collision between the old ways of law enforcement and Hoover’s new vision for the Bureau would define not only his career but also the future of federal investigations in America. In many ways, the Osage case wasn’t just about solving a string of murders—it was about proving that justice could still prevail, even in the face of greed, deception, and institutional failure.