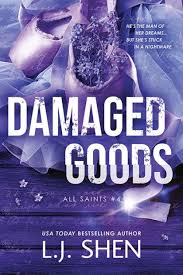

CHAPTER I — Damaged Goods

byChapter I begins with George Dupont leaving a house just before sunrise, his steps slowed not by fatigue but by the weight of guilt that clings to his conscience. Though engaged to Henriette, a woman admired for her virtue and grace, George carries the secret of a recent betrayal—an encounter that now threatens to dismantle the foundation of their relationship. The stillness of the Paris morning offers no comfort; instead, it amplifies the noise of regret in his mind. His past with Lizette, a girl of lower status and genuine affection, resurfaces in memory, blurring the lines between convenience, desire, and consequence. George reflects on how social expectations have often justified indulgences among men of his class, yet this time, the personal cost feels heavier. He cannot dismiss the possibility of having contracted a disease, a fear that mixes shame with dread and sets the tone for the burden he must carry into his future.

While his social circle would dismiss such indiscretions as harmless affairs, George begins to question the very code that shaped his choices. The tension between outward respectability and hidden transgressions forms the backbone of his internal struggle. He recalls the lectures from his elders about securing a respectable marriage and the whispered jokes among peers about temporary pleasures before settling down. Yet, none of those words prepared him for the cold fear now anchored in his gut—a tiny lesion on his lip that could symbolize something far more serious than guilt. That single blemish transforms from a minor annoyance into a looming symbol of a moral debt. George is not only afraid of losing Henriette but of being exposed, judged, and possibly punished by the very society that once encouraged his indiscretions. This contradiction, the space between permissiveness and accountability, forces George to rethink what it means to be a man of honor.

His thoughts spiral as he imagines the consequences not just for himself, but for Henriette and their unborn future. Marriage, once an escape from disorder, now seems like a dangerous trap if entered without disclosure. He begins to consider visiting a doctor—not for a cure, but perhaps for validation, hoping the worst can still be avoided. But even this step feels fraught with shame. Public health campaigns are beginning to spread awareness, but stigma still chokes the conversation around sexually transmitted diseases. Men like George, raised with privilege and pride, often find themselves too proud to seek help until it’s too late. In this regard, George’s dilemma represents more than a personal failing; it mirrors a cultural silence that allows ignorance to thrive in shadows. The fear of being labeled, the fear of facing Henriette’s disgust, outweighs his instinct to confess or act responsibly. Instead, he delays—an all-too-common reaction driven by fear, not malice.

The story subtly critiques the societal construct of “mariage de convenance”—arranged unions based more on compatibility of status than love or transparency. George’s engagement to Henriette, though romanticized in society’s eyes, rests on a fragile foundation. It’s a match crafted with social optics in mind, one that expects virtue from women and discretion from men. As George’s conscience swells with dread, his mind returns to Lizette, not just as a person but as a representation of choices made without foresight. Her existence outside his circle afforded him freedom, but also recklessness. The unspoken class divide allowed his actions to remain hidden—until now. Lizette had been discarded, but her memory lingers like the physical symptom George fears is growing worse each day.

Throughout this chapter, the theme of duality is ever-present: appearances versus truth, love versus lust, health versus decay. George’s suffering is not just physical; it’s spiritual, cultural, and existential. The dawn that should bring light and renewal only exposes the darkness of his choices. He is not yet ready to confront his mistake openly, but something within him shifts as the sun rises. A man who once viewed illness as a concern for others now sees himself as a possible carrier, both of disease and of shame. The weight of this realization begins to change him, quietly but irrevocably. The journey ahead, though still clouded by uncertainty, has begun with the first pangs of guilt—a necessary seed for transformation.